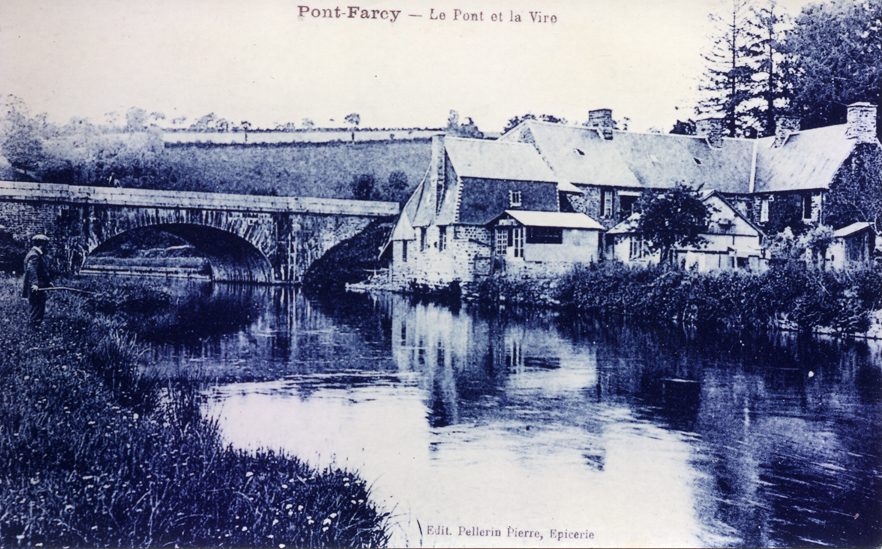

Pont-Farcy, Calvados, France

A small town by a bridge in Normandy

By Christopher Long

Pont-Farcy's origins

Pont-Farcy's origins

P

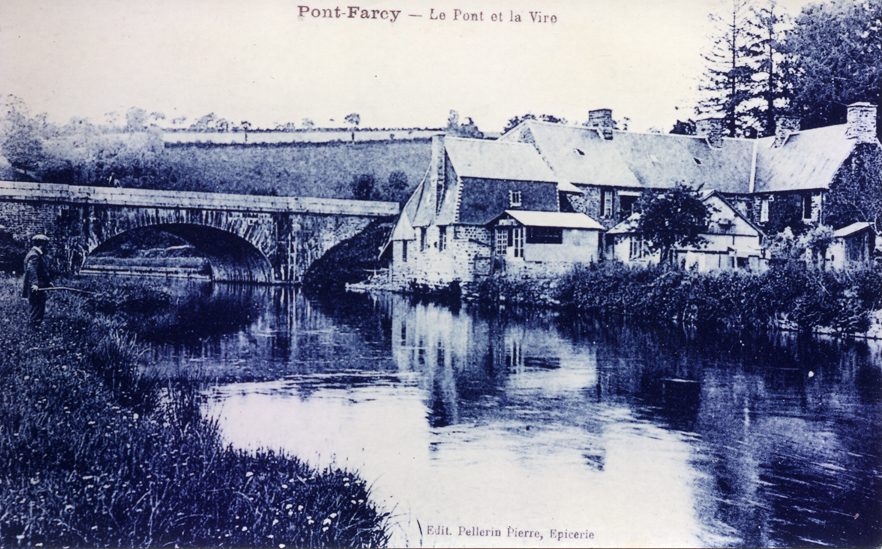

ont-Farcy came into existence because long ago it stood on the site of one of the most important crossing places on the river Vire. A stone bridge built by the Farcy family in the early C13th gave the town its modern name, but there may well have been an important bridge or ford long before this.

In mediaeval times the river Vire was the only major obstacle for people travelling along the ancient ridgeway roads linking great cities like Caen and Bayeux with the Breton frontier near Avranches and Mont Saint-Michel.

For about 15 kilometres the river Vire cuts its way through a hillside of ancient Cambrian rock, forming a series of dramatic and almost inaccessible gorges.

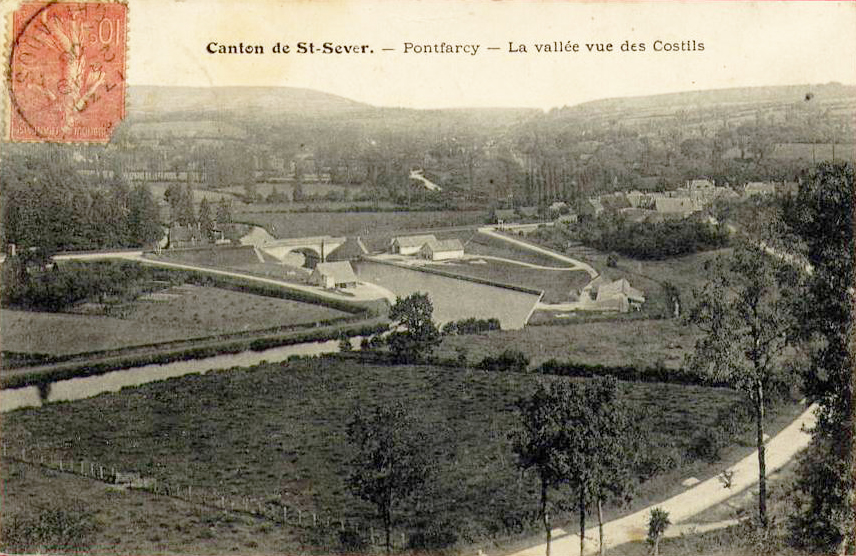

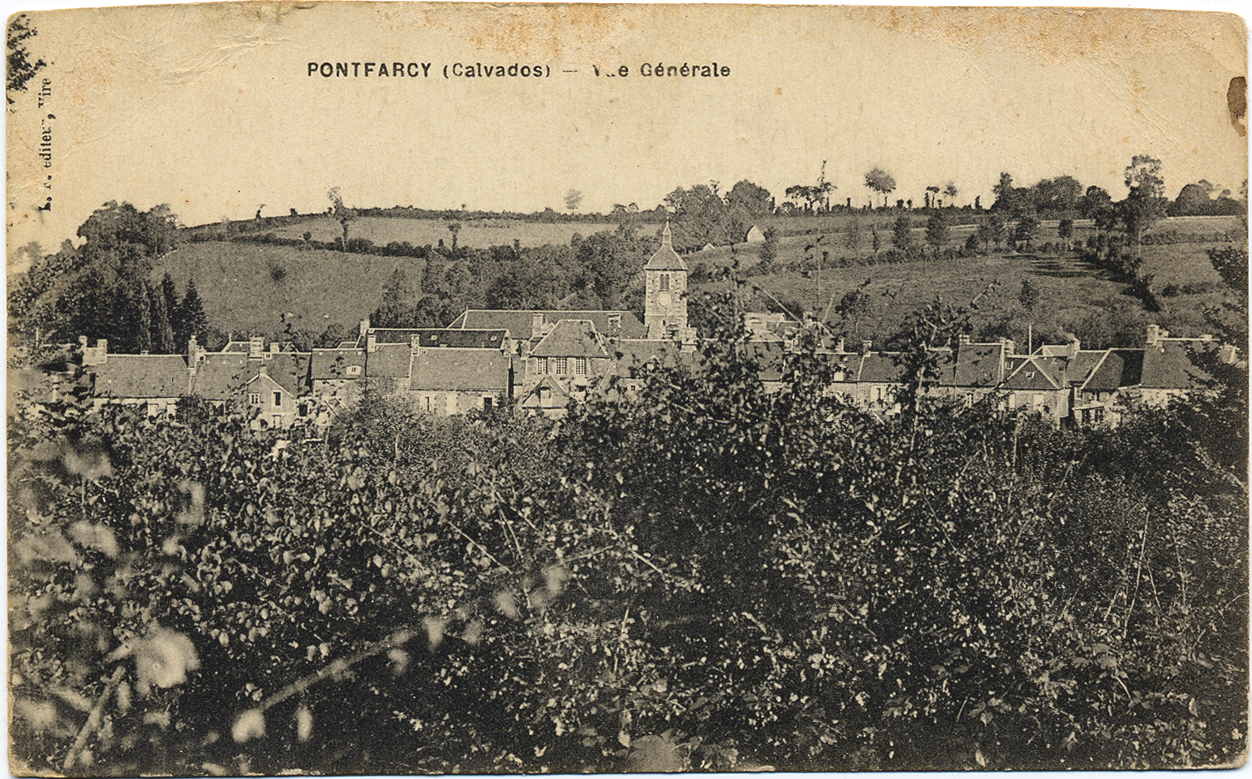

Then, at Pont-Farcy, the terrain at last offers an accessible and solid footing on both banks – the perfect setting for a bridge and a firm foundation for the small, compact bourg which sits on a rocky outcrop.

At its lowest point, beside the old canal port, the commune is only 39 metres above sea level, but to the west it soars to 253 metres with 20 kilometre views in all directions over the delightful hills, wooded valleys and streams of the bocage virois.

At its lowest point, beside the old canal port, the commune is only 39 metres above sea level, but to the west it soars to 253 metres with 20 kilometre views in all directions over the delightful hills, wooded valleys and streams of the bocage virois.

For centuries, Pont-Farcy's crossing point provided travellers with a safe place to rest or spend the night. Then, in the 1960s, a new bridge and a by-pass were built, leading to the closure of most of the town's shops and businesses. By 2001, a motorway and yet another new bridge meant that passing trade disappeared completely.

Dominique Doublet has published remarkable research now lodged with the Archives Départementales in St Lô revealing that, before the Farcy family gave their name to their bridge, there was a church and parish here called St Jean de Mesnil-Guérin which bordered a neighbouring parish named Ste Marie de Mesnil-Guérin – today, Ste Marie-Outre-L'Eau. The Farcy (Farsi) owned the land possibly as early as the C11th.

Dominique Doublet has published remarkable research now lodged with the Archives Départementales in St Lô revealing that, before the Farcy family gave their name to their bridge, there was a church and parish here called St Jean de Mesnil-Guérin which bordered a neighbouring parish named Ste Marie de Mesnil-Guérin – today, Ste Marie-Outre-L'Eau. The Farcy (Farsi) owned the land possibly as early as the C11th.

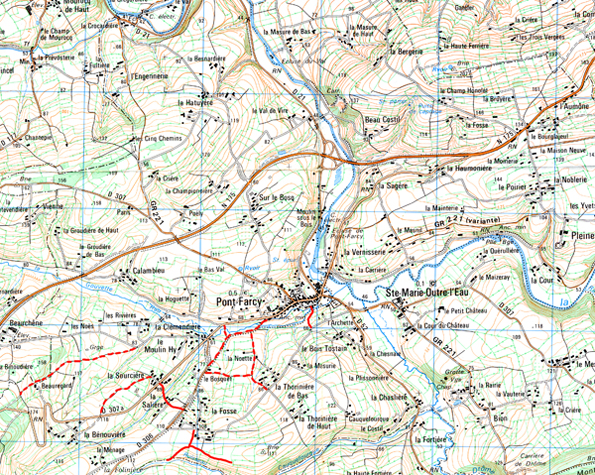

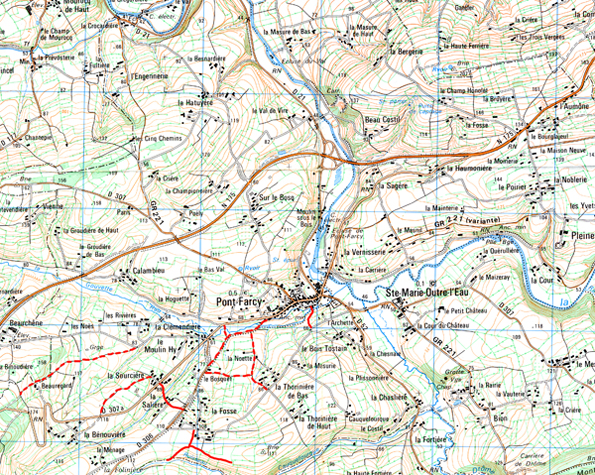

Right: Detail from the Mariette de la Pagerie map published very early in the C18th.

The town did not acquire its present name until the C13th when the seigneur of that time, a member of the Farcy family, built a stone bridge, charged a toll to those who used it and gave his name to the parish in which it stood. The bridge is likely to have replaced a ford with some form of 'clapper' bridge or stepping-stones for pedestrians. The lords of Mesnil-Guérin had received or obtained by marriage (ca. 1140) part of the neighbouring Soligny barony of Guilberville (including Sédouy, Chapelle-Heuzebroc, part of Beuvrigny and St Louet-sur-Vire, etc). It is interesting that 'Guérin' appears in connection with the manors at Le Mesnil-Ceron and at Le Chêne Guérin and the 'carrefour Guérin' (Pont-Farcy).

According to Anglo-French sources, including mediaeval documents in the Tower of London – (see Stapleton and Doublet) – the Mesnil-Guérin family followed William the Conqueror to England where their name was transformed into the well-known English surname 'Mainwaring'. Soon after, in the early C14th, the lordship of the manor of Pont-Farcy passed by marriage from a Farcy to a Carbonnel and then to a succession of others.

According to Anglo-French sources, including mediaeval documents in the Tower of London – (see Stapleton and Doublet) – the Mesnil-Guérin family followed William the Conqueror to England where their name was transformed into the well-known English surname 'Mainwaring'. Soon after, in the early C14th, the lordship of the manor of Pont-Farcy passed by marriage from a Farcy to a Carbonnel and then to a succession of others.

Right: Detail from a map based on the Carte de Cassini published in the late C18th.

Among the subsequent lords of the manor were: Richard Carbonnel mentioned 1332, Henri de Carbonnel mentioned 1456 and also seigneur of Brévant and Saint-Denis-le-Gast, a de Formentières mentioned early C16th, Jacques de Pontbellanger mentioned 1574, Gilles de Gouvets mentioned 1599, René de Sainte-Marie who bought the fiefdom of Pont-Farcy in 1647, Anne de Pontbellanger widow of Jacques Maillard, Jacques d'Amphernet, et Jacques du Quesnay mentioned 1758.

Some of these local seigneurs were among the many local protestants who built and funded a reformed church at Chêne Guérin, near Gouvets, the walls of which still stand today. According to D. Doublet, in the C12th, Chêne Guérin was held by the same Guérin family which held Pont-Farcy.

It is not known whether any of these lords maintained a manor house or seigneurie within the parish itself. There does not appear to be any surviving physical evidence of this. On the other hand there's reason to believe that there was more populous and significant settlement at La Hatuyère – la Haute Tuyère – on a dominant hilltop overlooking the town and the bridge. On the other hand the Guérin family appear to have left a trace of their presence at the 'Guérin' cross-roads, marked on the 1832 Napoleonic map, close to the modern water reservoir to the west of Les Hauts Vents on the Route de Montabot.

