Artisan Iron Working

in the Valleys of the River Vire?

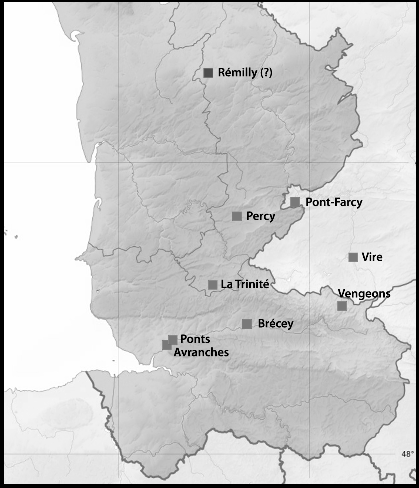

The author believes that from at least the C11th an important artisan iron-working 'industry' existed in the thickly wooded, iron-rich valleys of the river Vire basin at Pont-Farcy in Normandy and indeed along a narrow geological band from around Percy in eastern Manche to Le Plessis Grimoult in Calvados.

The author believes that from at least the C11th an important artisan iron-working 'industry' existed in the thickly wooded, iron-rich valleys of the river Vire basin at Pont-Farcy in Normandy and indeed along a narrow geological band from around Percy in eastern Manche to Le Plessis Grimoult in Calvados.

by Christopher Long

The pre-requisites for the existence of an artisan iron industry at least as early as the mediaeval era include:

- Easily accessible iron-rich ore in sufficient quantity and of adequate quality

- A sustainable supply of timber as a reliable source of charcoal

- A ready supply of clay in order to make furnaces

- A local need for iron or its products and/or the ability to export it

- A market through which iron or its products could be sold

- The organisational ability to finance, extract, process and market iron

In the map above, the areas marked in chestnut brown (BRGM K O1) consist of vivid red rocks and soil stretching from near Percy (Manche) to the river Odon south of Caen (Calvados). Below, iron slag found by an amateur achaeologist at La Ferrerie, Pleines-Oeuvres, and identified in December 2015 by the author who had been hoping to find precisely this sort of debris at precisely that spot! The material has vitrified, suggesting it was the product of a 'bloomery', probably dating from the some time after the C14th.

If the pre-requisites for an artisan iron industry can be shown to exist (see below), the following are indicative of the existence of an artisan iron 'industry' in the Bocage Virois:

- The discovery of iron slag at sites with iron-related toponyms

- The presence of an unnaturally disturbed landscape typical of surface mineral extraction close to iron-related toponyms

- A persuasive number of local iron-related toponyms either in close proximity or extending along a defined geological structure

- The apparent use made of Domjean Priory by the monks of Mont Saint-Michel

- The foundation or confirmation of Villedieu (Manche) as a metal market by the Comte de Coutances (later King Henry l, Duke of Normandy)

- A still-visible industrial heritage in the Bocage Virois

- The Pont-Farcy clock-makers of the XVlllth and XlXth centuries

- The land holdings of the Mesnil-Guérin (Mainwaring) family

- The hydraulic power of the river Vire and, notably, its tributaries

Iron toponym clusters

The 'Pleines-Oeuvres' cluster

- Fervaches ('iron ------' meaning uncertain)

- Fourneaux (furnaces)

- La Ferrerie, Pleines-Oeuvres (iron works)

- La Haute Ferrière, Pleines-Oeuvres (upper iron works)

- Gatefer, Beuvrigny ('iron way' or 'way to the iron')

- La Hatuyère, Pont-Farcy (La Haute Tuyère – a tuyère being a construction used to funnel air into a 'bloomery' furnace)

- La Crière (corruption of carrière? The same toponym occurs at Beuvrigny, Pont-Farcy, Ste Marie-Outre-L'Eau, Campeaux, Ste Marie-Laumont and Le B´ny-Bocage. Some of these presumably supplied building stone. La Crière at Beuvrigny appears to be iron-related)

Very similar complicated rock structures seem to exist at various places along a 15 km stretch along the eastern bank of the river Vire – e.g. on the slopes between Domjean, Troisgots and La Chapelle-sur-Vire (north of Tessy) and along parts of the Vire valley gorges between Pont-Farcy and Bény-Bocage. Until a geological study takes place it is not possible to say which rocks (probably sandstones) might have been exploited by any iron-smelters in these areas. Unsurprisingly however, we find clusters of iron-related toponyms elsewhere in Calvados, Orne and Manche:

The Bocage Virois cluster

- Fervaches (Manche)

- Fourneaux (Manche)

- Les Ferrières (Tessy, Manche)

- La Ferrerie (Pleines-Oeuvres, Calvados)

- La Haute Ferrière (Beuvrigny, Calvados)

- La Hatuyère (Pont-Farcy)

- Gatefer (Beuvrigny, Manche)

- La Tailleferie (Domjean, Manche)

- La Forge (Pont Bellanger, Calvados)

- La Ferrière-Harang (Calvados)

- La Ferronière (Bény-Bocage, Calvados)

- La Forge (Beaulieu, Calvados)

Other clusters in Calvados

- La Ferrière-au-Doyen * (Saint Martin-des-Besaces, Calvados)

- La Ferrière-Duval [du Val] (Le Plessis-Grimault, Calvados)

- Danvou-la-Ferrière (Aunay-sur-Odon, Calvados)

- Château de la Ferrière (Vaux-sur-Aure, Calvados)

- Fourneaux (Cahan, Calvados)

- La Ferrière-sur-Risle (Lisieux, Calvados)

- La Ferronnière (Moyaux, Calvados)

- La Forge (Moyaux, Calvados)

- Fervaques (Calvados)

- Fourneville (Calvados)

- Fourneaux-le-Val (Calvados)

Clusters in Orne:

- La Mine de la Ferrière-aux-Etangs (Orne)

- La Ferrière-Bochard (Orne)

- La Ferrière-Béchet (Orne)

