An archaeological study

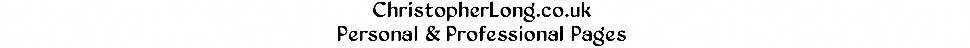

A study of a small ensemble of houses and agricultural buildings built between the C15th and C19th on five hectares of land in the Bocage Virois.

This is a rare example of a Normandy hamlet (village or hameau) which remains almost intact and remarkably untouched by the effects of C20th and C21st agricultural 'improvements'.

Village | Maison | Chaumière | Laiterie | Puits

Grange |

Porcherie & Poulailler | Étable à Vaches

Charterie & Étable |

Four à Pain | Étable à Veaux

Maison Goddard | Pressoir | Lavoir

By Christopher Long

The Village of Le Boquet

L

e Boquet is a typical rural village in the Bocage Virois in Normandy, France. A village in this sense is a group of perhaps four or five houses which once shared communal facilities such as a well (puits), a dairy (laiterie), a bread-oven (four à pain or boulangerie), a cider press (pressoir) and an open-air washing-place (lavoir), etc. At Le Boquet four 'houses' remain and only the pressoir, destroyed in the 1999 gale, has not survived.

Le Boquet may have been inhabited from at least the C15th, judging by masonry in its earliest surviving building. In October 2016 Robert Waterhouse provisionally identified stonework in the Boquet building as consistent with at least five phases on construction: C15th, C16th, earlier C17th, later C17th and C18th. The clay/cob northern extension (stable and pig sty) is clearly C19th.

appear in the C18/19th Carte de Cassini, marked as a hamlet, while several surviving elements (notably doors) in the house/granary and in the principal house at Le Boquet appear to date from the C17th and C18th. A number other buildings in the group are almost certainly C19th and date from the agricultural revolution of the mid-1800s when dairy farming overwhelmingly replaced arable farming, sheep breeding and cider production as the principal farming activities in the region.

It is hard to say where the limits of Le Boquet were from the C16th to the C18th. New roads and the effects of the commune system introduced after the 1789 French Revolution have altered the administrative landscape. The dark green area in the small image above indicates the two parts – Le Boquet and Le Bosquet – as they are today, Le Boquet lying in Pont-Farcy and Le Bosquet in Ste-Marie-Outre-L'Eau, divided by the D306.

Le Boquet appears once to have consisted of at least 10-15 hectares (25-38 acres), now lying on either side of a road (the D306). Until any original documents are found one can only work from what the surviving place-names (toponyms or lieux-dit) suggest.

The simplicity of the surviving buildings does not suggest a large estate. However, Le Boquet is one of only handful of specific places in the area mentioned by Cassini – its nearest neighbours being Beauregard, La Clémendière, La Torignière, La Sallière and Le Moulin Hy.

It is unclear where the boundary lay with La Fosse de Bas to the south, whose farmhouse was certainly built much later. It is also possible that it originally included an area of land to the north-east, near La Noette, lying between the steep 'new' section of the D306 road and the 'old' road (a now disused sunken lane or chemin creux). The reasoning behind this is that before then there would have been no natural boundary prior the construction of the 'new' road.

However this study concerns only the western half of the original area, marked in dark green in the large plan above, which includes nearly all the buildings and which now belongs to the author and his wife.

However this study concerns only the western half of the original area, marked in dark green in the large plan above, which includes nearly all the buildings and which now belongs to the author and his wife.

[Note 1. Most of the D306 road is probably ancient though the steep hill section running within an embankment from the Moulin Hy to Le Boquet was probably built in the late C18th or early C19th. Before then the road presumably followed the old and now abandoned chemin creux which still represents the boundary between the communes of Pont-Farcy and Ste-Marie-Outre-L'Eau. Communes were established after the 1789 French Revolution to replace parish administration though they sometimes re-defined boundaries. It should be noted that much of the D306 has steep embankments on each side and was probably lowered to make it easier to use. Since at least the early C19th the major part of Le Boquet has fallen within the commune of Pont-Farcy, while the smaller part lay within St Marie-Outre-L'Eau. But for the purposes of the official cadastre the two adjacent villages each continue officially to be called Le Boquet or Le Bosquet. Today both are often colloquially referred to as Le Bosquet. It seems safe to assume that Le Boquet in the C16th and C17th would have comprised the land on both sides of the D306 which itself probably incorporates parts of more ancient local lanes.]