It is not known whether any of these lords maintained a manor house or seigneurie within the parish itself. There does not appear to be any surviving physical evidence of this. On the other hand there's reason to believe that there was more populous and significant settlement at La Hatuyère – la Haute Tuyère – on a dominant hilltop overlooking the town and the bridge. On the other hand the Guérin family appear to have left a trace of their presence at the 'Guérin' cross-roads, marked on the 1832 Napoleonic map, close to the modern water reservoir to the west of Les Hauts Vents on the Route de Montabot.

There are about 15 kms of often spectacular gorges between Ste-Marie-Laumont and Pont-Farcy which continue briefly around Les Roches de Ham.

Almost certainly such a seigneurie existed in neighbouring Ste-Marie-Outre-L'Eau, giving rise to the lieu-dit 'La Cour'. In this case, the author suggests, the building probably sat on the raised platform of land due south of the church's south door and adjacent to old stone farm buildings now converted to a gîte. The site of the original château is now partially covered by modern farm buildings, but the flat platform on which it once stood is still visible beside the road. On the opposite side of the road, the château's original home farm have survived, along with farm's name, about 100 metres to the west at Le Vieux Château or La Cour du Château. Significantly, Pont-Farcy offers no equivalent seigneurial toponyms or lieux-dit.

The author suggests that an original mediaeval main road through Pont-Farcy was the lane known today today as Le Bas du Bourg. This still exists, little changed by the centuries, running from Pont-Farcy's bridge, through what became for many years the bakery and continues parallel with the Archette stream, as far as the Moulin Sous Le Bourg where it turns north, across the present-day high-street to become the Route de Montabot – the start of one of several ancient ridgeway roads in the vicinity. Another lane may have run from the Moulin Sous Le Bourg, beside the mill leet, as far as Le Vivier where, as the name suggests, there would once have been a pool stocked with fish. In the days before the construction of the C19th main road from Pont-Farcy to Villedieu, this lane may even have continued as far as Le Moulin Hy. Unfortunately the construction of the C19th main road (D675, Pont-Farcy to Villedieu) will have obliterated much evidence of older lanes nearby.

The author suggests that an original mediaeval main road through Pont-Farcy was the lane known today today as Le Bas du Bourg. This still exists, little changed by the centuries, running from Pont-Farcy's bridge, through what became for many years the bakery and continues parallel with the Archette stream, as far as the Moulin Sous Le Bourg where it turns north, across the present-day high-street to become the Route de Montabot – the start of one of several ancient ridgeway roads in the vicinity. Another lane may have run from the Moulin Sous Le Bourg, beside the mill leet, as far as Le Vivier where, as the name suggests, there would once have been a pool stocked with fish. In the days before the construction of the C19th main road from Pont-Farcy to Villedieu, this lane may even have continued as far as Le Moulin Hy. Unfortunately the construction of the C19th main road (D675, Pont-Farcy to Villedieu) will have obliterated much evidence of older lanes nearby.

Before the creation of the mid-C19th D675, the road to Villedieu was much more picturesque. Your cart drove up the high street and down the small lane to Le Vivier before running across the water meadows and two fords: one fording the mill leet and the other fording the Gouvette stream. The road then followed the parish boundary and a deep sunken lane as far as the two hamlets Le Bosquet and Le Boquet on the Route de Montbray. You probably stopped for a drink in Montbray and again in Beslon before travelling on to Villedieu. Most of these old roads still exist. But the sunken road in Pont-Farcy was filled with the town's refuse in the 1950s and 1960s and to this day the public right of way remains, shamefully, blocked...

Geographically the commune is far smaller (13.45 sq km) than most of its neighbours which may be significant if the history of the former parish is to be understood. Sitting conveniently halfway between Caen and Mont-Saint-Michel, as well as halfway between St Lô and Vire, Pont-Farcy was a commune where passing trade and commerce may have earned more wealth than agriculture.

Geographically the commune is far smaller (13.45 sq km) than most of its neighbours which may be significant if the history of the former parish is to be understood. Sitting conveniently halfway between Caen and Mont-Saint-Michel, as well as halfway between St Lô and Vire, Pont-Farcy was a commune where passing trade and commerce may have earned more wealth than agriculture.

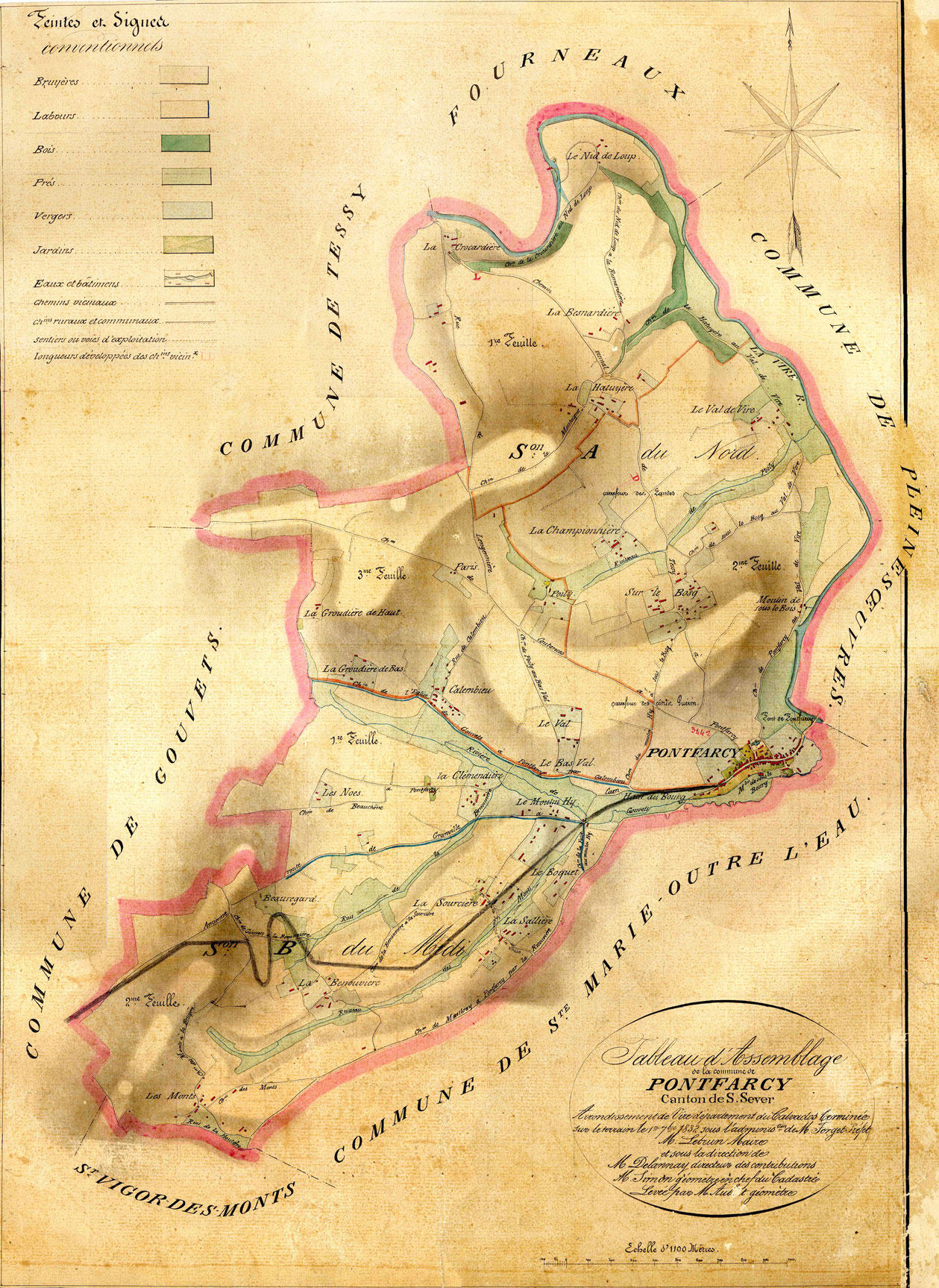

Pont-Farcy's 'Napoleonic' cadastre was published in 1832. However, soon after, a new main road (today's D675) from Pont-Farcy to Villedieu was built, cutting a swathe through the countryside. Someone has pencilled in the new road in the map right, but click on the image to see the original.

The fact that we know so little about Pont-Farcy's history before the C17th suggests that there may not really have been all that much to know until the 'modern' late-C17th or early-C18th high street we know today was built. But Pont-Farcy's commercial life must have really taken off when a new road sliced its way down from St Martin-des-Besaces, crossed Pont-Farcy's stone bridge and up the high street we know today, before disappearing upwards and westwards towards Villedieu, Avranches and Brittany. This explains why parishes such as Saint-Louët, Beuvrigny, Pleines-Oeuvres, Gouvets and St Vigor-des-Monts never evolved into commercial towns. They were, quite simply, by-passed by the new straight road which brought prosperity to Pont-Farcy for three centuries until it too was a victim of a new by-pass.

By the mid-19th century the population stood at over 1,000, falling slowly thereafter, partly owing to war casualties and partly to the growth in dairy farming which was less labour intensive than arable farming. But the greatest cause of the reduced population must have been the improved work opportunities in industrial towns like Vire.

By the mid-19th century the population stood at over 1,000, falling slowly thereafter, partly owing to war casualties and partly to the growth in dairy farming which was less labour intensive than arable farming. But the greatest cause of the reduced population must have been the improved work opportunities in industrial towns like Vire.

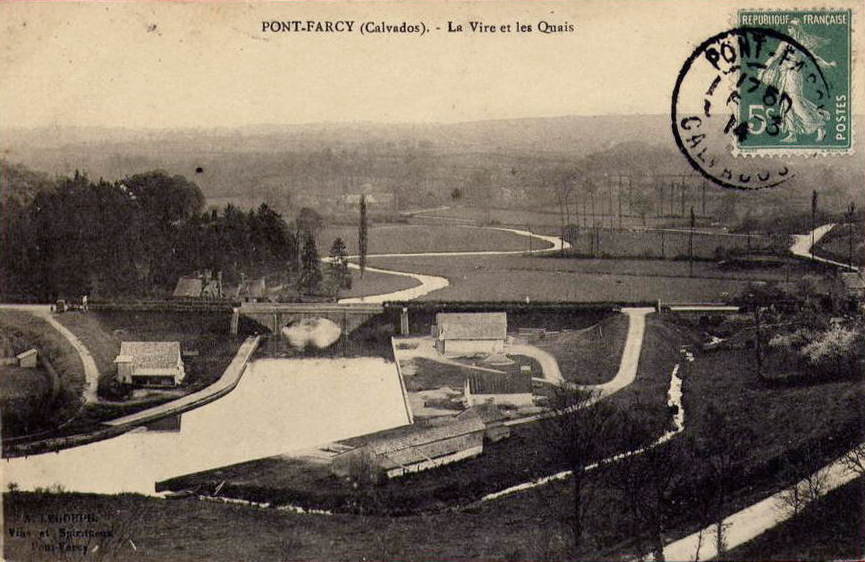

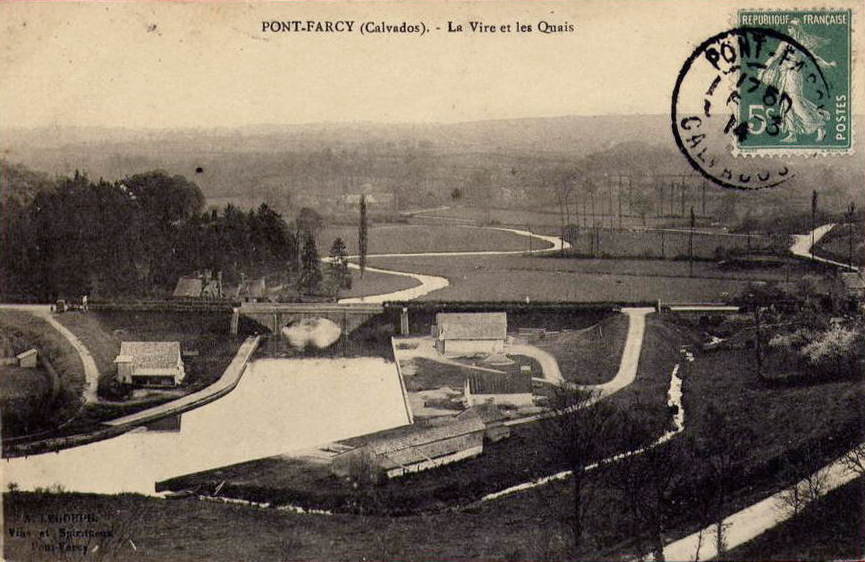

For a few years after 1861 Pont-Farcy considered itself an important 'port' town at the head of the newly built Vire Canal, but the town soon discovered that its nearest neighbour, Tessy-sur-Vire, had won the game. The railways arrived soon after the canals, offering ever greater speed, efficiency and value for money. Tessy became a railway town with important goods yards for freight handling that would eventually kill off the Vire canal and Pont-Farcy's port. But in the 1930s Tessy too became a victim when the flexibility of road transport made the railway redundant. Pont-Farcy could briefly enjoy its position on the main road again.

During the second half of the C20th there was a catastrophic drop in Pont-Farcy's population down to 487 in 1990, largely as a consequence of a new concrete bridge and a by-pass which removed the passing trade and led to the death of most of the town's remaining shops and small businesses. Property prices plummeted and about a quarter of the commune's old rural habitations were vacant, abandoned or in ruins.

During the second half of the C20th there was a catastrophic drop in Pont-Farcy's population down to 487 in 1990, largely as a consequence of a new concrete bridge and a by-pass which removed the passing trade and led to the death of most of the town's remaining shops and small businesses. Property prices plummeted and about a quarter of the commune's old rural habitations were vacant, abandoned or in ruins.

In the early years of the C21st numbers began to rise again, helped by a small influx of English settlers, but mostly due to the arrival of young French families, helped by easier access to bank loans, who bought new houses or renovated old ones, all within commuting distance of their work in Caen, St Lô or Vire.

Other crossing places (bridges or fords) on the river included Étouvy, Campeaux, Pont-Bellhanger, Tessy and St Lô and Vire itself.

The church of St Jean

W

e know that around the time of the Norman Conquest there was parish with a church dedicated to St Jean the Baptist de Mesnil-Guérin and that this parish almost certainly became known as Pont-Farcy when new lords of the manor, the Farcy family, built a stone bridge and gave their name to it. These 'lords' – or seigneurs – had the feudal right to appoint their clergy.