- La Ferrière-au-Doyen (Orne)

- Glos-la-Ferrière (Orne)

- Fourneaux-le-Val (Falaise, Orne)

- La Ferronnière (Putanges, Orne)

- La Ferronnière (Neauphe-sous-Essai, Orne)

- La Ferronnière (Landigou, Orne)

- La Ferté-Macé (Orne)

- La Ferté-Frênel (Orne)

- Ferrières-la-Verrerie (Orne)

A cluster in the Sarthe:

- La Ferté-Bernard (Sarthe)

Clusters in Manche

- La Ferrière (Pierreville, Manche)

- La Forge (Pierreville, Manche)

- La Ferrière (Surtainville, Manche)

- Ferrières (Mortain, Manche)

- Fermanville (Cherbourg, Manche)

Elsewhere in France

- Gatefer (Saint Trivier-sur-Moignans)

- Gatefer (Courzieu)

- Rue de Gatefers (Yzeures-sur-Creuze)

- Rue de Gatefer (Cosnes-Cours-sur-Loire)

- Chemin de Gatefer (Saintes)

- La Ferrerie (Angey)

- La Ferté-sous-Jouarre (Seine-et-Marne)

- La Ferrerie (Beaufay)

- La Ferrerie (Buais)

- La Ferrerie (Le Pas)

- Ferrières-en-Bray (Seine-Maritime)

- Ferrières-en-Brie (Seine-Maritime)

- Ferrières-en-Gâtinais (Loiret)

- Fourneaux (Loire)

- Fournes-en-Weppes (Nord)

- Fournival (Oise)

- La Ferrière (Côtes-d'Armor)

- La Ferrière (Indre-et-Loire)

- La Ferrière (Isère)

- La Ferrière (Vendée)

- La Ferrière-Airoux (Vienne)

- La Ferrière-de-Flée (Maine-et-Loire)

- La Ferrière-en-Parthenay (Deux-Sèvres)

- La Ferrière-sur-Risle (Eure)

- Ferrière-et-Lafolie (Haute-Marne)

- Ferrière-la-Grande (Nord)

- Ferrière-la-Petite (Nord)

- Ferrière-Larçon (Indre-et-Loire)

- Ferrière-sur-Beaulieu (Indre-et-Loire)

- Ferrières (Charente-Maritime)

- Ferrières (Meurthe-et-Moselle)

- Ferrières (Oise)

- Ferrières (Hautes-Pyrénées)

- Ferrières (Somme)

- Ferrières (Tarn)

- Ferrières-en-Bray (Seine-Maritime)

- Ferrières-en-Brie (Seine-et-Marne)

- Ferrières-en-Gâtinais (Loiret)

- Ferrières-Haut-Clocher (Eure)

- Ferrières-le-Lac (Doubs)

- Ferrières-les-Bois (Doubs)

- Ferrières-lès-Ray (Haute-Saône)

- Ferrières-lès-Scey (Haute-Saône)

- Ferrières-les-Verreries (Hérault)

- Ferrières-Poussarou (Hérault)

- Ferrières-Saint-Hilaire (Eure)

- Ferrières-Saint-Mary (Cantal)

- Ferrières-sur-Ariège (Ariège)

- Ferrières-sur-Sichon (Allier)

- Fourneaux (Loire)

- Fourneaux (Savoie)

- Abbaye de Fervaques (Aisne)

- Clermont-Ferrand (Auverne)

H

alf way between Pont-Farcy and Tessy-sur-Vire, on the east bank of the river Vire, five iron-related toponyms occur in an entirely rural context within a radius of half a kilometer of each other. A sixth lies two kilometres away at Tessy and the village of Fervaches provides a seventh, three kilometres away.

A cluster of iron-related toponyms almost certainly indicate the presence of iron working, but alone they provide no evidence of iron production. Where, however, the cluster occurs on a pocket of land that is known to be rich in iron-bearing ore (which may turn out to be the case on the Fourneaux/Pleines-Oeuvres boundary) it becomes possible to argue that iron extraction and smelting took place there.

The Pleines-Oeuvres cluster

- Fervaches (meaning uncertain)

- Fourneaux (furnaces)

- La Tailleferie, Domjean (iron-related coppice?)

- La Ferrerie, Pleines-Oeuvres (iron works)

- La Haute Ferrière, Pleines-Oeuvres (upper iron works)

- Gatefer, Beuvrigny (iron 'way' or 'wasteland')

- La Hatuyère, Pont-Farcy (the 'haute/high tuyere', a tuyere being the jet-like construction used to funnel air into a mediaeval 'bloomery' furnace)

- La Crière, Beuvrigny (a corruption of carrière? The same toponym occurs at Beuvrigny, Pont-Farcy, Ste Marie-Outre-L'Eau, Campeaux, Ste Marie-Laumont and Le Bény-Bocage. Some of these presumably supplied building stone. La Crière at Beuvrigny appears to be iron-related)

The sites are located at a point where the river Vire cuts deeply through a great ridge of hills running diagonally across Calvados and Manche and for convenience they will be called the Pleines-Oeuvres cluster, lying on either side of a tributary of the Vire called Le Tison, the rock and soil on whose southern side is coloured a deep red. Furthermore, the toponyms relate to settlements which appear to be associated with small valleys flowing north into the Tison stream: e.g. Gatefer, La Crière, La Ferrerie, and La Haute Ferrière.

The river Vire has created about 25 kilometers of tortuous gorges with steep cliffs between Les Roches de Ham in the north and Sainte Marie-Laumont in the south.

These slopes and the surrounding valleys are usually thickly wooded with coppice timber (ash, chestnut, hazel, oak, etc) while the most exposed rock faces have for many centuries been quarried for building stone which was transported by river (from 1861 by canal) to St Lô and beyond.