[Note 2: In addition to the D306, a lane once passed through the middle of the village of Le Boquet – parts of which are still visible today. This lane appears to have begun at a cross-roads to the north-east of Le Boquet's 'Barn' and ran past its north-west main door, continuing past the (south-east) front door of the main Le Boquet house and running south-west through La Sallière. It may even have extended as far as Le Ménage. It certainly passed the front doors of at least five other houses built in a straight line and had branches leading off across the valley to La Sourcière (a chemin creux which still existed in 2010) and to La Bénouvière (visible in 2010 but no longer accessible). One part of the main lane can still be seen in the plan above, marked as the 'Avenue'. Another part is still in use as a road. This lane may have formed part of an ancient by-way from Pont-Farcy to St Vigor-des-Monts. From Pont-Farcy it would have crossed the Gouvette stream east of Le Moulin Hy and climbed to Le Boquet through a chemin creux (this section being still visible but blocked by municipal rubbish). At Le Boquet it would have offered routes eastwards and southwards to La Noette, La Thorinière and La Fosse. From Le Boquet it led on to La Sallière and Le Ménage before heading off, as it does today in the form of a road, to Les Monts, where it crossed the Drôme river for La Recouvière. An alternative road on the western side of the valley followed the ancient Gallo-Roman road, still known as La Pavée, running from Le Moulin Hy via Beauregard to Ste Marie-des-Monts and then on to Villedieu-les-Poêles. Much of this second route was still accessible in 2010 – though most of La Pavée in the commune of Pont-Farcy has been neglected or lost while, once again, a length of it has been blocked by municipal rubbish.]

Today the village of Le Boquet remains remarkably intact. The stone Well, set in what was once an apple orchard, stands at the centre of a group of four houses. It is not known whether the visible stonework above ground is original. The well's access point faces away from what is presumed to be the earliest building (the house/granary) and towards what is thought to be a relatively recent (and currently abandoned) house. A Bread Oven is still in situ nearby. Sadly, following severe storm damage in 1999, all that remains of a former pressoir on the southern end of the House/Granary are its foundations and some of its wooden elements. The lavoir is still visible upstream in the valley below, fed by a natural spring.

Today the village of Le Boquet remains remarkably intact. The stone Well, set in what was once an apple orchard, stands at the centre of a group of four houses. It is not known whether the visible stonework above ground is original. The well's access point faces away from what is presumed to be the earliest building (the house/granary) and towards what is thought to be a relatively recent (and currently abandoned) house. A Bread Oven is still in situ nearby. Sadly, following severe storm damage in 1999, all that remains of a former pressoir on the southern end of the House/Granary are its foundations and some of its wooden elements. The lavoir is still visible upstream in the valley below, fed by a natural spring.

Elsewhere — though not part of the 'communal' property – are other buildings built of solid clay on stone footings: a small Calf Shed, a similar sized building, opposite the principal house, designed as a Dairy and, in the extreme south-west, a very modest single-room Cottage which was inhabited until the 1950s.

Other such buildings may have disappeared. For example, an almost lost clay-on-stone Workshop atelier attached to the principal house at Le Boquet was being restored in 2010 while in the early C21st there was still clear evidence of the footings of a small building on the north-west side of the Avenue (see map above). At the time of writing the foundations of this little building lie beneath a large wild cherry tree between the Cottage and Le Boquet house.

The Bocage Virois was far from being a prosperous region until the end of the C20th. Granite was used for the coins, doorways, windows and chimneys of most surviving farmhouses from the late Middle Ages until the C19th, but nowhere was expensive granite used at Le Boquet until some C20th improvements were made to the House.

Indeed, even though the land itself is extremely rich, the preservation of Le Boquet as an unimproved C19th farm (even after the introduction of tractors in 1959) may be due to its relative poverty on the slopes of a small valley where much of the land was not plough-able. For this reason too Le Boquet retained many of the most characteristic features of the Bocage landscape, including its flora and fauna. Sadly many magnificent trees, which had survived the 1999 storm, were cut down by René Hébert before he sold the property in 2000/2001.

All the indications are that this modest village had always been at the lower end of the scale as a subsistence farm. It is not known whether Le Boquet (originally perhaps 10-15 hectares) was ever farmed as a single unit although this seems likely given the volume of the Barn.