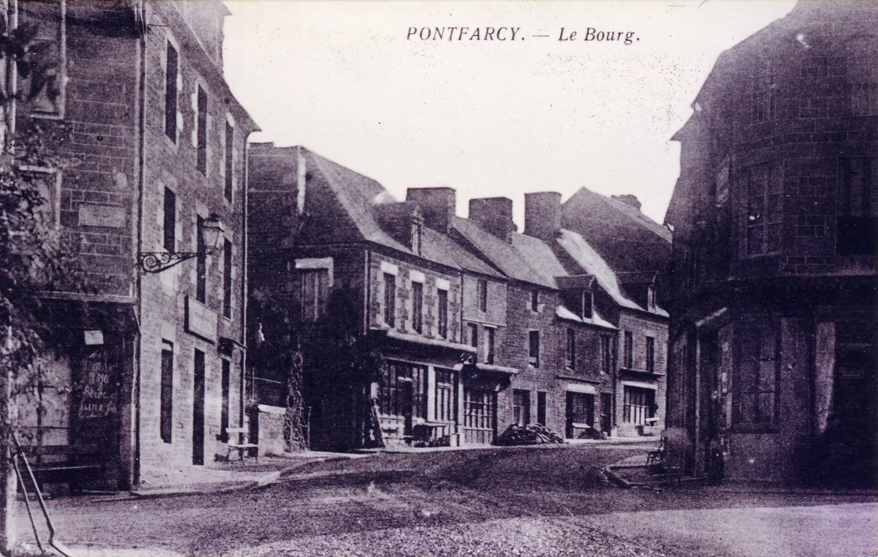

The pictures of Pont-Farcy church above and below, taken in 1921 and 2007, show that the clock face was raised at some stage. This presumably coincided with electrification after 1936 when the magnificent 1910 mechanism was made redundant. And since this postcard dates from 1912 (before WWl) there is, of course, no monument aux morts...

The foundations of this mediaeval church must lie beneath the largely late-C17th church we know today. The original church had a typically Norman crossing tower and, according to Arcisse de Caumont, who visited the church before a major re-modelling in the late-C19th, the building had 'gothic' trefoil bays and no windows in its north wall.

The foundations of this mediaeval church must lie beneath the largely late-C17th church we know today. The original church had a typically Norman crossing tower and, according to Arcisse de Caumont, who visited the church before a major re-modelling in the late-C19th, the building had 'gothic' trefoil bays and no windows in its north wall.

Pictured right, in the 'new' porch at the foot of the C17th tower, are some surviving remains of what may have been the 'old' porch leading into the mediaeval church. Today the present porch also displays the magnificent but now redundant church clock which was given to the commune in 1910 by Mlle Joséphine Hurel who had died the year before.

In the 1680s the old tower was demolished and replaced by the present west-end tower. Following the building of the sacristy and widespread re-modelling in the late-C17th, probably the only decorative vestiges of the original building may those visible in the interior wall at the base of the present tower which may be the remains of an original west-door porch see above right.

In the 1680s the old tower was demolished and replaced by the present west-end tower. Following the building of the sacristy and widespread re-modelling in the late-C17th, probably the only decorative vestiges of the original building may those visible in the interior wall at the base of the present tower which may be the remains of an original west-door porch see above right.

It's possible too that the honey-coloured 'surface granite' around the south door in the 'new' tower is re-used stone from the mediaeval church.

In the author's opinion, the awkward shape and proportions of the stonework around this 'gothic' doorway may be the consequence of a mason reworking old stone from an original roman arch. If so, this could explain the inconsistent colour of the granite facade which combines honey-coloured 'surface granite' around the doorway, with grey 'Vire' granite, in the coins.

The date above this door, 1745, records a later remodelling of this 'new' facade while a further more comprehensive re-modelling of the walls and windows took place in the late C19th.

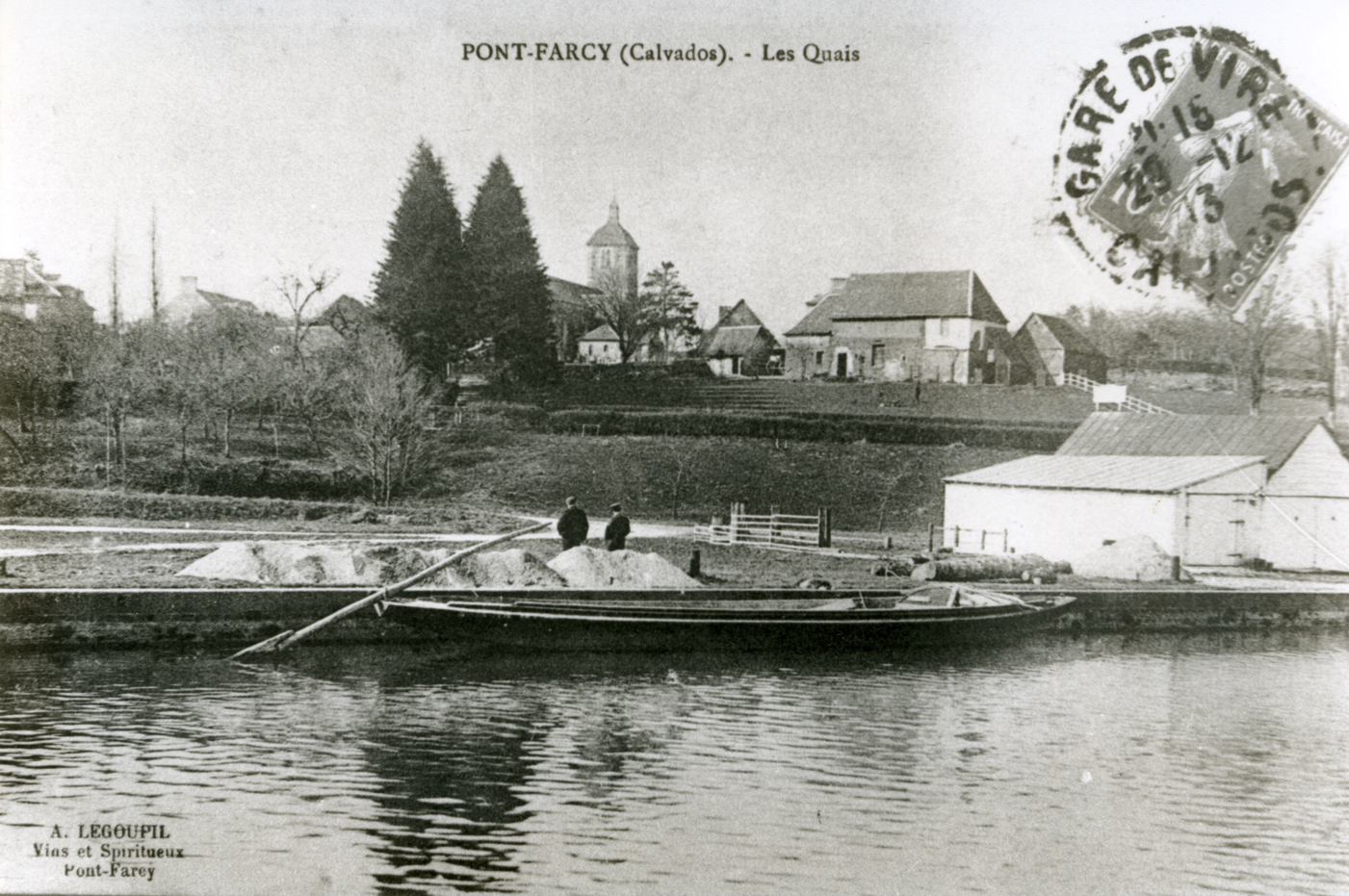

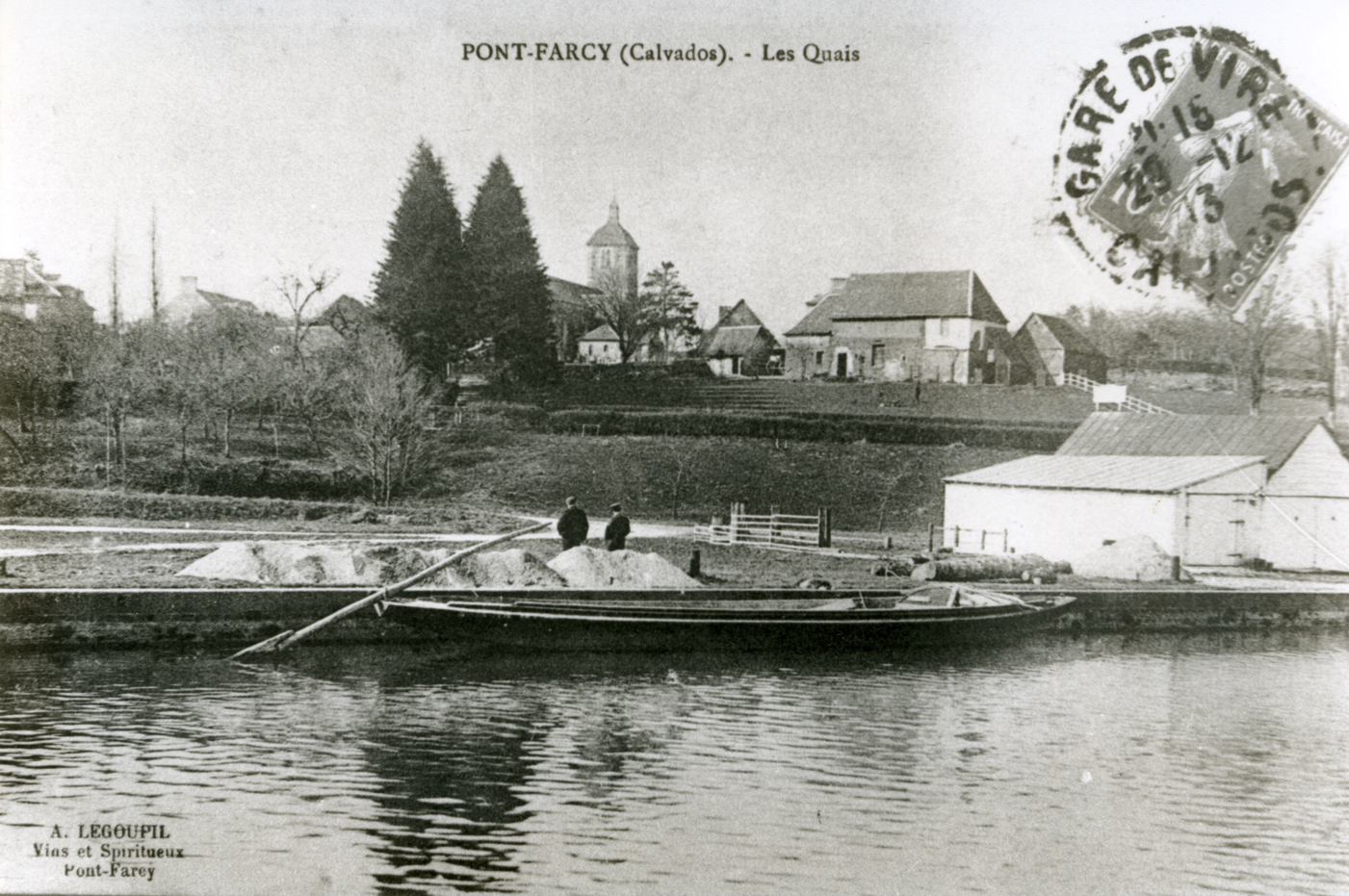

The canal, the port and the railways

I

n mediaeval times the river Vire was navigable as far as Saint-Lô and it's likely that small flat-bottomed barges could reach as far as Pont-Farcy when there was enough depth of water.

However, it wasn't until 1861 that a purpose-built canal was open all the way from the sea to Pont-Farcy.

However, it wasn't until 1861 that a purpose-built canal was open all the way from the sea to Pont-Farcy.

The Vire et Taute section of the canal near Carentan had already opened by 1839 but two years later a scheme to run a canal from the coast to Vire was abandoned.

This was hardly surprising since the course of the river and the gorges would have presented enormous technical and geological challenges.

This was hardly surprising since the course of the river and the gorges would have presented enormous technical and geological challenges.

Instead, in 1845, a plan to link Pont-Farcy with the coast was approved. Nineteen locks were needed and the state poured 2.6 million francs into the project. In 1861 the canal was opened and the barges, towed by horses on the tow-path, began a successful two-way trade on the canalised river.

Vast quantities of sea-sand fertiliser were brought upstream but the most important commodity was agricultural lime, quarried in the limestone hills north of St Lô and processed in lime kilns close to the canal around St Fromand and La Meauffe.

Vast quantities of sea-sand fertiliser were brought upstream but the most important commodity was agricultural lime, quarried in the limestone hills north of St Lô and processed in lime kilns close to the canal around St Fromand and La Meauffe.

This lime was to transform the lives and landscape of the bocage virois since it allowed farmers to develop the intensive dairy farming industry we known today and which, in the C19th, produced world-renowned dairy products such as Normandy butter and Camembert cheese. The barges did not return empty, however. So-called 'Vire' granite was transported overland to Pont-Farcy and shipped down-stream, along with vast quantities of local schist from Pont-Farcy's own quarries such as the Robbe quarry at La Grippe, to be used for building in rapidly expanding towns such as St Lô which were beginning to benefit from industrialisation.

This lime was to transform the lives and landscape of the bocage virois since it allowed farmers to develop the intensive dairy farming industry we known today and which, in the C19th, produced world-renowned dairy products such as Normandy butter and Camembert cheese. The barges did not return empty, however. So-called 'Vire' granite was transported overland to Pont-Farcy and shipped down-stream, along with vast quantities of local schist from Pont-Farcy's own quarries such as the Robbe quarry at La Grippe, to be used for building in rapidly expanding towns such as St Lô which were beginning to benefit from industrialisation.

So, for a short while Pont-Farcy became a busy inland port with merchants supplying lime and sea-sand fertiliser to local farmers who came to collect it in their farm carts while the quarries, such as Robbe's at La Grippe near Pont-Farcy, operated close to the canal so that they could load stone directly into the barges.

So, for a short while Pont-Farcy became a busy inland port with merchants supplying lime and sea-sand fertiliser to local farmers who came to collect it in their farm carts while the quarries, such as Robbe's at La Grippe near Pont-Farcy, operated close to the canal so that they could load stone directly into the barges.

But this golden era was brief. Almost as soon as the canals were constructed, the railways arrived to compete with them. At first it was cheaper to send low-value and bulky commodities by horse-drawn barge and the more expensive railways were best value only when speed was important and higher value commodities such as perishable foodstuffs like meat or dairy products were involved. But before long the cost of rail transport for passengers and goods dropped and small canals slowly died. There was still a little traffic on the canal after the First World War, but activity in the port of Pont-Farcy was in steep decline.

But this golden era was brief. Almost as soon as the canals were constructed, the railways arrived to compete with them. At first it was cheaper to send low-value and bulky commodities by horse-drawn barge and the more expensive railways were best value only when speed was important and higher value commodities such as perishable foodstuffs like meat or dairy products were involved. But before long the cost of rail transport for passengers and goods dropped and small canals slowly died. There was still a little traffic on the canal after the First World War, but activity in the port of Pont-Farcy was in steep decline.

• See La Vire Canalisée.

Les Commerces de Pont-Farcy en 1954 selon André Lelouvier

In the 1950s and 1960s, Pont-Farcy had at least 50 shops and businesses. These served the needs of the locality and thousands of people travelling through on the main road from Paris to Brittany.