In every respect the Pleines-Oeuvres cluster of toponyms is perfectly situated for iron extraction. Rocks and soil in these precise areas are notably red (indicating a rich iron content) but it has yet to be established from geological study which stone (presumably a sandstone) would have attracted iron-smelters. The surrounding coppiced hillsides would have produced copious quantities of sustainable charcoal and the river margins, like much of the surrounding countryside, are rich in the clay/sediment necessary for building furnaces.

Smelting requires water, especially if water-powered bellows are used to pump air through a tuyere into the furnace. Not surprisingly the Pleines-Oeuvres cluster sites are situated beside the Le Tison. This apparently insignificant stream is specifically named on the early C18th map by G. Mariette de la Pagerie when almost every other similar stream is left unnamed.

[A Roger Tison of Domjean is named in the cartulary of Mont Saint-Michel, ca.1155. He had dealings with abbot Robert de Torigni who was himself born in Tessy and seems to have taken a close interest in the affairs of neighbouring Domjean priory.]

The Tison stream appears to have its source in Beuvrigny and the G. Mariette de la Pagerie map (1690 / 1720) clearly marks a mill associated with a mill-pond which survives to this day near Gatefer. Such a mill might have served the needs of iron-smelters and there is also clear evidence of elaborate water management (leats, sluices, etc) along most of the Tison stream whose purpose it is difficult to explain. The 'Tison' stream, along which are several iron-related toponyms, is a tributary of the river Vire which would have provided a means of importing materiels and exporting products.

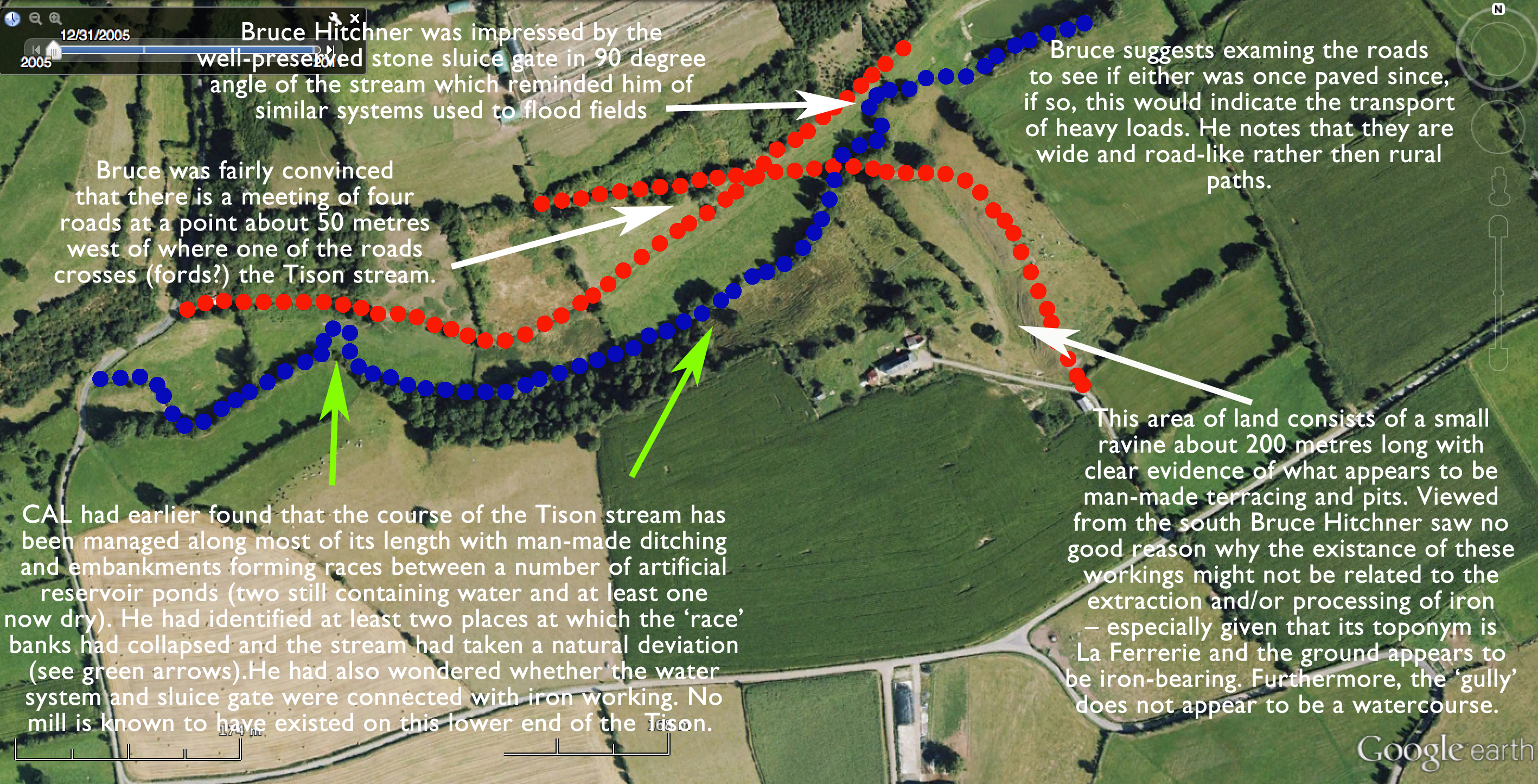

In the map above, the dotted lines mark small valleys which, along with the Tyson valley itself, the author believes may have been involved in iron extraction or smelting.

If this area was indeed a source of iron ore, it was not necessary to mine into the ground to recover it because the steep hillsides and the Vire valley gorges permit surface quarrying.

From at least the Xllth century, the nearest small centres of population would have been Pleines-Oeuvres (on the heights above the eastern end of the bridge at Pont-Farcy, two kilometers upstream) and Pont (on the eastern end of the bridge at Tessy, two kilometers downstream), then held by the Prior of Domjean.