Major changes and re-structuring are likely to have occurred following the French Revolution of 1789 and it may be that the property was divided into separately owned parcels at about this time.

[Note 3: Certainly by the mid-C20th it consisted of four separately owned units. To the west of the D306 two areas were farmed separately by the Hébert and Cordhomme families. The eastern side of the D306 was farmed by the Dedieu family and, from the 1960s, by Marcel Scelles). Three fields (about two hectares) at the north-eastern point and along the western bank of the stream) belonged to the neighbouring Gesnouin family (in the village of Le Moulin Hy) separated from the rest of their farm by the 'new' Villedieu-les-Poëlles road which sliced through their land. The remains of a separatelavoir at an artificial bend in the stream within the Gesnouin land suggests that it had been separately owned for some time. Additionally a very small area, beside the main road and surrounded by the Gesnouin land, had been acquired at some stage by a small house across the road. On the other hand, two parcels of land lying in the neighbouring village of La Sourcière (west of Le Boquet), including the valley bottom and its stream, were incorporated into the Le Boquet farm during the C20th.]

Significantly, a small rectangular piece of land lying astride the same stream had 'always' belonged to Le Boquet. The explanation for this is clearly that the natural spring there served as Le Boquet's communal lavoir. Owing to the steep drop to the valley, this would have been the only spot in the vicinity where there was relatively easy access from Le Boquet for anyone carrying a quantity of washing. In 2010 vertical slabs of stone which once formed the edge of the lavoir basin were still clearly visible.