In the 1950s and 1960s, Pont-Farcy had at least 50 shops and businesses. These served the needs of the locality and thousands of people travelling through on the main road from Paris to Brittany.

In those years millions of cars and lorries thundered through the narrow high street, both sides of which were lined with small shops and at least ten bars.

- 10 bars

- 5 Épiceries

- 4 Abattoirs

- 3 Bouchers

- 2 Forgerons

- 2 Moulins

- 2 Coiffeurs

- 2 Buralistes

- 2 Boulangeries

- 2 Cordonniers

- 2 Menuisiers

- 1 Charcuterie

- 1 Vendeur de vélos

- 1 Bouredellier

- 1 Mercerie

- 1 Marchand de tissus

- 1 Granitier

- 1 Cancaillier

- 1 Routier

- 1 Restaurant/hôtel

- 1 Electro-ménager

- 1 Vetérinaire

- 1 Marchand de meubles

- 1 Garde champêtre

- 1 Garage

- des Écuries

- les Pompiers

- la Gendarmerie

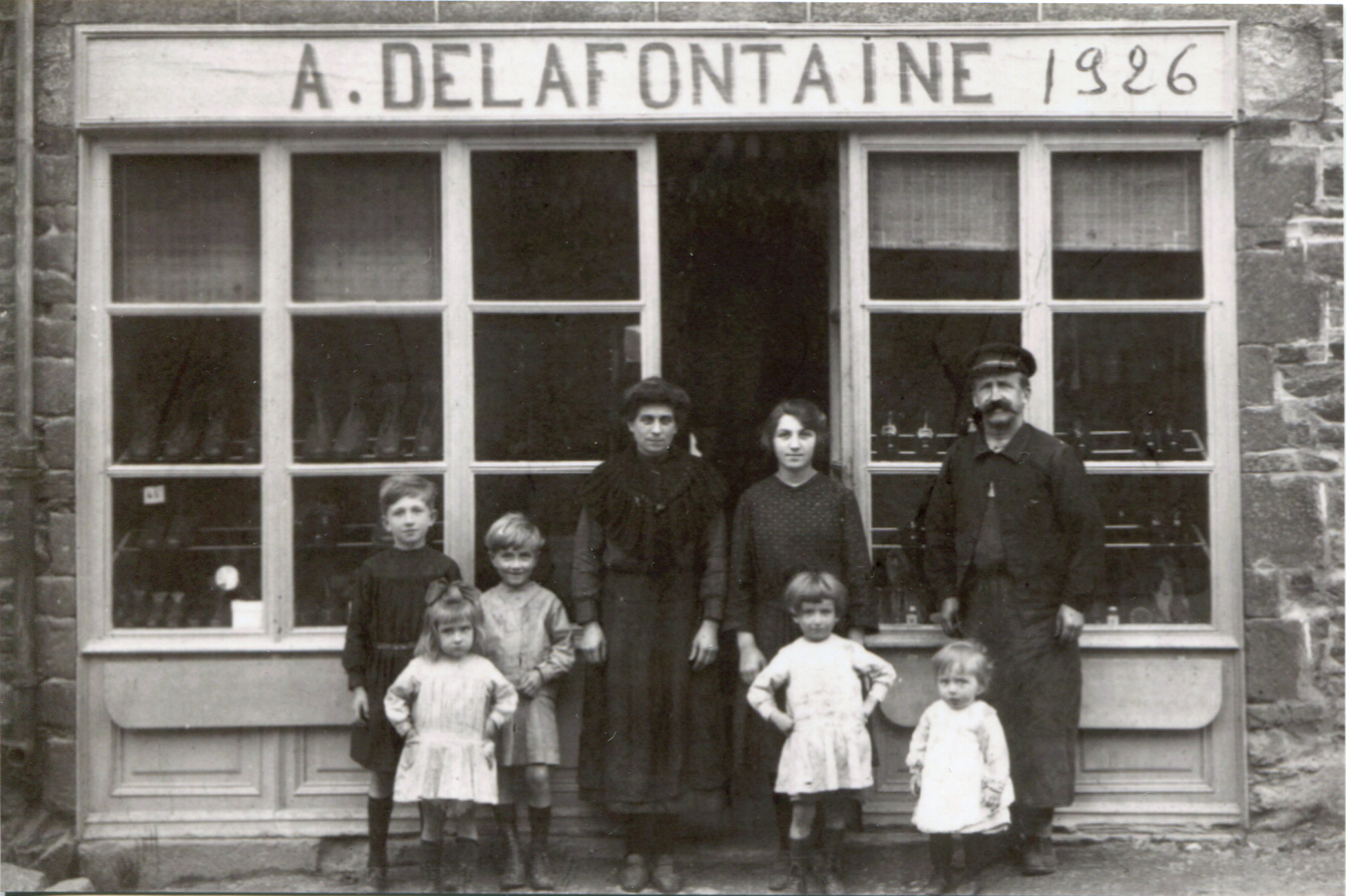

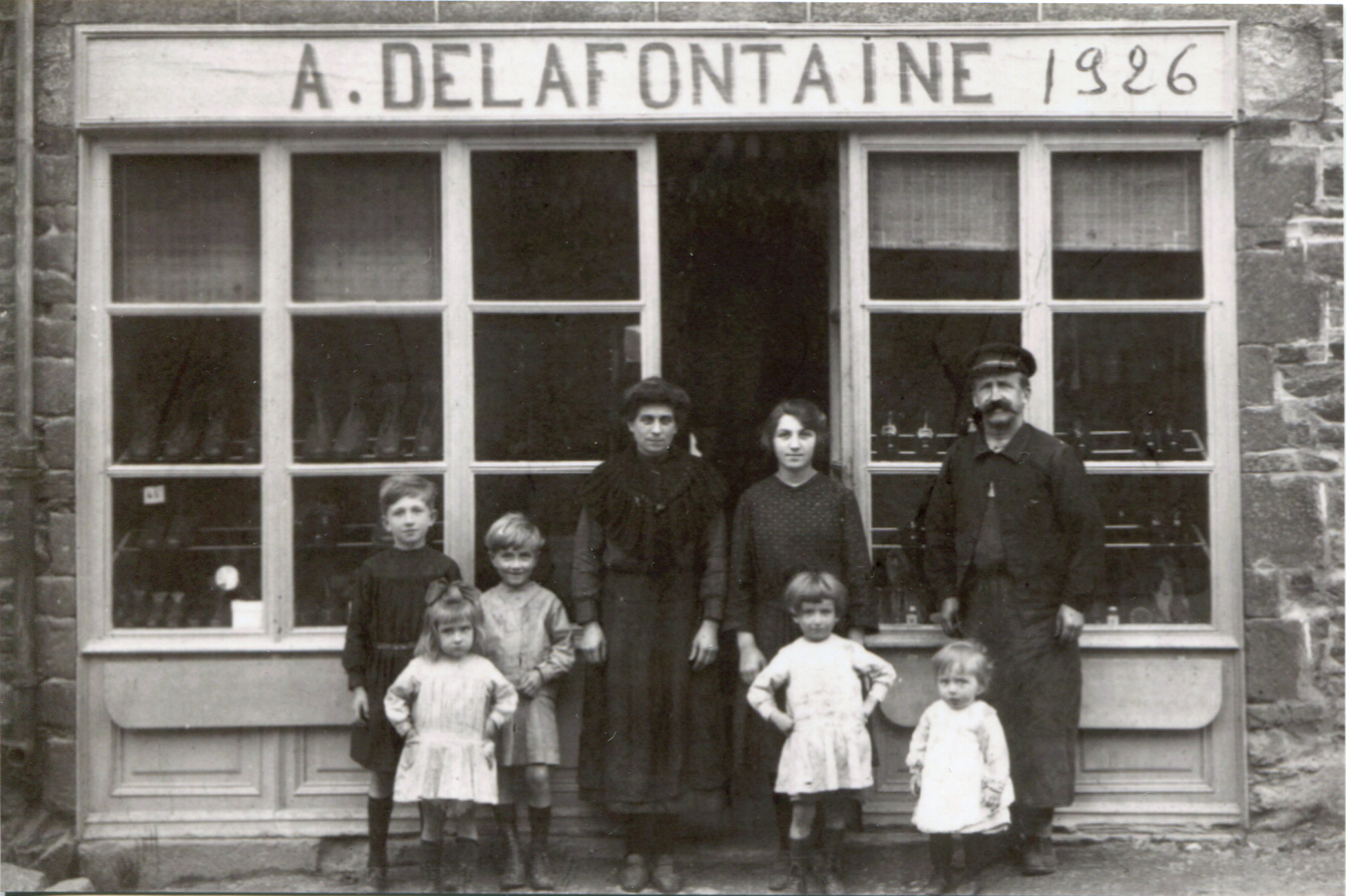

Click on the small pictures right and above to see rare surviving examples of the broad window-sill in French, un étale, which in English became a stall from which shopkeepers once sold goods 'over the counter' on which the money was counted out to clients standing in the street. The room behind was part of the shop-keeper's house.

Click on the small pictures right and above to see rare surviving examples of the broad window-sill in French, un étale, which in English became a stall from which shopkeepers once sold goods 'over the counter' on which the money was counted out to clients standing in the street. The room behind was part of the shop-keeper's house.

In the list above: the marchand de tissus also sold clothes; the abattoirs were abolished in 1961.

Les Disparus de trois guerres

Le mémorial aux disparus de la première guerre. Derived from the original plaque which in 2004 was mounted on the wall of the small meeting room above the ground-floor Mairie in Pont Farcy.

Le mémorial aux disparus de la première guerre. Derived from the original plaque which in 2004 was mounted on the wall of the small meeting room above the ground-floor Mairie in Pont Farcy.Léon Asselin 1914

Alphonse Godard 1914

Alphonse Hermon 1914

Marcel Jeanne 1914

Louis Laville 1914

Louis Manson 1914

Louis Pellerin 1914

Octave Postel 1914

Louis Salles 1914

Auguste Savary 1914

Auguste Voisin 1914

Albert Champin 1915

Alfred Gesnouin 1915

Alfred Lefèvre 1915

Paul Lefèvre 1915

Paul Leparquet 1915

Raymond Potier 1915

Jules Salles 1915

Abel Voisin 1915

Réné Yver 1915

Gaston Angot 1916

Auguste Barbier 1916

Auguste Belluet 1916

Paul Deguette 1916

Henri Laurent 1916

Louis Masset 1916

Louis Voisin 1916

Joseph Tirel 1916

Henri Champin 1917

Constant Gripon 1917

Eugène Haye 1917

Auguste Ladroue 1917

Henri Laville 1917

Henri Loisiel 1917

Désiré Marie 1917

Louis Cannet 1918

Prosper Delahaye 1918

Réné Gesnouin 1918

Alphonse Lefèvre 1918

100 years later the following names were still to be found in Pont Farcy: Godard, Hermon, Jeanne, Laville, Manson, Savary, Voisin, Gesnouin, Barbier, Deguette, Ladroue, Loisiel et Marie.

Alphonse Lefevre 1940

Albert Lefevre 1940

Ate Hermantier 1941

Emile Sorée 1945

Civiles 1944

Marie Boscher

Edith Enée

Asine Lefevre

Americans killed

Americans killed2 Aug 1944

liberating Pont-Farcy

Orin L. Daulton

Guido N. Delia

Philip G. Gresser

Joseph M. Lamuth

Alfred A. Simon

Carl E. Webb

James Hoy

Robert L. Keele

Guerre Indochine

Raymond Sanson 1946

Memorials...

• La Grande Calvaire: near the south door of the church

• La Grande Calvaire: near the south door of the church• Le Monument aux Morts: at the entrance to the churchyard

• La Grande Calvaire: above Le Vivier opposite the school

• Le Pont Bailey: Mémorial de la Bataille de Normandy: in the old 'port'

• Mémorial Américains aux neuf tombés le 2 August 1944: on the Route de Tessy

• Calvary Cross Beau Chêne: on the border with Gouvets

• La Vierge de Lourdes: in the high street

• Le Calvaire du Cimetière de Pont-Farcy: on the Vire road and actually on land in Ste Marie-Outre-L'Eau

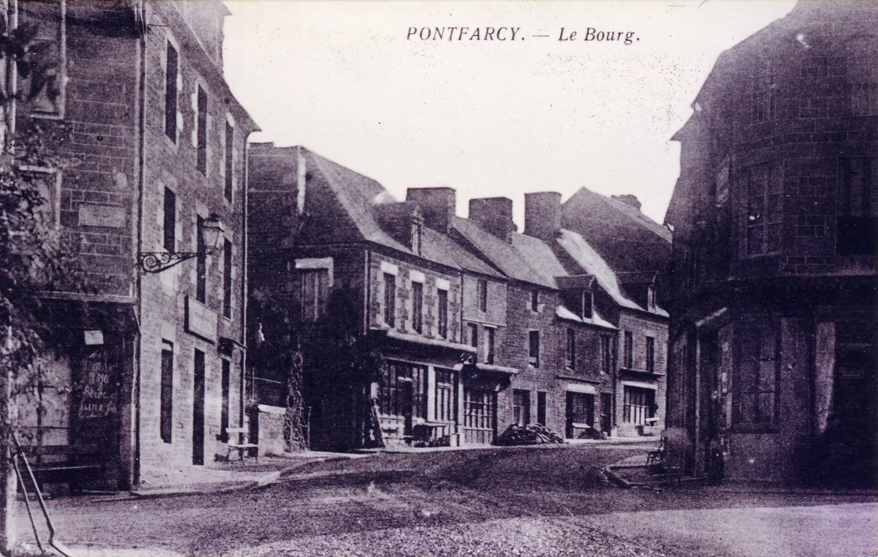

The high street

W

hen we look at the bourg today it we see an almost unbroken row of stone built houses down both sides of the street. But in fact the character and history of the two sides are almost certainly very different.

Even a brief glance of the cadastre map shows that most of the houses on the south side are built on almost uniform narrow plots of land stretching from today's high street down to what is called the Bas du Bourg with its mill-race and stream. Here most houses had their own well and latrine which emptied into the stream and all the houses had access either to their own or to a communal lavoir.

The land-distribution on the south side seems to accord with a form of 'town plan', each house having plenty of light, a useful garden in a well-defined rectangular plot, and access to water.

But a more careful study of the cadastre map reveals that at one time all the land along the north side of the street was probably divided among only about about seven plots:

But a more careful study of the cadastre map reveals that at one time all the land along the north side of the street was probably divided among only about about seven plots:

- The area of land now occupied by Pont-Farcy's school and stretching back at least as far as today's sports field. A surviving building on this site may have C16th or C17th. It is possible that that this plot "A" once formed part of a larger holding that incorporated both "A" + "B". The fact that this plot became 'commune' land probably following the French Revolution may be significant.