In August 2015 the author was accompanied by Prof. Bruce Hitchner (classicist and historian at Tufts University) on a walk up the Tison stream, followed by a visit to the La Ferrerie site. His observations were very useful and some are recorded in the notes in the image above.

It has yet to be established who owned the Fourneaux cluster land in the Xllth century. It may well have formed part of the estates of the Prior of Domjean, but, if not, it almost certainly belonged to the prior's neighbours, the Mesnil-Guérin family (later the Farcy family), who held most of the surrounding land at Beuvrigny, La Chapelle-Heusebroq, Sédouy, Pont-Farcy (then known as St Jean de Mesnil-Guérin) and Ste Marie Outre-L'Eau (then known as Ste Marie de Mesnil-Guérin).

[The author is most grateful to historian Dominique Doublet whose study the Mesnil-Guérin and Farcy families has been most helpful. D. Doublet explains that the Guérin family also held inter alia the manors of Le Mesnil Ceron near Percy, and Le Chêne Guérin near Gouvets. He has also shown that during the Xllth century the Farcy family acquired by marriage many, if not most, of the Guérin estates and gave Pont-Farcy its name when a stone bridge was constructed there. Members of the Mesnil-Guérin family settled in England following the Conquest where their name became Mainwaring or Mannering.]

Though it remains unclear whether the Pleines-Oeuvres cluster land belonged to Domjean Priory or to the Guérin family, it is nevertheless the case that an influential and well-organised lord would have been needed to exploit this natural resource, handling every aspect of the operation from investment in water courses, mills and furnaces to the management of woodland, ore extraction, transport and marketing.

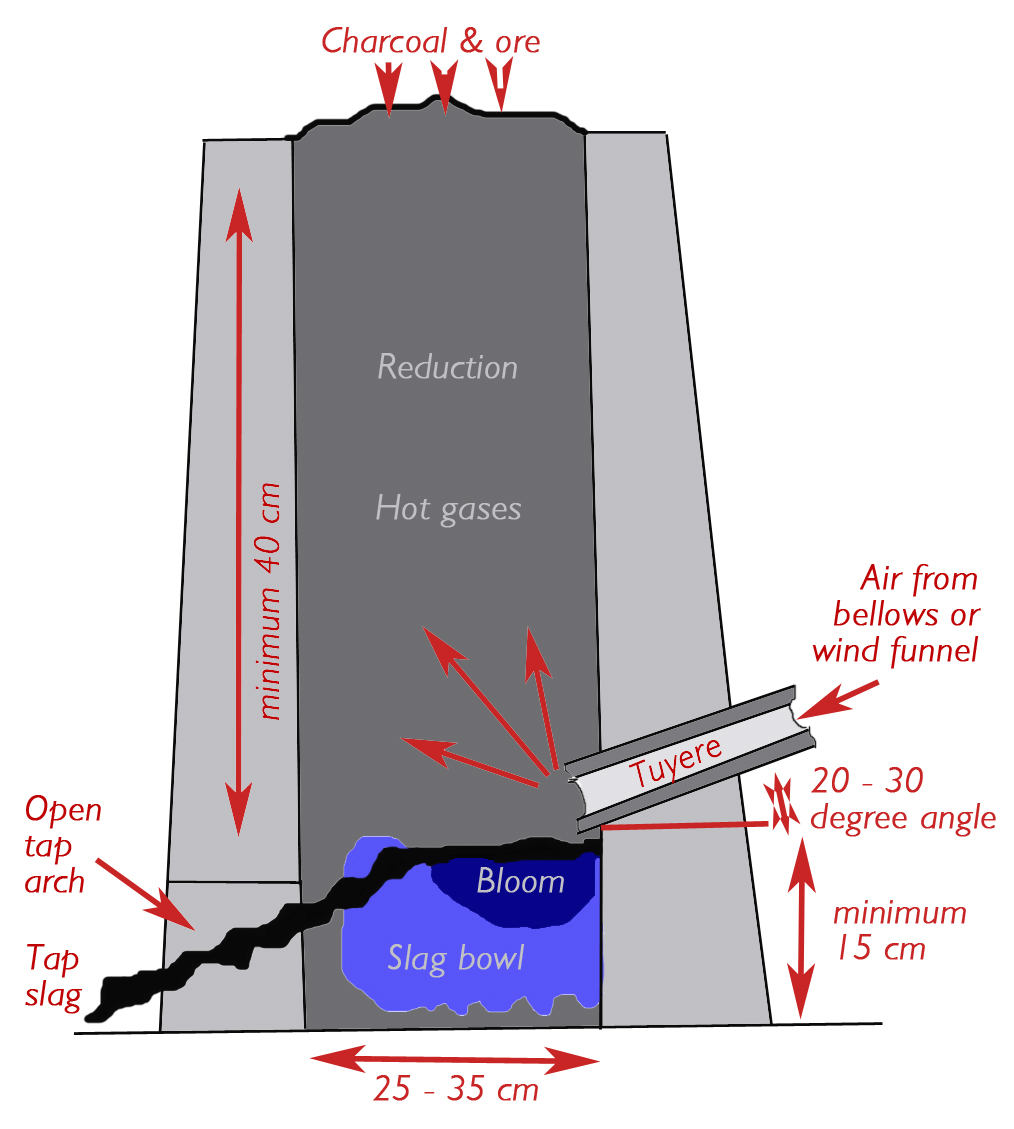

In addition to obtaining and granting mineral rights, skilled men would have been needed to build and operate the bloomery furnaces and further teams would have been needed to quarry and prepare the stone for smelting which may have involved two or three smelting phases to achieve pure iron. In this regard, the author wonders whether secondary and tertiary smelting took place at La Hatuyère on the heights across the river in Pont-Farcy.

In addition to obtaining and granting mineral rights, skilled men would have been needed to build and operate the bloomery furnaces and further teams would have been needed to quarry and prepare the stone for smelting which may have involved two or three smelting phases to achieve pure iron. In this regard, the author wonders whether secondary and tertiary smelting took place at La Hatuyère on the heights across the river in Pont-Farcy.