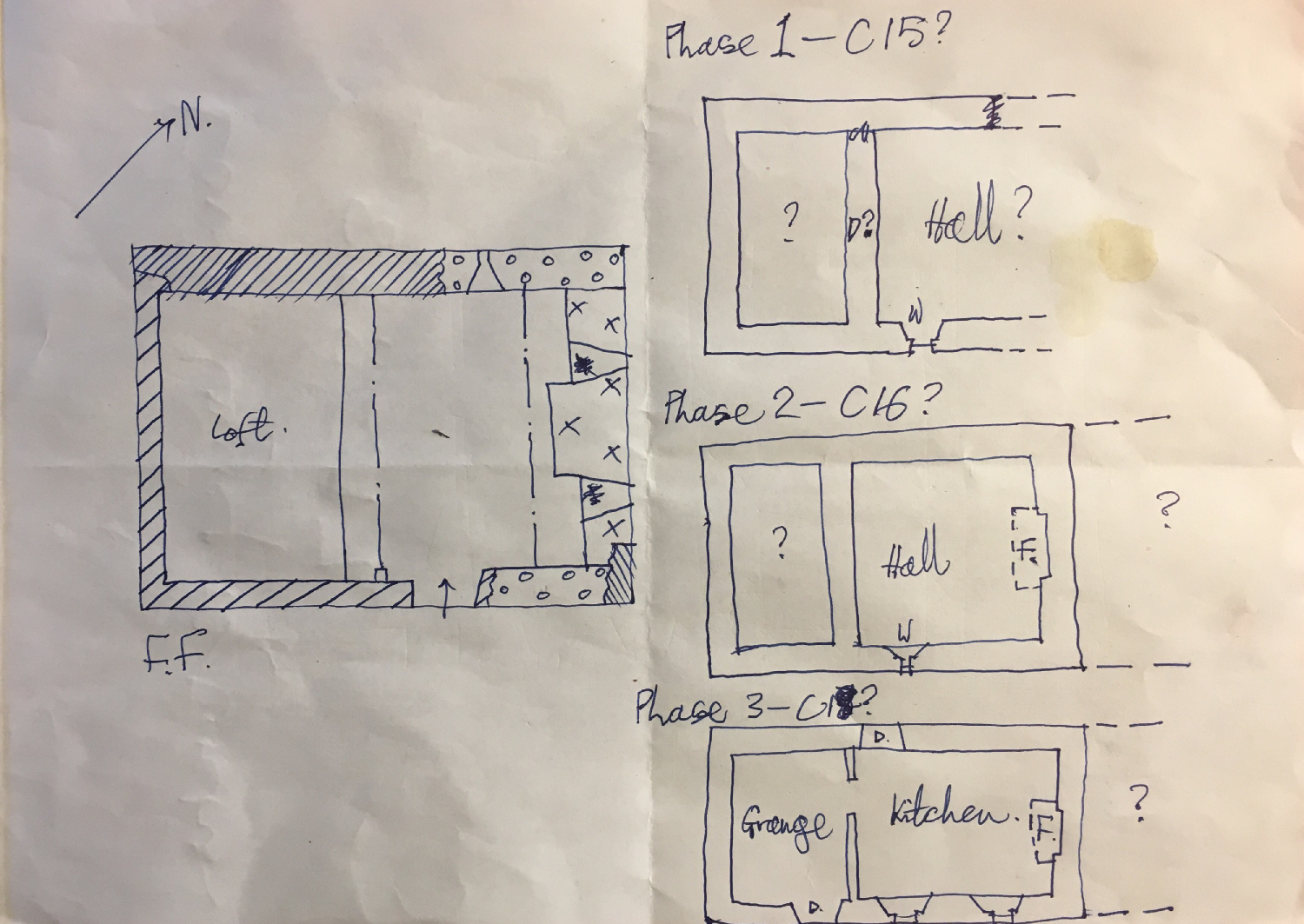

Two of Le Boquet's buildings are of particular interest: the Barn (which in this report will be described as Le Boquet) and the nearby principal House.

The Barn (or grange)... an enigma...

perhaps dating from the mid C16th...

T

he building we call the 'Barn' is a puzzle. Looked at from the west it appears to be nothing more than an early, well-proportioned and well-built farm building – perhaps a C16th barn of some sort.

Seen from outside

Looked at from the east it is clearly a habitation with two primitive windows set into a partially rebuilt east wall which also contains an exit, set low, from an internal sink (un évier).

Looked at from the north, the gable end wall was clearly built to contain the surviving chimney and two light embrasures set high on either side of the conduit.

By local standards of the C16th-19th, this is a large, well-proportioned building. Its walls cover a footprint of about 81 sq. metres and consist of at least four separate styles of masonry under a thatched roof.

Today the lateral walls support three frames (one set at an angle) and are almost 100 cms thick at ground level.

However, puzzlingly, on the eastern side no attempt has been made to key the lateral wall into the chimneyed gable end wall.

On the western side, a half-hearted and 'bodged' attempt has been made to key a few stones of the lateral wall into the chimneyed gable end wall. These 'joints' have now nearly all fractured.

Click on the image (right) to see a larger version which may enlarge further if clicked again.

Seen from inside

The northern half consists of an almost untouched living room (known locally as the maison) with an intact chimney breast, set over its original hearth, and built into a gable wall (un pignon) of almost mediaeval form, incorporating two light embrasures set higher than the roof-plates (les sablières) as though intended to provide light to a room that was once open to the roof. However, this gable wall is not keyed into either of the lateral walls.

The southern half, accessible today via a small internal doorway set into a timber partition (and accessible from outside via its own tall, external doorway) consists of a large, raised 'grange' with a beaten-earth floor (terre battue) and a high ceiling which, well into the C20th, was still being used by men armed with flails to separate the grain from chaff at harvest time. However, the wall which retains this raised area – and on which the partition sits – is not keyed into either of the lateral walls and appears to be of more recent construction.