- The area of land now occupied by the Mairie and stretching back at least as far as today's sports field. It is possible that that this plot "A" once formed part of a larger holding that incorporated both "A" + "B". The fact that this plot became 'commune' land probably following the French Revolution may be significant.

- The area of land which almost certainly once belonged to Le Croissant and stretching back at least as far as today's sports field. See the area marked red in the image above. A narrow track, of probably ancient origin, runs up its eastern side separating it from what appears to be a similar adjacent property see 'D'.

- An area of land which may once have been occupied by a substantial house perhaps like Le Croissant? which stretched back at least as far as today's sports field and was bounded on its eastern flank by the Route de Montabot.

- The area of land which may once have formed part of the church's land or which may have been privately owned. It is bounded on its western flank by the Route de Montabot. It is traversed by a small lane leading from the Route de Montabot to the church and if this lane is of ancient origin the designation and boundaries of the land might be easier to understand. Interestingly there is a very narrow passage separating the houses facing east from those facing west. [NB This plot "E" might have formed part of a larger holding incorporating "E" + "F".]

- The area of land belonging to the Church of St Jean. Before the French Revolution, the church presumably owned the land currently occupied by the church, its churchyard and the Presbytery behind, as well as the entire area occupied by the Bureau des Postes, the council depot, the Salle des Fêtes, etc. It is significant that no shops or commercial premises appear to have existed along this stretch of the high street until after 1789 at least. The church's land holdings may also have included the parcel described at "E" above and also further land around or beyond the Presbytery as far as the quarry more research needed.

- The area of land, largely intact, which remains in private hands and is occupied by one of the grander houses of Pont-Farcy. The Route des Carrières along its eastern flank is surely of ancient origin and once led not only to the quarries but to the Moulin-sous-le-Bosq. The northern boundary may once have extended as far as the quarry since the lane linking the Route de Tessy with the church is of recent origin.

- The farm...

Although small houses now line the north side of the road, it's clear that they are huddled together in a narrow strip along the road and there's little evidence of 'planning'. In all probability these houses were built on...

THIS ITEM IS UNFINISHED!

Le Croissant

N

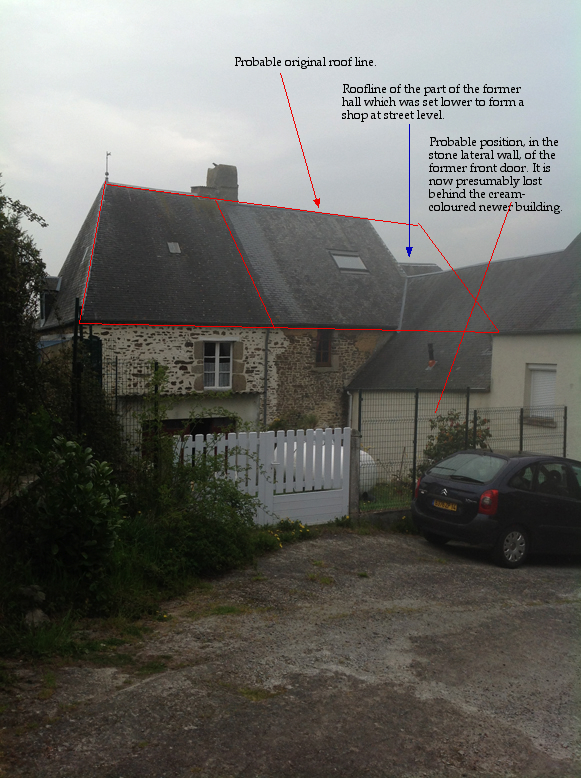

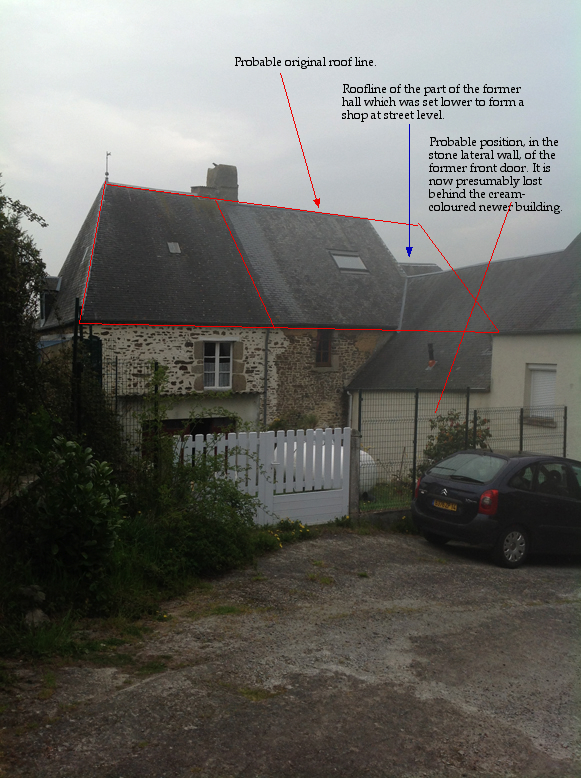

o detailed analysis of Pont-Farcy's older houses has yet been carried out but probably the oldest so far identified in the bourg is Le Croissant.

Many surviving elements of this house are typical of local manor houses of the C16th of which this is an impressive example.

About half of the original hall survives, dominated by a massive fireplace in the north gable with a huge, standard-issue granite mantel supported on four corbels – the mantle having been moved backwards long ago. Decoration of the granite pillars includes scallop shells, crosses and so-called pilgrim's sticks. Overhead a truly massive oak beam remains in situ though it seems likely that there was once a second such beam which did not survive the modifications necessary to turn part of the hall into a shop see below.

The historian David Nicolas-Méry suggests that the name Le Croissant might well refer to the symbol on a sign that once hung at that site. He adds, however, that the croissant was the emblem chosen by Henri ll of France to symbolise catholicism and it could be that the owners of this house in the late C16th were making a bold statement of their beliefs by associating their house with catholicism in a largely protestant area around the time of the Wars of Religion.

The historian David Nicolas-Méry suggests that the name Le Croissant might well refer to the symbol on a sign that once hung at that site. He adds, however, that the croissant was the emblem chosen by Henri ll of France to symbolise catholicism and it could be that the owners of this house in the late C16th were making a bold statement of their beliefs by associating their house with catholicism in a largely protestant area around the time of the Wars of Religion.

An almost intact stairway tower survives in the east wall, rising two storeys high but with evidence that the stairway once rose to the level of a third floor.

The original front door, now gone, was almost certainly in the western lateral wall, probably giving onto a courtyard whose shape is still still discernible from the cadastre plan.

In the corresponding western wall, beside the stairway tower, is a superb mullioned window with renaissance decoration and original iron grill, surrounded by other embrasures, one of which is still fitted with its original grill.

Indoors, round-arched interior doorways suggest that the original house extended to the north, probably with a service room or store-room at ground level and a seigneurial room or rooms on the first floor. The original front door may have had a similar round arch. The paving flags shown in a sketch of the room by Arcisse de Caumont in 1857 are no longer visible but may perhaps survive beneath the modern floor.

Indoors, round-arched interior doorways suggest that the original house extended to the north, probably with a service room or store-room at ground level and a seigneurial room or rooms on the first floor. The original front door may have had a similar round arch. The paving flags shown in a sketch of the room by Arcisse de Caumont in 1857 are no longer visible but may perhaps survive beneath the modern floor.

In addition to the mullion window, an external stairway tower survives at Le Croissant. Like several other similar towers e.g. L'Aumoire at Morigny and La Ricouvière at St Vigor-des-Monts the tower would have risen three storeys high although the house is thought to have had only two habitable floors. We still do not know why this was so although in some cases there is evidence that the tower incorporated a sort of 'chimney' that allowed soil from a latrine at the top to fall to a collection point within the foot of the tower.

Sadly, the external form of the southern half of the hall is now obscured by two newer buildings which abut the southern ends of the east and west lateral walls, both newer buildings facing the high street.

The new building on the western side may have led to the loss of the manor house's original front door and probably its main west windows – both of which were probably impressive judging by the quality of the surviving mullion window in the back wall. But despite the new structures the original shape and volume of the hall survives even though it's floor level and roof height have been dramatically altered in the southern half.

This southern end of the original hall is now at street level, about a metre lower than the intact remains of the old hall. The lower area was almost certainly created to serve as a shop in the C18th or early C19th and, although the house has now been converted back to domestic use, the impressive shop-front 'counters' looking like extra-wide window-sills are still visible today. It may be that a second massive beam was removed from the hall in order to make this conversion.

This southern end of the original hall is now at street level, about a metre lower than the intact remains of the old hall. The lower area was almost certainly created to serve as a shop in the C18th or early C19th and, although the house has now been converted back to domestic use, the impressive shop-front 'counters' looking like extra-wide window-sills are still visible today. It may be that a second massive beam was removed from the hall in order to make this conversion.

This change of use and of floor level demonstrates the growing importance of Pont-Farcy as a commercial centre and is particularly significant since it parallels the rise and fall of the town's commercial history as a whole. At some stage a once-grand manor house was transformed into commercial premises but became a house again when town's commercial life died in the 1970s. The front door – which once faced west over its own land – was turned to face a busy and noisy commercial high street, though today it is scarcely used at all!

This change of use and of floor level demonstrates the growing importance of Pont-Farcy as a commercial centre and is particularly significant since it parallels the rise and fall of the town's commercial history as a whole. At some stage a once-grand manor house was transformed into commercial premises but became a house again when town's commercial life died in the 1970s. The front door – which once faced west over its own land – was turned to face a busy and noisy commercial high street, though today it is scarcely used at all!

The high street we know today was probably created from a narrower existing lane. It obviously involved substantial deepening in order to produce a suitable gradient for carts and would have required widening in order to produce enough space for shop fronts, pedestrians and market stalls. In any case, the effect of creating the new road can be seen in several old houses on the north side of the road: either you have to climb steps to reach their front doors or, as at Le Croissant, a whole front room had to be lowered to street level.

A Mystery at La Hatuyère...

A

t about the highest point in Pont-Farcy – a spot overlooking the entire valley of the Vire from Tessy to Ste Marie-Outre-L'Eau, with views almost as far as St Lô and Vire – there exists a mystery feature. Now you see it... now you don't...

On the 1832 Napoleonic cadastre there is a curious, oval-shaped road at this dominant position known as La Hatuyère. Today there is no sign of what this feature might once have been, but by super-imposing the 1832 hand-drawn map onto a Google Earth satellite image one can clearly see the existance of an oval-shaped road or path.

It is remarkable enough that the early C19th hand-drawn map so closely resembles today's aerial view using C21st technology, but the fascinating question remains that nowhere else nearby does such a precisely oval-shaped feature appear. It must have served a man-made purpose in itself and its form must surely be the consequence of a man-made structure that no longer exists but which once stood either within or around the oval road.

It is remarkable enough that the early C19th hand-drawn map so closely resembles today's aerial view using C21st technology, but the fascinating question remains that nowhere else nearby does such a precisely oval-shaped feature appear. It must have served a man-made purpose in itself and its form must surely be the consequence of a man-made structure that no longer exists but which once stood either within or around the oval road.

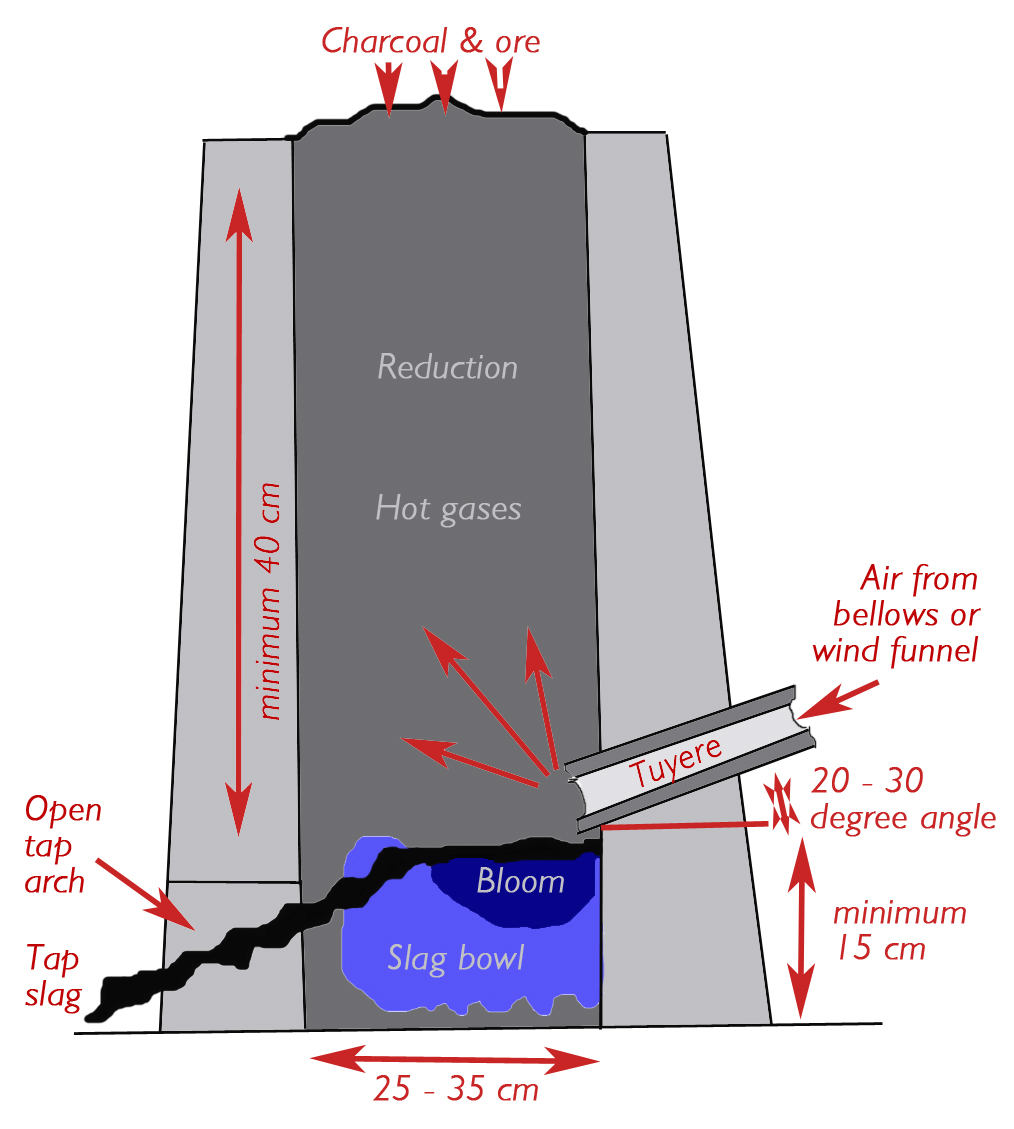

In 2014 Christopher Long suggested that La Hatuyère is probably a corruption of La Haute Tuyère. A tuyere (in both French and English) is the funnel-shaped structure that directs wind into a furnace. In the late Middle Ages the air delivered to a bloomery furnace through a tuyere was often pumped under pressure by bellows.