The author is greatly indebted to the industrial archaeologist Robert Waterhouse FSA who not only suggested that the Hatuyère name might be associated with the tuyere used in furnaces, but who was also able to describe various structures specifically used on exposed hill-tops in order to channel wind into the base of the furnace chamber.

SEE WIKIPEDIA: "A tuyere or tuyère is a tube, nozzle or pipe through which air is blown into a furnace or hearth. The term (like many technical terms relating to ironmaking) was introduced to England from French with the new technology of the blast furnace and finery forge in around 1500, and was sometimes anglicised as tu-iron. A bloomery normally had one tuyere... Early blast furnaces also had one tuyere, but was fed from bellows perhaps 12 feet (3.7m) long operated by a waterwheel. During the Industrial Revolution, the blast began to be provided using steam engines... The blacksmith's hearth at their forge has a tuyere, often blown by foot-operated bellows. Tuyeres were also used in smelting lead and copper in smeltmills."

The furnaces would have consumed great quantities of fuel and so communities of charcoal-burners would have worked the woodlands on a cyclical basis, coppicing one area and then moving on to the next. The iron smelters too may have needed to move from place to place in order to harvest the richest and most accessible surface iron ore. It is believed that iron-workers in England in the Xllth century (e.g. in the Weald of Kent) collaborated in a well-coordinated, peripatetic manner. No doubt iron smelting in Xllth century Normandy was a similarly mobile woodland activity.

Finally, the iron itself would have been transported, probably on shallow river punts, to a warehouse and then carted to a regional metal market such as Villedieu. And since iron was an extremely valuable commodity, guards would have been needed at every stage to ensure its safety.

N.B. The toponym 'Gatefer' may be significant to understanding the way the Pleines-Oeuvres cluster land was used. The Old Norse (viking) word 'gata' means a 'path or lane' – i.e. gatefer = ironpath and also appears in names such as Gatwick. This is the likely meaning in the Pleines-Oeuvres cluster. By extension, '-gate' can also mean harbour (e.g. Houlegate, Sangatte, etc). NB: in Normandy 'gate/gâté or 'gaste' can also mean 'spoil' or 'waste', as in 'wasteland' (e.g. Terregate, Le Gast, Gathemo and the maritime word for waste: gash).

In the last case, gaste or gâche in Norman becomes waste in English in the same way that Guillaume becomes William. (See also: guichet-wicket, guerre-war, guerrier-warrior, gagne-win, guêpe-wasp, guardien-warden, garderobe-wardrobe, Galles-Wales, gage-wage, garble-warble, guarantie-warranty, garenne-warren and similarly guile/wile, guise/wise, guard/ward, etc.)

See Pawlowski's Normandie Inconnue (1911)

The true value of Domjean

In 1015 Countess Gunnora makes a gift of Domjean to the abbey of Mont Saint-Michel. The witnesses were the bishops of Coutances, Bayeux, Sées, Avranches and Lisieux and about thirty other dignitaries. The land was alleus, i.e. hereditary property in return for non-military services. The historian David Nicolas-Méry has pointed out that the monks of Mont-Saint-Michel appear to have placed a great value on the forests that formed a large part of their estates around and beyond the Bay of Mont-Saint-Michel.

When Countess Gunnora gave the manors of Domjean and Bretteville-sur-Odon to the monks of Mont Saint-Michel these must have been gifts as generous as any made by a great ruler. It must have been worth a lot if the monks had to travel 72 km to deliver its revenues.

The author suggests that the Xlth century main road from Caen to Avranches via Villedieu may have used the Domjean-Tessy river crossing at Pont – until the Farcy family built a new stone bridge at Pont-Farcy in the Xllth century.

T

he manor of Domjean had formed part of the dowery of the Countess Gunnora (sometimes called Gonnor, c.950 - c.1031), wife of the Norman ruler Count Richard l. She is known to have been rich in her own right and to have been a powerful figure in Norman affairs, sometimes even described as regent of Normandy.

Following the death of her husband she made gifts of the manors of Domjean and of Bretteville-sur-Odon (Britaville) to the abbey of Mont Saint-Michel. She did this for benefit of Duke Richard's soul, her own soul and that of her sons "Count Richard, archbishop Robert and others". However, the gift was made in 1015, nineteen years after Richard's death, and so perhaps the good of her own soul was uppermost in her mind.

Although we know little more than this, the gift of Domjean must nevertheless have been generous and valuable. It needed to be a gift worthy of a ruler's widow seeking God's mercy for the souls of her husband, her sons and herself. Earlier in her life she had founded Coutances cathedral and so, in contemplating the after-life, she would surely have wanted the monks of Mont Saint-Michel must to receive something at least as valuable as a cathedral.

The obvious question is: in what did the value and worth of Domjean consist? And the answer is we don't know.

We only know that it was described as a priory, that it was 72 kilometers from it mother abbey at Mont Saint-Michel (and thus one of the farthest-flung of the abbey's priories if you exclude Otterton in Devon and St Michael's Mount in Cornwall).

We also know that an intriguing toponym La Priorté exists to this day, perhaps the site of the original priory buildings, but more significantly a large, fairly flat area of land on a defensible headland. There it dominates and might once have controlled the river-crossing below.

This river-crossing (today a bridge) lies between Tessy on the western flank of the river Vire and Pont (part of La Priorté and Domjean) on the eastern flank.

What makes the story still more mysterious is that the priory itself was apparently 'abandoned' in around 1180 although its surrounding parishes (e.g. Fourneaux and Beuvrigny) were retained.

The author is currently pursuing four hypotheses:

- That the real value of Gonnor's estate at Domjean consisted in its iron and timber. (Quite incidentally, she is said to have been the daughter of a forester.)