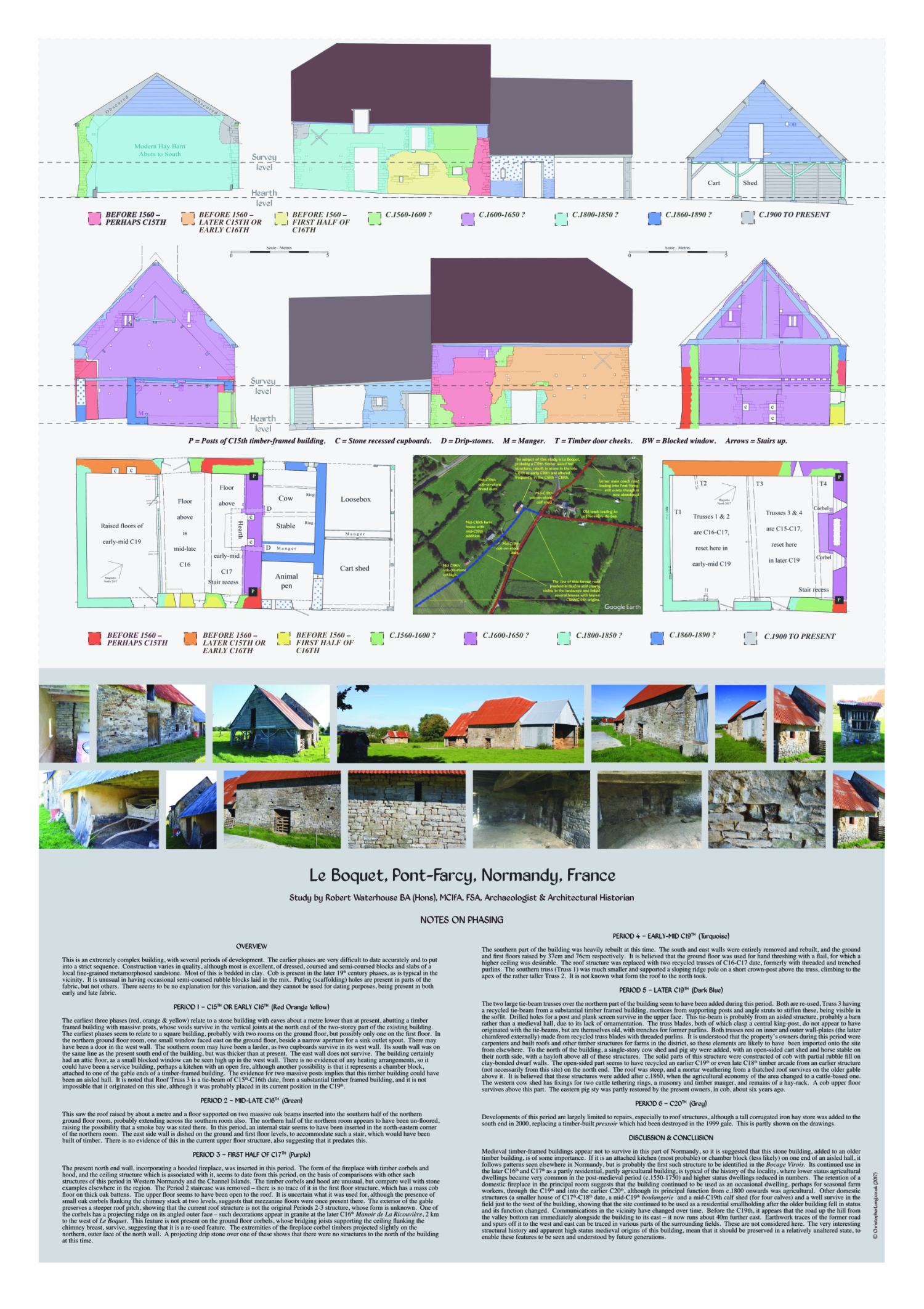

In order to 'understand' this building we need to know whether the gable wall was built before or after the western lateral wall. If the gable was built before the lateral wall, the likelihood is that a habitation was intended but that it was abandoned before completion and that the gable was simply incorporated into a subsequent farm building which was, in turn, later transformed back into a habitation (see arguments below).

If the gable wall, with its chimney and fireplace, was built after the construction of the western lateral wall it would seem that the gable end of a relatively early farm building was demolished, rebuilt and that the eastern wall was then (or more likely later) converted in one or more stages to provide light for the interior.

Although it may have been built in the C16th, this building could well have been abandoned for some time as a consequence of the devastation and rural depopulation caused by the plague years of the C17th. In any case, it was certainly converted for use as a habitation in perhaps the late 18th or early C19th. At this stage the open ground floor space was divided in two unequal halves by a timber partition.

However, in order to provide some light into the room, one or two windows were at this stage introduced (there were certainly two by the C20th). To achieve this it appears that the external staircase (built into the thickness of the lateral wall in the south-east corner of the building) was removed and about half of the south-east facade rebuilt. Fortunately this rebuilding, which also created more space in the living-room, was badly done using a different stone and bodged in-filling using clay. Thus the position of the external stairway can still be discerned from the old stone coins visible in the poulaillère and in the hay-loft above.

A maison (single habitable living-room) was created in the larger part with the addition of a fire-place and chimney, while windows openings were made which in turn required the removal of the outside stairway. This conversion also involved a substantial oak-timbered ceiling and a oak-framed chimney-breast, although the floor probably remained beaten-earth. The main door into this room remained the former agricultural doorway which, understandably, was reduced in width.

Pictured right, above and below, the interior of the former barn showing the partion on the extreme right and windows providing light to the room that was created when the barn was converted into a habitation. To create these windows an external staircase was presumably removed and the wall rebuilt in the late C18th or early C19th.