We are most grateful to industrial archaeologist Robert Waterhouse who has described a system – often found on exposed hill-tops – which involves two narrowing wattle-and-daub walls which capture and funnel natural wind into the furnace. La Hatuyère is notable for being at a dominant high point, exposed to winds from all directions.

We are most grateful to industrial archaeologist Robert Waterhouse who has described a system – often found on exposed hill-tops – which involves two narrowing wattle-and-daub walls which capture and funnel natural wind into the furnace. La Hatuyère is notable for being at a dominant high point, exposed to winds from all directions.

The question remains: what purpose would a 'bloomery' or 'blast' furnace have served at La Hatuyère?

The question remains: what purpose would a 'bloomery' or 'blast' furnace have served at La Hatuyère?

The Mariette de la Pagerie map for this area (based on surveys 1690-1720) marks La Hatuyère (Pont-Farcy) as a source of tin [alchemical symbol 24]. Christopher Long, meanwhile, has presented a prima facie case for an artisan iron industry in a small valley about 500-900 metres away, across the river Vire, in Pleines-Oeuvres.

Local footpaths and ancient roads

This subject will be treated in a separate and detailed study which will be published in due course!

Pour savoir ce qu'il en est des chemins communaux inscrits dans le PDIPR.

Pour savoir ce qu'il en est des chemins communaux inscrits dans le PDIPR.

See images of Pont-Farcy's paved Roman road which is currently used as a refuse tip and is closed to public access (illegally?) by a padlocked gate.

On the face of it, there is nothing that would preclude the possibility that this is a Roman road. It could be later, but looking at the Cassini map, the topography suggests that the road's location has been the logical place for a human trackway for as long as human communities have inhabited this area. The connection with Pont Farcy, which could have originated as a vicus/statio/mansio at the junction of a Roman road and river crossing, only adds to the possibility that we may be looking at a Roman road. And even if the paving that is now visible is more recent, that too would do nothing to eliminate the possibility that it was preceded by a Roman roadway. Perhaps the only way to resolve the question would be to do some archival work on Pont Farcy in the Middle Ages and early Modern period to see if the road is any way associated with the king, dukes of Normandy, or other local authorities. Bruce Hitchner: historian and archaeologist, Professor of Classics & International Relations at Tuft University.

Clockmakers

Pont-Farcy was renowned in the C18-19th for its clock-making. But although a number of clocks are specifically stated to have been made there, it is likely that Pont-Farcy was particularly known for the manufacture of clock components – in high-grade, well-crafted iron – which were bought and assembled by clockmakers throughout the region. This would help to explain why almost any 'lantern' clock of this era was commonly and generically known as an horloge de Pont-Farcy.

Pont-Farcy was renowned in the C18-19th for its clock-making. But although a number of clocks are specifically stated to have been made there, it is likely that Pont-Farcy was particularly known for the manufacture of clock components – in high-grade, well-crafted iron – which were bought and assembled by clockmakers throughout the region. This would help to explain why almost any 'lantern' clock of this era was commonly and generically known as an horloge de Pont-Farcy.

In ca. 2005, Raymond Manson of St Vigor-les-Monts noted that among the makers known were 'Alexandre à Pontfarcy 1750' and a 'Bunel F.A. Pont-farcy' who, on another clock dated 1750, signed himself 'Bunel A Pont-farcy'. Meanwhile an early C19th clock is signed 'Lemarchand Alexandre Pont-farcy'.

... On retrouve souvent dans l'histoire de la fabrication des premières horloges les mêmes conditions: dans un lieu ou il y a du fer facile à récupérer (zones d'affleurement de minerai) du bois qui est transformé en charbon de bois et une rivière pour fournir la force hydraulique. Les paysans lors de leurs moments perdus les utilisent pour fabriquer des instruments aratoires élémentaires comme les socs de charrue, des outils simples comme les serpettes, des clous pour ferrer les chevaux, puis des armes de chasse, certains en font un métier et fabriquent des serrures, d'autres font des armes à feu et un beau jour on leur demande de faire une horloge. Mais ce n'est pas une industrie on fait une horloge à la demande. Ce n'est que un peu plus tard à Morez et ses alentours et dans le sud de la Foret Noire que petit à petit ces travaux passent du stade artisanal au stade semi-industriel... Richard CHAVIGNY

However, the best study of Pont-Farcy clocks is : L'Horlogerie Vernaculaire Bas-Normande by David Nicolas-Méry (2012). He too believes that Pont-Farcy was a likely source for the components used by many clock-makers in Basse-Normandie.

Résistance

Lieux des évènements du résau 'PTT' Résistance pendant la seconde guerre mondiale – munitions britanniques parachutées par le RAF sur les hauts de Ste-Marie-Outre-L'Eau.

Age of motoring

Nevertheless, during the 1920s and 1930s, Pont-Farcy continued to prosper thanks to the growing popularity of motor cars. Motorists needed its hotels, garages, bars and restaurants as they took the main road from Paris via Caen to Mont-Saint-Michel and Brittany.

Nevertheless, during the 1920s and 1930s, Pont-Farcy continued to prosper thanks to the growing popularity of motor cars. Motorists needed its hotels, garages, bars and restaurants as they took the main road from Paris via Caen to Mont-Saint-Michel and Brittany.

World War ll

During World War ll, the bridge at Pont-Farcy was once again strategically vital. By 1940 the Germans occupied all of France and the bridge at Pont-Farcy guaranteed their communications across central Normandy and into Brittany. In 1944 the largest amphibian invasion ever known took place when British, Canadian and American troops landed on beaches in Normandy in order to liberate France and the rest of Europe.

During World War ll, the bridge at Pont-Farcy was once again strategically vital. By 1940 the Germans occupied all of France and the bridge at Pont-Farcy guaranteed their communications across central Normandy and into Brittany. In 1944 the largest amphibian invasion ever known took place when British, Canadian and American troops landed on beaches in Normandy in order to liberate France and the rest of Europe.

Broadly speaking, the river Vire separated the American forces in the west – liberating the Cotentin peninsula, Avranches, Mortain and Brittany – from British and Canadian forces in the east – liberating the region from Caen to Bény Bocage, including Vire itself.

Broadly speaking, the river Vire separated the American forces in the west – liberating the Cotentin peninsula, Avranches, Mortain and Brittany – from British and Canadian forces in the east – liberating the region from Caen to Bény Bocage, including Vire itself.

To prevent the Germans from retreating eastwards across the river Vire, American aircraft spent days trying to bomb the bridge at Pont-Farcy. They failed, though many of the town's houses were destroyed.

Eventually the Germans retreated across Pont-Farcy's bridge and destroyed it themselves with dynamite to cover their retreat.

A few weeks later they were annihilated in a pincer movement involving British and American troops at Falaise.

The author would like to thank a number of people whose help has been invaluable in preparing this page.

Special thanks are due to the archivist and historian Jacky Brionne of the Archives Départementales de la Manche at St Lô, who combed the sparse surviving church records for Pont-Farcy which he published in 2006 and dedicated to the memory of L'Abbé Paul Vallée. See: Records of the Parish of Pont-Farcy.

The historian Dominique Doublet, himself a descendant of the Farcy family, has been most generous in sharing his remarkable discoveries in France and England, some of which directly concerns Pont-Farcy's mediaeval past. A copy of his work is deposited with the Archives Départementales de la Manche at St Lô.

For many years Henri Letellier has been generous friend and guide. Formerly a farmer, Henri has devoted much of his retirement to recording Pont-Farcy's history and the memories of many of its inhabitants. His work, in words and photographs, ranges from mills, bread-ovens and wells to the memories of local contemporaries who served in Algeria. He has exhibited much of his work and published some of it. Pont-Farcy is not renowned for the importance it places on its heritage, but Henri Letellier's work will one day provide a fascinating and invaluable resource. Many thanks also to André Lelouvier for his memories of the town in the 1960s.

The author would like to thank the Mayor and conseil municipale of Pont-Farcy for permission to reproduce scans of the 1832 cadastre, digital copies of which have been offered to the commune for archival safe-keeping. Thanks are also extended to the following for generously providing some of the photographs illustrating this page. They include: Henri Letellier, Jean Delafontaine and Georges de Coupigny. A great debt too is owed to industrial archaeologist Robert Waterhouse whose analysis of water management in the Tison valley and of the possible uses of La Hatuyère site were of immense value.

Pont-Farcy ca 1900-50 Further images, ca 1900-1950, illustrating subjects on this page

Pont-Farcy Cadastre Plan:– Summary of the entire commune with new road addition removed.

Pont-Farcy Cadastre Plan:– Summary of the entire commune with new road addition.

Pont-Farcy Cadastre Section A Sheet 2:– Le Val de Vire, La Championnière, Sur le Bosq, Le Moulin de Sous-le-Bois, Bourg de Pont-Farcy.

Pont-Farcy Cadastre Section B Sheet 1:– Les Noes, La Clémendière, Le Moulin Hy, Le Haut du Bourg, Bourg de Pont-Farcy.

Pont-Farcy Cadastre Section B Sheet 2:– Les Monts, La Benouvière, Beauregard, La Sallière, La Sourcière, Le Moulin Hy, Le Bôquet.

Patois & The Norman Bocage Today First steps in understanding patois and Norman habits 2002

Normandy: The Search For Sidney Bates, VC A story of outstanding courage in the Battle of Normandy 2003

Les Frères Duval et Leurs Aviateurs Americains American airmen hidden in Pont-Farcy in WWll 2003

Tales of The Magic Wardrobe Explaining history through strip cartoons 2007

Mont Saint Michel in Normandy and St Michael's Mount in Cornwall Linking two St Michael's Mounts 2007

Tonsures, Tin, Bronze and Bells A study of Norman links to the Cornish tin trade 2009

St Michel, l'Étain et l'Âge des Cloches Talk given at the Archives Départementales, St Lô 2009

Baraquements Emergency Housing for the Battle of Normandy's homeless 2013

L'Horlogerie Vernaculaire Bas-Normande par David Nicolas-Méry with references to Pont-Farcy 2012

An Iron Industry in the Bocage Virois? a study of an apparent iron industry in and around Pont-Farcy by Christopher Long 2014

Note the work of historian Dominique Doublet whose studies are particularly associated with: Farsi/Farcy/Pont-Farcy; Mesnil-Guérin and Mainwaring; Chapelle-Heuzebroc; Guilberville; Soligné/Soligny; Beuvrigny; Saint-Louet-sur-Vire; Pleines-Oeuvres; Vire; Isigny; Terregate/Beuvron; Coutances Chester; Somerset; Comté de Dol.

D. DOUBLET Farcy De Guilberville 1 Text

D. DOUBLET Farcy De Guilberville 1 Charts

D. DOUBLET Farcy De Guilberville 2 Text

D. DOUBLET Farcy De Guilberville 2 Charts

D. DOUBLET Images

D. DOUBLET The Initiation of Big Grey Wolf

© 2006 Christopher Long. Copyright, Syndication & All Rights Reserved Worldwide.

The photographers responsible for some images on this page appear to be unidentifiable.

The author would be happy to credit or acknowledge any photographer whose identity can be reliably established.

The text and graphical content of this and linked documents are the copyright of their author and or creator and site designer, Christopher Long, unless otherwise stated. No publication, reproduction or exploitation of this material may be made in any form prior to clear written agreement of terms with the author or his agents.

The amazing industrial Norman cow

T

he appearance of the Bocage Virois in Normandy is the consequence of an astonishing C19th agricultural revolution. Until then, the region was famous for its arable crops and its sheep. But in 1861 the Vire Canal linking the chalky Norman coast to towns inland, permitted the delivery of huge quantities of cheap lime and fertiliser to the new 'port' at Pont-Farcy – enough to allow an almost overnight conversion to dairy farming.

Above: Local farmer Mickael Barbier with a prize-winning normande. This ideal all-round breed was created in the mid-19th century by crossing a local Normandy cow with a beefy Durham bull from England and crossing the result with the milky Jersey breed from the Channel Islands.

The new railways guaranteed that meat, milk, cream, butter and cheese could all be delivered to Paris and other major towns in a few hours. Tens of thousands of designer-bred 'normande' cows filled the countryside and transformed it into the 'ancient' and 'traditional' landscape for which Basse-Normandie became famous: the little fields and apple orchards surrounded by trees and hedges. This was the terrain that made the Battle of Normandy so difficult for the Allies in WWll. This landscape is today being transformed again, this time into vast empty stretches of arable prairie. If the C19th landscape is fast vanishing, thousands of houses and farm buildings are still evocative of the C19th dairy revolution, provided you know what to look for...

• See Farm Structures in the Bocage Virois.

Pont-Farcy's church clock

I

n 2012 Pont-Farcy finally recognised the importance and value of its magnificent church clock. The mechanism had been a gift, in 1910, to Pont-Farcy by a certain Mlle Joséphine Louise Hurel who had died the year before. But sixty years later electricity had replaced clockwork and by 2007, though still in perfect working order, the gleaming mechanism had been abandoned and forgotten in the church. It took some determination to persuade the town to bring it down and put it on display in the church entrance.

• See: Pont-Farcy's Church Clock.