- That the monks of Mont Saint-Michel may at first have tried managing the estates for their iron revenues but by 1180 had (perhaps progressively) farmed out the lands and 'industry' to others.

- That this explains how the Mesnil-Guérin family became lords of the manors of Beuvrigny and Fourneaux (rich in iron) by the Xllth century – these same lands being acquired by marriage by the Farcy family later in the Xllth century.

- That the Vire river crossing at Pont, between Domjean and Tessy, had great strategic important and earned valuable revenues in the Xth and Xlth centuries – perhaps providing the sole crossing point on the principal Caen—Torigni—Tessy—Villedieu—Coutances—Avranches axes. But that the priory at Domjean lost these revenues when the Farcy family built their own stone bridge at St Jean de Mesnil-Guérin – thereafter called Pont-Farcy – and so established a new Caen—Pont-Farcy—Villedieu—Coutances—Avranches axes.

See the remarkable work of Dominic Doublet: copies in the Archives Départementales de la Manche, Saint-Lô.

À sa mort en 1087, Guillaume le Conquérant partage son héritage entre ses trois fils : Robert Courteheuse, l’aîné, reçoit la Normandie, Guillaume Le Roux, le second, l’Angleterre et le plus jeune, Henri, la coquette somme d’argent de cinq mille marcs.

Dès 1088, Robert Courteheuse veut reprendre l’Angleterre et s’endette auprès de Henri qui reçoit en échange le Comté de Coutances, c’est-à-dire presque toute la Manche, sauf le comté de Mortain.

C’est dans cette période qu’il fait construire les châteaux de Vire, Gavray, Pontorson et le donjon de Coutances. Il soutient une école à Avranches et est considéré comme un esprit vif, versé dans les lettres et les sciences. C’est pour cette raison qu’il est surnommé Beauclerc.

T

he town of Villedieu was originally founded as a recycling centre and as a market for metals in around 1126-1130 by King Henry l of England (youngest son of the Conqueror and also Duke of Normandy).

Henry rewarded the loyalty of the Knights of St John of Jerusalem by giving them the town and the revenues of this lucrative metal trade. In return, the knights (later the Knights of Malta) protected the roads and pilgrim routes in the direction of Mont Saint-Michel from their commanderie headquarters in Villedieu.

Presumably Villedieu market traded in the commonly used metals of the day – iron, copper, lead and tin – as well as recycled alloys such as pewter and bronze, thus giving rise to an artisan tradition of bronze, pewter and copper-working which survives to this day. However, the fact that Henry granted a charter to the Knights of St John does not necessarily mean that a metal market was thus created. It is very likely that such a market already existed and that this charter simply asserted Henry's authority, confirming the status of the town as a market and assigning the privileges to the Knights. Such Norman charters (i.e. confirming a status quo ante) are common in the 11th and 12th centuries.

The location chosen for this market is interesting:

- Villedieu lies conveniently on the direct road-line linking Rouen and Caen with the most westerly frontier of the Duchy of Normandy at Avranches and Mont Saint-Michel (via Pont-Farcy and Tessy).

- The town lies in a valley surrounded by thickly wooded hillsides capable of providing copious quantities of timber and charcoal for furnaces, as well as deep valleys and the fast flowing tributaries of the river Sienne which would have provided power for numerous mills.

- At the time of its foundation in the early 12th century, Villedieu lay at the heart of the area (known today as Manche and western Calvados) which William the Conqueror and his father had captured for Normandy from occupying Breton settlers. In such favourable circumstances, the Bretons had almost certainly long been engaged in iron-smelting and metal working by the time Henry l formalised the arrangements in Villedieu in feudal terms.

- While iron was undoubtedly available locally, tin (from Cornwall and Brittany), lead (from Devon) and copper (from England, Wales and Scandinavia) would have been imported. The historian and archaeologist Daniel LEVALET agrees that in mediaeval times flat-bottomed barges, towed by teams of men or animals, would have been able to navigate the river Sienne from the coast at Regneville as far inland as Villedieu.

- This particular region of Normandy was already familiar to Henry l. From around 1088 he became Compte de Coutances (in return for loans to his brother Robert) and so controlled almost all of the Manche region except the 'county' of Mortain. Villedieu lay near the heart of the 'county' of Coutances. Significantly, at this period Pont-Farcy and the iron-rich hills bordering the basin of the river Vire also lay within the jurisdiction of Coutances even though today Pont-Farcy lies in the see of Bayeux and belongs to Calvados. If Henry l had already benefitted from the wealth-generating market in metals in Villedieu from 1088, it is hardly surprising that he granted such a valuable prize to the prestigious Knights Hospitallers, the most famous of the Christian military orders of the Middle Ages.

- Regarding the market for iron in the Cotentin in the mid-C16th, Julien DESHAYES makes the interesting point that Squire Gilles de Gouberville records that he had two principal sources of iron. For small ad hoc needs, men would smelt small quantities of iron on the Squire's own land. If however a large amount was needed (e.g. nails, bolts, ties, brackets, locks, hinges, etc., for a new building), he would go to a forgeron capable of supplying a range of finished products.

NB: The name Villedieu-les-Poëles was invented for tourism and marketing purposes in 1926!

From: Richard CHAVIGNY

Subject: Horloges lanternes

Date: 23 Jul 2014 12:31:27 GMT+2

To: Christopher Long

Cher Monsieur Long

Suite a notre conversation téléphonique j'ai recherché dans mes archives et j'ai relu des texte qui correspondent très bien à la piste que vous m'avez indiqué.