In the other, smaller half of the ground floor, accessible through a small door in the timber partition, was a typical raised grange (barn). This would have served as the working area for storing tools and materials, while its raised ceiling allowing for the hand-threshing of grain in summer. The grange now needed its own tall external door to make the area accessible it from outside.

Pictured right, a new internal wall was built against the original northern gable end wall of the former barn to form a fireplace and chimney. The stonework of this wall is not keyed into the older walls, indicating that this was a later construction dating from the conversion of the barn into a habitation.

The first-floor level presumably remained a granary until the arrival of dairy farming when the majority of the space would have been given over to the storage of hay and straw for cows during the winter. Grain however would have continued to be grown in smaller quantities for bread-making, feeding chickens, as an additional cash crop in hard times and as a food supplement for cattle.

It seems very likely that this building ceased to be a habitation around the time of the mid-C19th agricultural revolution since there is no evidence of it having been adapted for dairy use. It is likely that its former inhabitants simply moved to the house (abandoned since well before the end of the C20th) about 50 metres to the west which may even have been built at this time.

Pictured right: the vertical break in the stonework, visible in the northern gable end wall both at ground-floor and first-floor levels, indicates that there was almost certainly an external staircase which once provided access to the first floor of the barn – a staircase that sat within the thickness of the south-eastern lateral wall.

C19th additions: a chicken shed (poulailler), cow shed (étable à vache),

stable (étable à cheval), cart shed (charterie), calf shed (étable à veau)

and bread oven (four à pain or boulangerie).

The pig byre (or porcherie)

At some time, in the C19th, a porcherie (pig byre) and an étable (cow shed) were built on to the north-east end of the Barn. The pig byre also seems to have served as a chicken shed (see surviving and restored pop holes). Their walls were built of solid clay on stone footings about one metre high. Later still, within a timber arcade, an open-sided charterie (cart shed) part of which was adapted to form another stable, probably for a horse.

At some time, in the C19th, a porcherie (pig byre) and an étable (cow shed) were built on to the north-east end of the Barn. The pig byre also seems to have served as a chicken shed (see surviving and restored pop holes). Their walls were built of solid clay on stone footings about one metre high. Later still, within a timber arcade, an open-sided charterie (cart shed) part of which was adapted to form another stable, probably for a horse.

Pictured right (above), the northern end of the C19th addition to the barn. To the left, the open-sided area was used as a cart shed or 'charterie'. The corresponding area to the right was presumably a horse stable. The arrival of horses on poorer subsistance farms in Normandy, required for working land and pulling carts, dates from the C19th. During the mid-C19th horses replaced cows (or oxen) as the motive power on farms. Simultaneously, specialised breeds of cow such the 'vache normande' were developed and kept for their value as producers of dairy products and beef. This revolution in agricultural practice required new buildings (often constructed of stone and clay) for their accommodation, feeding and milking during the winter. Since cows need to produce a calf each year in order to produce milk, further buildings were necessary for the housing of the calves. A typical farm in Normandy in the C19th and early C20th was thus adapted to house four cows during the winter, as well as housing for at least four calves – hence the construction of a Calf Shed as shown in the picture below.

The Calf Shed (or Étable à Veaux)

Not far away a Calf Shed was built in the same fashion (solid clay on one metre high stone footings). It was originally divided into two halves by a timber partition (the top and and bottom of which are still visible), each with its own doorway. It seems to have been intended for stabling four calves. In 2010 the wooden attachment points for tethering calves in four corners of this small building were still visible or actually in place. From the similarity of the clay and stonework, it would be reasonable to suppose that the Bread Oven (four à pain) was built at the same time.

Not far away a Calf Shed was built in the same fashion (solid clay on one metre high stone footings). It was originally divided into two halves by a timber partition (the top and and bottom of which are still visible), each with its own doorway. It seems to have been intended for stabling four calves. In 2010 the wooden attachment points for tethering calves in four corners of this small building were still visible or actually in place. From the similarity of the clay and stonework, it would be reasonable to suppose that the Bread Oven (four à pain) was built at the same time.