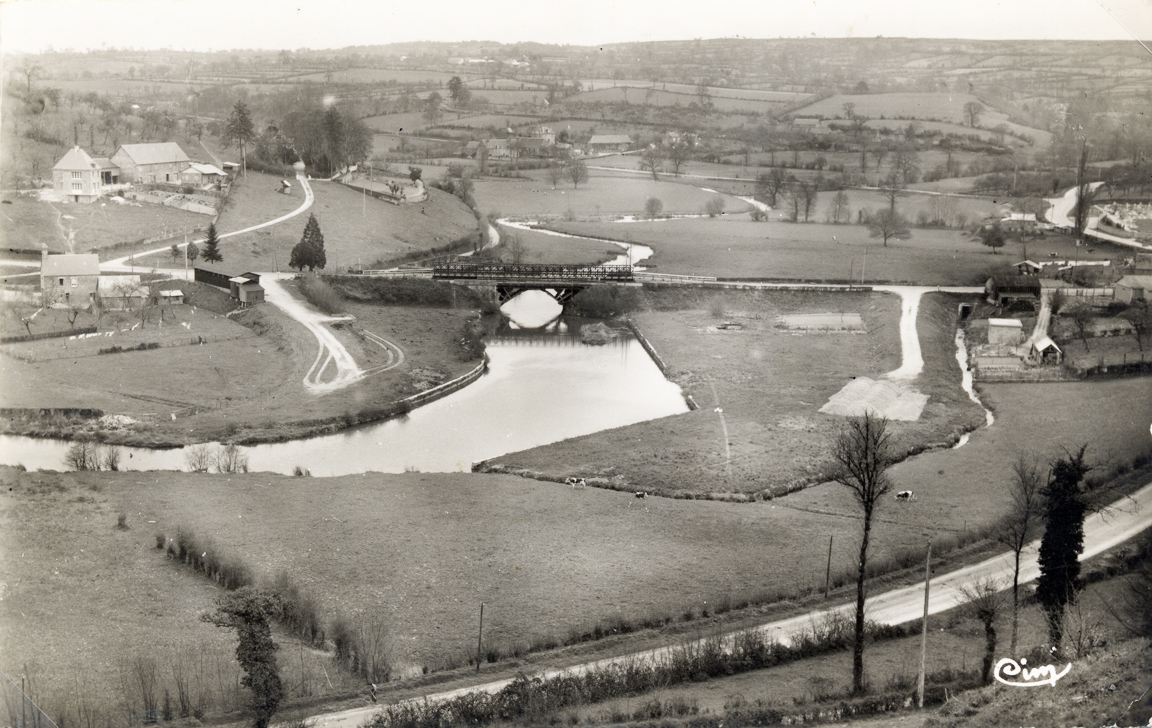

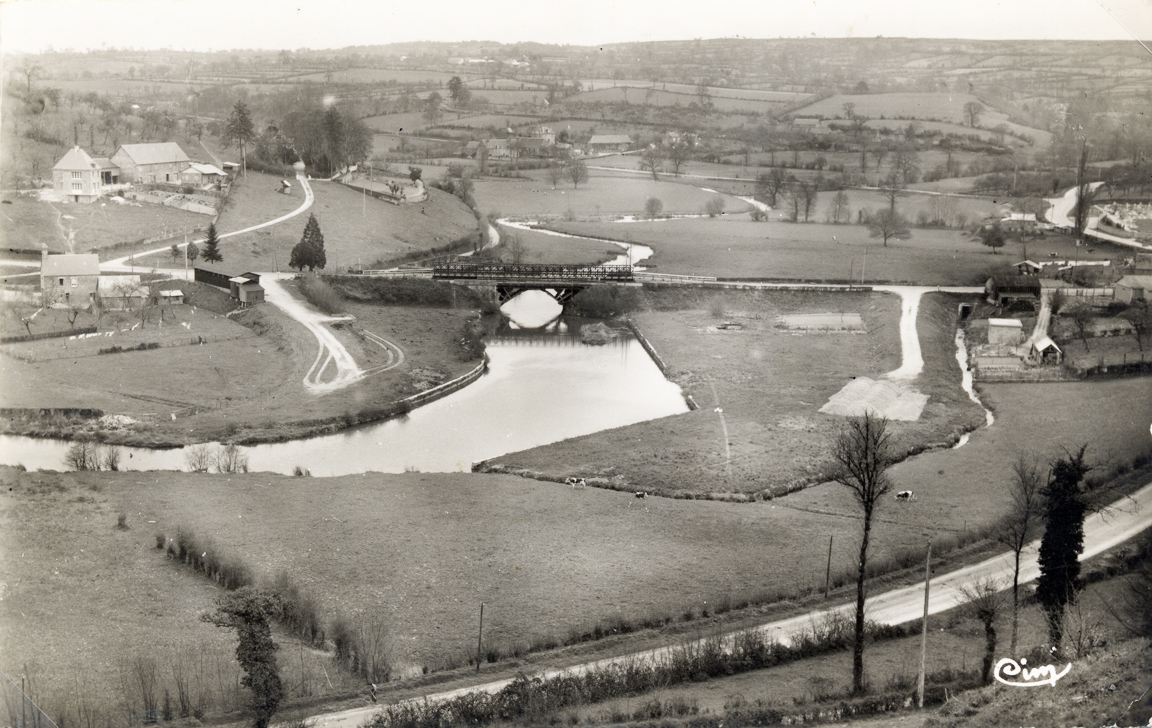

The last Bailey bridge in Calvados

J

ust a day or two before it was due to be cut up for scrap, in the summer of 2008, Les Amis du Pont Bailey were able to save the last WWll Bailey bridge in Calvados and preserve it as a memorial to all those who gave their lives or liberty for the freedom of Normandy. These military bridges had been designed by an Englishman, Sir Donald Bailey, and this particular one had served the British artificial Mulberry Harbour at Arromanches within a few days of the D-Day landings in 1944.

But from 1958-2008 it had been reused as a road bridge over the river Vire between Pont-Farcy and Fourneaux at La Grégardière. In 2008, with the help of British sappers of the Royal Corp of Engineers, the monster bridge 27 metres long and weighing 24 tonnes was first dismantled, then moved three kilometres up-river.

Finally six of the original nine sections of the bridge were re-built on the banks of the Vire in the former 'port' at Pont-Farcy. All this was done by voluntary effort, supported by hundreds of 'friends' in France and around the world, without recourse to a penny of public funding.

• See: Saving A Bailey Bridge

• See: Bailey Bridge Panel Text.

Hope and light in the darkness of war

F

or France, the German occupation in WWll remains a painful topic, but in the long dark days of 1940-44 there were moments of warmth and humanity despite the humiliation. As elsewhere in northern France, German soldiers were billeted with most families and farms in Pont-Farcy, while many of the menfolk of these families had already been shipped to Germany as forced labour.

Yves Langlois, later abbot of St Sever, was a young trainee priest during the war and was determined to avoid being taken as an 'STO' forced labourer. Instead he spent years working on farms and hiding with friends to avoid the German authorities. As an elderly man, and almost blind, he wrote out his memories of a one-man resistance campaign and also recorded a touching story of love and kindness in wartime Pont-Farcy which offered a small ray of light in sombre times.

• See: Souvenirs d'un Réfractaire au STOF and The Print Version

• See: Light in the Darkness at Pont-Farcy.

Saving a British whale

W

hen the Allies invaded Normandy in June 1944 they built two artificial harbours allowing men and materiel to be delivered to the battlefields as quickly as possible. These harbours had been designed and built by the British who towed the various elements across the Channel in the days immediately after D-Day 6th June and assembled them into giant floating ports at Arromanches Mulberry B, for the British and Vierville Mulberry A, for the Americans. Part of the harbour system consisted of several kilometres of floating roadway between the floating pier-heads and the shore. Each floating roadway consisted of a massive chain of 'Whales' each attached to the next by a floating 'Beetle'. The American harbour was soon destroyed by an unprecedented gale but the Arromanches harbour was used until other ports in northern France were liberated towards the end of 1944.

After the war many of the floating roadway Whales were temporarily re-used throughout Normandy and the rest of France where road bridges had been destroyed by the war. They weigh 27 tonnes and are over 24 metres long. One of these Whales found a home in Pont-Farcy where it was used to bridge the river Vire, linking La Grippe quarry with main Tessy road. In 1990 one of its concrete supports was washed away in a flood.

It might have melted down for scrap but fortunately it was preserved in pieces in another quarry near Brécey until 2012 when it was given to Les Amis du Pont Bailey to be preserved for posterity.

It might have melted down for scrap but fortunately it was preserved in pieces in another quarry near Brécey until 2012 when it was given to Les Amis du Pont Bailey to be preserved for posterity.

Right: The British engineer Alan Beckett invented the Whale and the associated elements of the floating roadways of the Mulberry artificial harbours. He is seen here (wearing a bow-tie) visiting the doomed Whale at Pont-Farcy in 1994, four years after floods washed away one of its supporting concrete pillars.

Today it is on long-term loan to the Normandy Tank Museum at Catz, near Carentan, where curator Patrick Nerrant hopes to restore and reassemble it in time for the 70th anniversary of the Normandy Landings, in 2014.

• See: Saving A Whale.

History through the lens

S

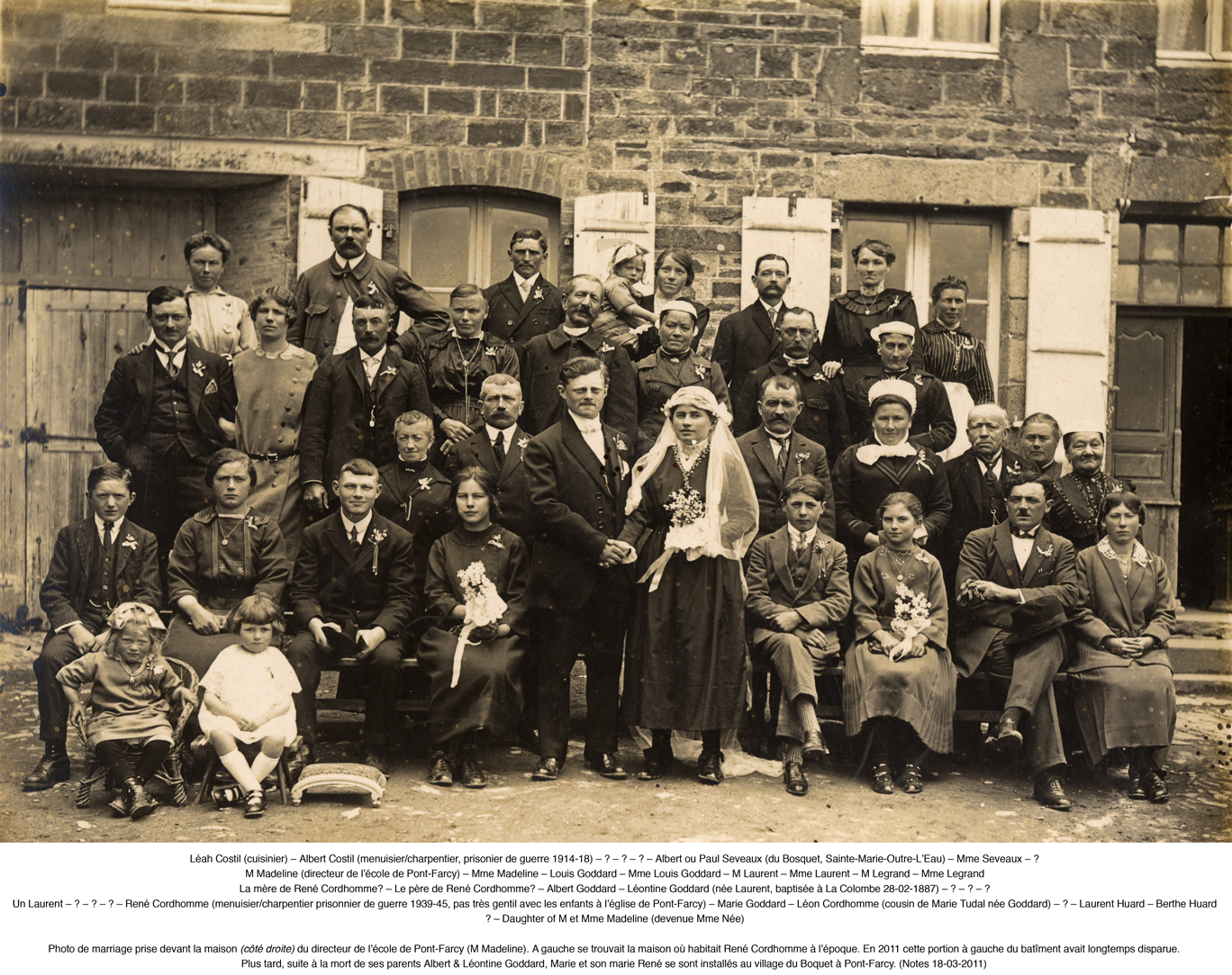

adly we have very few photographs of country people in the Bocage Virois before the Second World War. The population was mostly poor and few people could afford a camera. Of course they all needed a photo for their identity card, so a few would ask the local photographer's studio for a formal portrait while they were there. But for a glimpse of the bocage before and after the First World War we have to rely on the huge numbers of postcards produced and circulated in France depicting town centres, shops and shop-keepers and notable local sights.

Some shopkeepers had pictures taken as they stood proudly in front of their business premises but all these pictures have a static, set-piece look. To see the people of the bocage at their best, however, we have to rely on the standard-issue group wedding photo which was a requirement of any self-respecting bride. Fortunately many families have conserved these family group pictures although they have seldom taken the trouble to record who is who.

In 2010 Christopher Long collaborated with Henri Letellier to present a collection of local marriage photos from the first half of the C20th at the Salle des Fêtes in Pont-Farcy.

• See: The Cordhomme & Goddard family of Le Boquet.

Traditional building materials

C

lay is a wonderful building material. It often lies in the ground where you want to build – and it's free! Mixed with straw, hay, flax or hemp it can form extremely solid and resistant walls with a high insulation efficiency and which are easy to repair and maintain.

This is why it's still in widespread use in some of the world's hottest, coldest, driest and wettest climates. Buildings in Normandy have been built of clay for hundreds – perhaps thousands – of years, particularly in areas such as the marais region where there is no suitable building stone.

But although Pont-Farcy was renowned for its stone quarries, local farmers in the C19th still preferred to build in clay. At this time a great explosion in clay structures in Normandy coincided with the arrival of the dairy industry in the mid-C19th.

Arable farmers generally only needed somewhere to house a horse or oxen – une étable, somewhere to park the plough and harrow, and somewhere to store seed, grain, straw and tools – une grange. When huge numbers of cows arrived, coinciding with the arrival of canals and railways, a whole new range of cheap, well-insulated buildings was required: cowsheds, milking parlours, dairies, barns for hay and straw, housing for veal calves, the bull pen, etc.

Farmers had to build quickly and cheaply and usually did so in a work-group called a corvée. Usually the clay is set on a stone footing about one metre high and two metres of clay could be built in a summer season. Sadly many of these excellent buildings have been abandoned or allowed to decay. Today few people think they're worth restoring – yet building and repairing clay walls is really very simple.

• See: Building with Timber, Straw and Clay.

• See Farm Structures in the Bocage Virois.

The idea of a village

T

he concept of a village in rural Normandy can be confusing. The word derives from the latin villa implying a substantial independent agricultural settlement inhabited by the owner and his family, his servants and his labourers.

In many respects a villa or village implied a fairly self-sufficient community corresponding to the colloquial idea of a manor. In French the words manoir / ménage / mesnil / mas / maison, are closely related. In Normandy un village can also be called a lieu-dit a place with a name.

Following the French Revolution the rural population was supposedly freed from its obligations and bonds to a noble landlord. Theoretically free to set up as subsistance farmers, in practice most were unable to finance the cost individually and so set up groups of three, four or five households sharing certain basic facilities communally. Such small groups of houses are still typical of the Norman countryside.

They usually shared a free-standing bread-oven, a well, a lavoir washing place on a stream, facilities for crushing and then pressing apples, etc. They also shared an address: the name of the village or lieu-dit: e.g. Le Boquet, La Noette or La Fosse. A larger and more prosperous farm didn't need to share facilities communally and often took its name from the family who owned it: i.e. La Sallière belonged to the family Salles and La Clémendière to the family Clémend.

• See: An Archaeological Study of Le Boquet, Pont-Farcy.