On retrouve souvent dans l'histoire de la fabrication des premières horloges les mêmes conditions: dans un lieu ou il y a du fer facile à récupérer (zones d'affleurement de minerai) du bois qui est transformé en charbon de bois et une rivière pour fournir la force hydraulique. Les paysans lors de leurs moments perdus les utilisent pour fabriquer des instruments aratoires élémentaires comme les socs de charrue, des outils simples comme les serpettes, des clous pour ferrer les chevaux, puis des armes de chasse, certains en font un métier et fabriquent des serrures, d'autres font des armes à feu et un beau jour on leur demande de faire une horloge. Mais ce n'est pas une industrie on fait une horloge à la demande. Ce n'est que un peu plus tard à Morez et ses alentours et dans le sud de la Foret Noire que petit à petit ces travaux passent du stade artisanal au stade semi-industriel.

Ces conditions sont réunies dans le district des Franches Montagnes dans le Canton du Jura en Suisse Alémanique; en Lorraine du coté de Montmédy, en Auvergne, en Catalogne (grâce aux célèbres forges catalane) et donc en Basse Normandie du coté de Pont-Farcy.

Tout ceci parait logique voici donc un premier pas vers ce qui peut être la réalité, mais il reste pas mal de pas à faire dans cette direction.

Avec toutes mes amitiés.

Richard

O

ver the past three or four hundred years only clock-making has brought Pont-Farcy any renown or any attention from historians and academics.

Pont-Farcy clocks are Norman versions of the ubiquitous 'lantern' or 'bracket' clocks which were made famous by English makers in the reign of Queen Elizabeth l and widely exported, notably to the Low Countries and to Caen.

Such clocks were copied in France and throughout Europe and were later enclosed in wooden boxes – largely to protect them from dust – to become 'long-case' clocks. The job of making the cases, of course, was out-sourced to cabinet-makers.

Such clocks were copied in France and throughout Europe and were later enclosed in wooden boxes – largely to protect them from dust – to become 'long-case' clocks. The job of making the cases, of course, was out-sourced to cabinet-makers.

Pont-Farcy's association with clock-making is well attested and a number of 'Pont-Farcy' clocks from the C17th and C18th survive, along with the names of some of their makers.

Among these are: 'François Le Marchand Aîné à Pont-Farcy', 'Alexandre à Pontfarcy 1750', 'Bunel F.A. Pont-farcy', 'Bunel A Pont-farcy (1750)' and in the early C19th 'Lemarchand Alexandre Pont-farcy'.

Among these are: 'François Le Marchand Aîné à Pont-Farcy', 'Alexandre à Pontfarcy 1750', 'Bunel F.A. Pont-farcy', 'Bunel A Pont-farcy (1750)' and in the early C19th 'Lemarchand Alexandre Pont-farcy'.

The best recent study of Pont-Farcy clocks is that of David NICOLAS-MÉRY who in Horlogerie vernaculaire bas-normande states that, regardless of where they were actually made, the generic term for a lantern clock of this period in Lower Normandy is 'de Pont-Farcy'.

Clock components were certainly made in Pont-Farcy, but it is less certain that they were always assembled there. As Richard CHAVIGNY says, it is likely that artisans in Pont-Farcy supplied components to other clock-makers in the region and to makers in large towns such as Caen.

Clock components were certainly made in Pont-Farcy, but it is less certain that they were always assembled there. As Richard CHAVIGNY says, it is likely that artisans in Pont-Farcy supplied components to other clock-makers in the region and to makers in large towns such as Caen.

Charcoal

This photograph of charcoal burners, in the forests of the former abbey at Saint-Sever, Calvados, must have been taken shortly before, or soon after, WWl.

Life for these itinerant woodland artisans in the C20th was gruelling and had probably not changed much in the 900 years since their forebears were doing just the same work in the forests of Domjean Priory, about 22 kms away.

Their work involved coppicing woodland on a cyclical basis, stacking the wood in great piles or 'clamps' covered with clay or turf and burning it slowly in the absence of oxygen. This resulting charcoal was used to extract iron from iron-ore and made iron forging possible since charcoal burns at intense temperatures (up to 2,700°C) whereas iron melts at 1,200-1,550°.

Their work involved coppicing woodland on a cyclical basis, stacking the wood in great piles or 'clamps' covered with clay or turf and burning it slowly in the absence of oxygen. This resulting charcoal was used to extract iron from iron-ore and made iron forging possible since charcoal burns at intense temperatures (up to 2,700°C) whereas iron melts at 1,200-1,550°.

Charcoal burners usually lived in rudimentary woodland huts, often made of stacks and clay, and the work was potentially very dangerous since the burning process produces methane. In mediaeval times the Bocage Virois would have provided ideal conditions for artisan iron-smelting and charcoal burning. The were small pockets rich in iron ore on exposed hill-sides which were surrounded by thick woodlands and forest. Clay – necessary for clamps, furnaces and temporary housing is abundant in the valleys of the Vire and its tributaries.

Charcoal burners usually lived in rudimentary woodland huts, often made of stacks and clay, and the work was potentially very dangerous since the burning process produces methane. In mediaeval times the Bocage Virois would have provided ideal conditions for artisan iron-smelting and charcoal burning. The were small pockets rich in iron ore on exposed hill-sides which were surrounded by thick woodlands and forest. Clay – necessary for clamps, furnaces and temporary housing is abundant in the valleys of the Vire and its tributaries.

However, two important questions arise:

1. How did Pont-Farcy, in the heart of the rural and agricultural 'bocage' develop this obscure speciality in high-quality, precision metal-working?

2. Why, in Lower Normandy, are all lantern clocks of this period known generically as 'Pont-Farcy' clocks – a sort of brand-name which applies to clocks whose parts may or may not have been made in Pont-Farcy and which were almost certainly often assembled elsewhere?

The answer to the first question must surely be that an artisan tradition of high quality metal working already existed in Pont-Farcy prior to the adoption of clock-making in the 17th century.

R. CHAVIGNY supports this argument, saying he knows of many examples of towns in France where men with access to iron and charcoal would, in their spare time, make plough shares, scythes, sickles, nails, locks, hunting weapons or even shot-guns. Then, one day, someone asked them to make a clock... and these clocks, he says, were each built to order. Not until later, following the examples in Germany, the Jura and southern France, did quasi-industrial practices begin to appear in places like Normandy.

Le concept d’horloge de Pont-Farcy ne semble s’appuyer sur aucun écrit, aucun document ; cette terminologie est adoptée ici du fait qu’elle a été utilisée par la plupart des personnes consultées lors de mes investigations. En fait, Pont-Farcy semble constituer le « centre de gravité » d’un terroir (fig. 7) où l’on produisit, entre le XVIIIe et le milieu du XIXe siècle, un type d’horloge qui caractérise un savoir-faire spécifiquement bas-normand. David Nicolas-Méry

The most specialised iron-working skills in France would have been needed to manufacture precision-made, durable components for clocks – skills shared only by the best armourers, locksmiths, gunsmiths, etc. The ability to smelt, refine, forge and finish ironwork to this quality surely existed before the demand for clock components. No one would have imported high-grade iron and skilled artisans into the wilds of the Bocage Virois if the skills were more conveniently available elsewhere.

Two possible answers to the second question each reinforce the answer to the first:

1. Although clocks are known to have been made in several towns in Lower Normandy, perhaps they were assembled from parts which were advertised as having been 'made in Pont-Farcy', thus implying a known reputation for quality. Quality of this degree in turn suggests that the requisite skills in smelting, refining, forging and finishing already existed.

2. That Pont-Farcy was the first town associated in the public's mind with the production of distinctive 'lantern' clocks and thus gave its name to all such clocks wherever they were made. If this were true it cannot be an accident that Pont-Farcy was a leader in precision metal-working.

CONCLUSION: Skilled artisan iron-workers were already established in Pont-Farcy prior to the arrival of clock-making in Lower Normandy (at least as early as the late 17th or early 18th centuries) and that their reputation for quality was sufficiently high that all such clocks in the region were known by the Pont-Farcy 'brand name'. The activities of these iron-workers prior to the arrival of clock-making has yet to be determined.

I

t is not known to what extent water power served the needs of artisan iron workers before the arrival of the industrial age in the 19th century.

The author is aware of research done into pre-industrial age water mills along the river Vire, many of which survive and are known to have been involved in milling grain, beating textile pulp for the paper trade, extracting vegetable oils, etc.

At Tessy-sur-Vire (above) the river Vire powered a saw mill as well as more conventional water mills, like the one at Fervaches (below). Other mills were used to beat pulp for paper-making and extract linseed oil.

In the 19th and 20th centuries, in the Vaux de Vire quarter of the town of the Vire, the river was harnessed extensively for industrial purposes and must surely have served pre-industrial artisan workshops in earlier times too.

In the area the author has identified as potentially involved in iron-working (the body of land contained by bends in the river from Campeaux to the Roches du Ham) there are many surviving mills which profited from the steady supply of fast-flowing water in steep descent. Did iron smelters and iron workers harness water power at any time from the late-Middle Ages onwards and, if so, how? When, for example, did water-wheels first drive trip-hammers or fan air into furnaces?

It would be interesting in future to seek the advice and cooperation of archaeologists in Britain such as those working on the Stanley Grange site. We hope to make contact with them soon. Below are some notes from Patrice de Rijk of Trent and Peak Archaeology who worked at Stanley Grange, Derbyshire, in Britain.

Stanley Grange is one of only a handful of medieval iron smelting sites known from excavation within Britain and is contemporary with the rapid and dynamic technological developments that characterised European iron smelting between the 11th and 14th centuries. In this period a gradual transition took place from the direct production of iron in low shaft furnaces or “bloomeries” to the indirect production iron in blast furnaces. The terms direct and indirect refer to the subsequent treatment of the produced iron: in a bloomery malleable iron is won in a solid state extraction process, in a blast furnace fluid cast iron is produced that has to be decarburized in a subsequent fining process to make it malleable. Such technological developments had a significant impact on European society and economy.

In the meantime, the most convincing proof that iron-working took place in the study area would be the discovery of slag looking something like the samples below!

- Study of any written sources regarding any activity directly or indirectly related to iron working in Basse-Normandie.

- A geological analysis of the region to identify areas most likely to have been rich in accessible iron ore (bearing in mind that some sites may already have been worked out and these may have been obscured by erosion and/or human activity).

- A ground search in likely areas for iron extraction to see whether any traces of artisan furnaces or slag heaps remain. Given the experience at Stanley Grange (see right) positive results seem unlikely, but one never knows...

- What connection if any with La Hatuyère, Pont-Farcy, which directly overlooks the iron-rich area of Pleines-Oeuvres and which itself may have pre-Norman origins...

- Continue searches for any local toponyms and tell-tale signs in the landscape. Fer-, -fer, Carbonnière, Carbonière, etc

- Learn from (and co-operate with) the work of others doing similar work in Europe.

- Robert Waterhouse: characteristics of iron bloomery / blast furnace sites [pdf]Click to see Robert Waterhouse's helpful thoughts...

The author owes a great debt to:

industrial archaeologist Robert Waterhouse

geologist John Renouf

historian Dominique Doublet

historian-archaeologist David Nicolas-Méry.

See Iron Rich Rocks at Pleines-Oeuvres

D. DOUBLET Farcy De Guilberville 1

D. DOUBLET Farcy De Guilberville 2

D. DOUBLET Seigneurs de Mesnil-Guérin 1

D. DOUBLET Seigneurs de Mesnil-Guérin 2

D. DOUBLET Seigneurs de Sédouy 1.pdf

D. DOUBLET Seigneurs de Sédouy 2.pdf

D. DOUBLET Images

© (2014) Christopher A. Long. Copyright, Syndication & All Rights Reserved Worldwide.

The text and graphical content of this and linked documents are the copyright of their author and or creator and site designer, Christopher Long, unless otherwise stated.

No publication, reproduction or exploitation of this material may be made in any form prior to clear written agreement of terms with the author or his agents.