Shops and businesses

A

nyone visiting Pont-Farcy today would find it hard to believe that in the early 1960s the town boasted 10 bars and about 40 other shops and businesses, as well as a fire station and a gendarmerie. There were also two blacksmiths, two working mills and four abattoirs.

For food you had a choice between five grocers' shops, two bakers and a charcutier. For clothing you could count on an outfitter, two shoe shops and one draper. From time to time everyone needed one of the two carpenters, the cycle shop and the stone-dresser.

Above right: Many thanks to Jean Delafontaine for the photographs showing his own family's shoe-shop in Pont-Farcy in 1926 and the next-door newsagents and general store owned by the Yver-Prudhomme family and pictured in 1916. These two shops stood exactly opposite the present-day post-office. Below right customers cluster around the garage in Pont-Farcy's high street.

Local farmers still needed the two blacksmiths, the harness-maker and the vet, while all households needed the two hairdressers, the two tobacconists, the ironmonger and the furniture shop. Perhaps the most exciting shop in Pont-Farcy would have been the one selling gleaming new electrical goods.

Electricity had arrived here in 1936, but the mains water supply first reached the town in the 1950s and was being piped out to the farms by 1960 – at last allowing washing machines to replace the itinerant washer-women. Few people had a car in 1960 – though the first tractors were making their appearance – so the one garage was a novelty that would soon displace the stables, the harness-maker and the blacksmiths but which probably made most of its money from traffic passing through.

Pont-Farcy owed its existence to its bridge and the main road linking Paris and northern France with Mont-Saint-Michel and Brittany. A growing number of tourists, car-owners and lorry-drivers would have appreciated the one hotel-restaurant, the roadside restaurant and the ten bars referred to above. In those days drinking and driving often went hand-in-hand, but if drivers became too much of a menace, the town had, as we've seen, its own gendarmerie – and even pompiers ready to pull the inebriated cars out of any ditch.

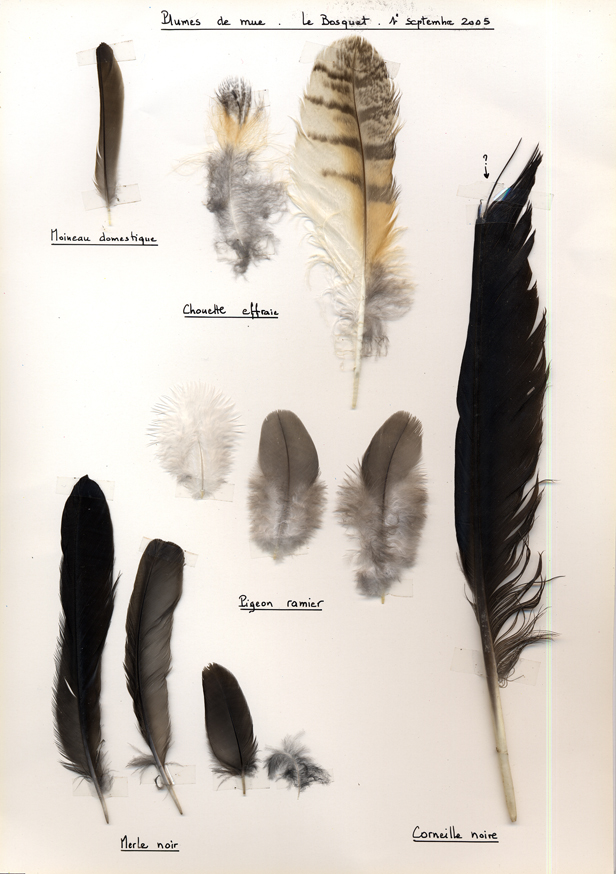

The birds and the bees...

T

he bocage virois should be a wildlife paradise. Famed for its hills, valleys, woodland, hedgerows, streams and lakes, it ought to provide habitats for a wide variety of flora and fauna – especially birds, insects, reptiles and fungi.

However, bigger and bigger farms employing fewer and fewer people have produced industrialised agriculture in France, encouraged by generous farm grants. The drive for production at all costs means that France has less concern for the environmental consequences than most other European countries.

Farming of this sort requires ever bigger fields involving the wholesale destruction of earth banks, hedges and trees. And few natural meadows remain, so the wild plants necessary to amphibians, butterflies and other insects are now rare.

The cereals and maize grown on this prairie landscape are treated with insecticides and anti-fungal sprays which destroy living organisms in the soil. This kills off the lowest levels of the food chain meaning that the middle and upper levels have nothing to feed on either. We very seldom see bees nowadays...

The problem is made worse by the local authorities. They needlessly and expensively mow thousands of kilometres of roadside verges destroying the environment in which plants, insects, small mammals and birds might thrive. Where there are no verges, shrubs or trees there are no nesting sites and no source of fruits and berries to feed birds. Without hedgerows there are no natural 'corridors' allowing birds and small mammals to disperse and meet others with whom to establish territories and mate.

Some parts of the bocage remain healthy. These include abandoned land, woods, old quarries, marshland and steep slopes inaccessible to tractors. But the survival of many species may depend on you and me – anyone, that is, willing to be deliberately 'kind' to their environment on a smallholding or in their garden.

Such 'kindness' can quickly produce positive results. At the small farm of Le Boquet, in Pont-Farcy, monthly bird censuses show that simply by keeping the soil clean and allowing trees and hedges to grow healthily, the number of bird species observed grew from 27 in 2005 to 57 in 2013.

• See: Ornithology

• See: Birds at Le Boquet

• See: L'avifaune du bocage : un exemple à Pont-Farcy

Hedges and hedging

E

nglish landscapes are renowned for their generally dense, thick hedges. These are often well-maintained, replanted from time to time and 'laid' in the traditional fashion. Hedge-laying competitions are widespread in some parts of the country. However, the English appear to have forgotten that they could coppice their hedges in just the same way that they used to coppice woodland. England pays its farmers generously to manage the countryside wisely.

Around Pont-Farcy in the bocage virois local people continue to coppice their hedges, harvesting large quantities of firewood each year. But as the hedges are no longer replanted or maintained, they are usually sad and sparse apologies for a hedge! And the rural craft of hedge-laying, once known as plessage related to the English word 'plaiting' has been entirely forgotten. The English probably 'forgot' about hedge-coppicing when cheap British coal largely replaced wood as a fuel in the C19th.

Similarly, when electricity arrived in the Normandy in about 1936, electric fences replaced hedges for keeping live-stock in their place. Since then, people take what wood continues to grow in the fast disappearing and generally unhealthy hedges that remain. Few think of investing in a hedge. This is a pity because 100 metres of hedge can provide enough wood to heat a small house through a winter about 5-7 cu. metres. One thousand metres of hedgerow, coppiced on a ten or fifteen year cycle, can provide permanent and sustainable household heating.

• See: Hedging

Bridges, fords and stepping-stones

N

early every road and rail bridge in the Bocage Virois was systematically destroyed by the Germans or the Allies in WWll. Famously, a small 'Bull' bridge over the Souleuvre north-west of Bény-Bocage survived because the Germans forgot to destroy it. This gave British tanks the opportunity to make vital advances in Operation Bluecoat in August 1944.

The picture top right shows the C19th lock-keeper's footbridge between Pont-Farcy and Fourneaux in 1913. In August 1944 it was destroyed by the retreating Germans and replaced, after the war, by a 'temporary' British Bailey bridge right which had seen service at Arromanches artificial harbour. This was the bridge saved by Les Amis du Pont Bailey in 2008.

The picture top right shows the C19th lock-keeper's footbridge between Pont-Farcy and Fourneaux in 1913. In August 1944 it was destroyed by the retreating Germans and replaced, after the war, by a 'temporary' British Bailey bridge right which had seen service at Arromanches artificial harbour. This was the bridge saved by Les Amis du Pont Bailey in 2008.

At the same time, American bombers tried and failed numerous times to destroy the stone bridge at Pont-Farcy in order to trap the Germans on the west bank. In the end the Germans simply blew it up when they were on the east bank to prevent the Americans from following them.

Above right is the stone bridge at Pont-Farcy before it was blown up by the retreating Germans in 1944. A day or two later, on 4 August 1944, Pont-Farcy was liberated by American troops sweeping down from St Lô and Tessy. Meanwhile British troops were liberating nearby Bény-Bocage and it may be that a Royal Engineer bridging party laid a temporary British Bailey bridge see below right which remained in place into the 1950s.

A British 'Bailey bridge' not the one now on display close by was quickly put across the gap until it could be repaired, in concrete, in the 1950s. And for a short while in 1944, before the Bailey bridge was in place, the Americans constructed an emergency bridge linking the Tessy road with the old port quay opposite.

In the 1950s many fords survived on country lanes in the bocage, used by carts and livestock, usually with an adjacent stone 'clapper' bridge for pedestrians. Few survive as they were abandoned or destroyed to make way for tractors, or were victims of the remembrements. A rare survivor is at nearby St Aubin-des-Bois see picture right.

In Pont-Farcy there remains a narrow foot-bridge across the Archette stream in the bas du bourg on the path leading to Ste Marie-Outre-L'Eau see picture right. Two massive stones sit on one central stone pillar and in 2001 elderly residents remembered washing pig's intestines here for use as sausage casings.

Another rare survivor is this simple 'clapper' bridge in neighbouring Gouvets see picture right. The ford lies across a footpath, due west of Gouvets mill, but there are signs that the single span clapper bridge may have been displaced, perhaps to make room in the ford for the width of a tractor.

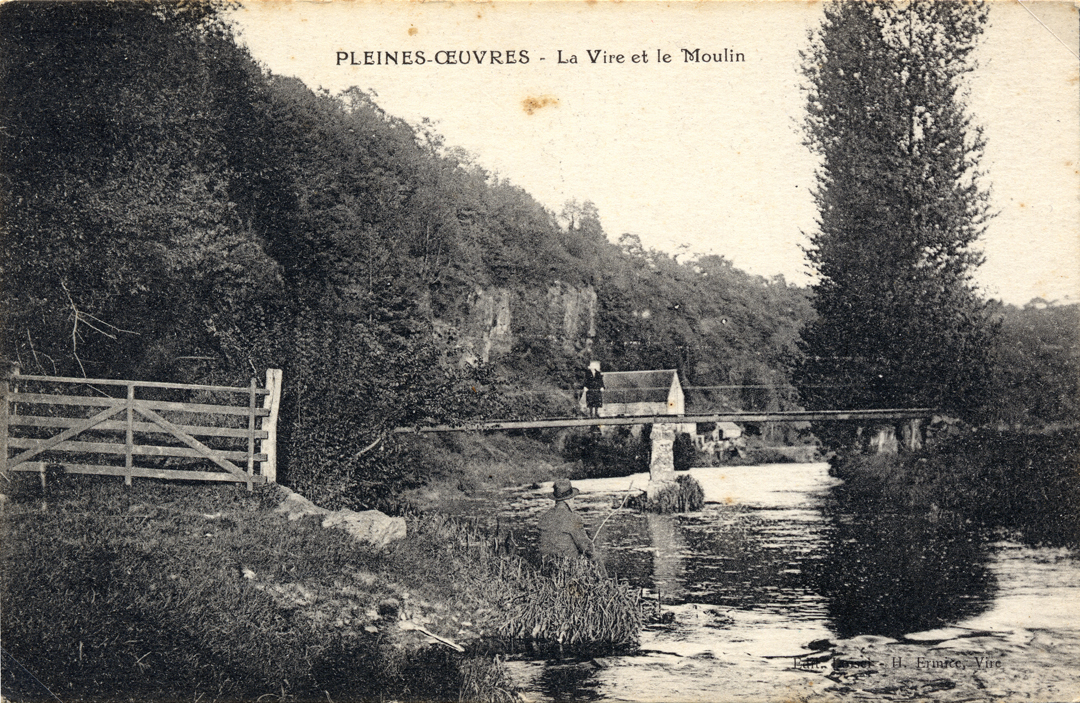

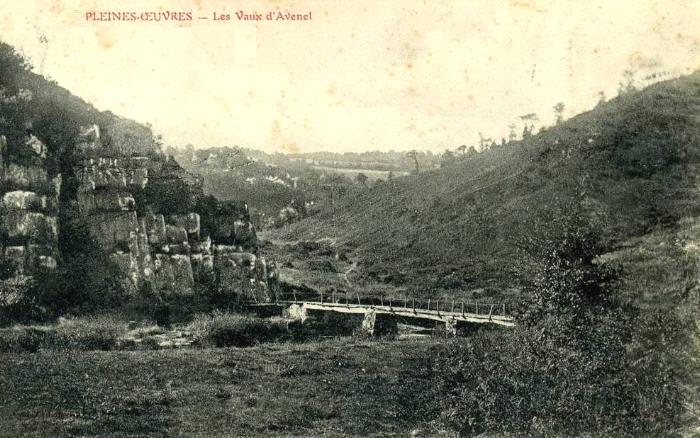

Pictured below right is the footbridge which once linked Pleines-Oeuvres with Ste-Marie-Outre-L'Eau. The footings of this bridge are still visible on either side of the Vire.

Below: Two views of the Planches d'Avenel which linked Pleines-Œuvres and Bures-les-Monts with Pont-Bellanger. Such footbridges probably typical of others that have now disappeared. Note the lunar landscape of the Vire gorges. These ravaged hillsides, now covered in trees, are probably the result of sheep grazing.

• See: Clapper Bridges in the Bocage

• See: Saving a Bailey Bridge

Baraquements: Emergency Housing in 1944

A

s the Battle of Normandy rumbled across Normandy in June, July and August of 1944, the destruction it left in its wake was catastrophic.

Ninety per cent of St Lô was destroyed and 80 per cent of Vire...

Many towns like Estry and Villers-Bocage were almost wiped off the map. A handful of important towns were left largely unscathed: Villedieu-les-Poëles and Bayeux, for example. But thousands of houses were destroyed and tens of thousands found themselves homeless.

Some stayed with relations but many were housed in temporary wooden hutments. These simple structures gave many rural families in Normandy – accustomed to living, eating and sleeping in just room – their first taste of comforts long taken for granted in Britain and the USA.

These pre-constructed modular buildings were imported from Canada, Scandinavia and from France herself. They could be assembled to form houses, shops and even salles des fêtes. Seventy years later only a handful of these timber buildings had survived (see slide show).

Mostly they had been moved from their original locations and reassembled to form workshops or garages although St Fromond still had one in its original location. At Pont-Farcy two examples were visible in 2013: one being a garage beside the Route de Montabot.

The other consists of the remains of the former salle des fêtes from Vaudry, near Vire, which in 1945 replaced the original salle des fêtes destroyed in 1944. In the 1980s it was moved and reassembled at Le Bosquet, near the Route de Montbray.

• See: Reconstruction of Vire after World War ll

• See: Baraquements: Temporary hutments for wartime homeless

An artisan iron industry in Pont-Farcy ?

• See: Iron In The Bocage Virois ?