The Well (or Puits)

The Well almost certainly dates from the first settlement of Le Boquet. Being the only well on the property and very deep (at 10-11 metres – 35 feet – to water level) no one could have lived on the property without this reliable supply of good quality water. Although its masonry may have been repaired from time to time through the centuries, it is one of the few in the area still equipped with an early timber lifting mechanism, complete with hand-brake. It was almost certainly thatched until the mid C20th and may once even have been covered by the conical stone roof typical of the local tradition.

By November 2016, the rotting timber and rusted corrugated iron roof was in a dangerous condition and needed to be replaced. When dismantling the well-head and the top layer of stonework which held it in position, we found a mason's token: a French 1 franc coin dated 1942 bearing the 'Travail Famille Patrie' slogan of the war-time Vichy state. This clearly shows that the roof structure (as shown right) was erected in 1942.

The chain and roller were still in good enough condition to be re-used in a replacement well-head. A steel safety grill with a lockable trap was installed by Didier Hury prior to reconstruction.

By the mid-C20th...

The Barn and its associated additions were by now being used as general purpose farm buildings by the inhabitants of the house 50 metres to the west. The owner was a carpenter and joiner (René Cordhomme) who continued to keep three or four cows, milked by his wife Marie in the fields around.

The former Living Room (maison) in the Barn was by now used only for storing bottled cider and preserved fruit and vegetables. A rudimentary electricity supply had been added (since 1936) to provide some lighting and to feed a refrigerator. The space was dominated, however, by three large cider barrels (1,400 litres each). A pipe led underground from the barrels to the now-disused Bread Oven (four à pain), 50 metres away, where the Cordhomme couple distilled the cider to make calvados. The barrels, pipe and the 'still' remained in situ in 2010.

The former Living Room (maison) in the Barn was by now used only for storing bottled cider and preserved fruit and vegetables. A rudimentary electricity supply had been added (since 1936) to provide some lighting and to feed a refrigerator. The space was dominated, however, by three large cider barrels (1,400 litres each). A pipe led underground from the barrels to the now-disused Bread Oven (four à pain), 50 metres away, where the Cordhomme couple distilled the cider to make calvados. The barrels, pipe and the 'still' remained in situ in 2010.

The domed end of the Bread Oven (this would again have been of clay on stone footings) had disappeared by 2010 (probably after 1945) to make way for an open-air lavatory. However, it remained otherwise substantially complete with the oven doorway simply blocked up. Restoration of the whole structure began in Spring 2011, starting with the rebuilding of the domed oven itself.

The Calf Shed (about 5 square metres) may still have been used for up to four calves (within the unit once divided by a partition), though elderly neighbours in the early C21st remembered that a journalier (occasional labourer) was sometimes housed there "with his wife and children"... presumably just before or soon after WWll. This seems very plausible since a rudimentary fireplace and chimney, made of modern bricks and cement was installled (still in place there in 2010) and human occupation would also explain the removal of the partition.

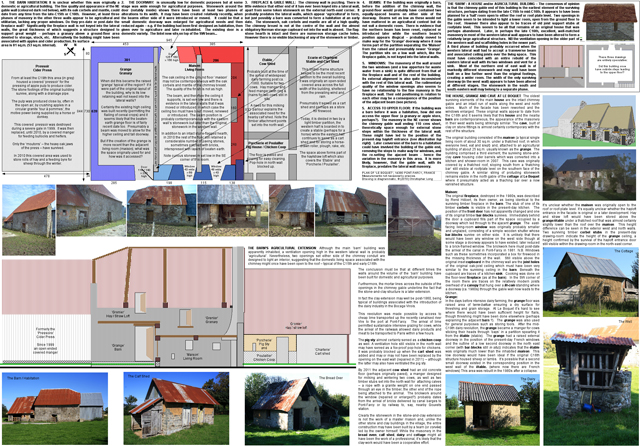

The House at Le Boquet (or Le Bosquet)

NOTES

On 29-06-2010 The historian and archaeologist Julien Deshayes (Pays d'art et d'histoire du Clos du Cotentin) commented that, in his own Cotentin region, granary barns occupy the ground-floor, needing no stairway access. On the other hand, he says, cider presses (pressoirs) in north Manche have external stairways to an apple store on the first floor. Until more studies can be made and any remaining traces of a pressoir can be found within the principal Le Boquet building, this study holds to the theory of a grain barn as the most likely purpose of the building at Le Boquet, at least until it became a habitation. Julien supplied a fascinating C17th drawing of the manor and farm courtyard layout at Réville (Manche) which supports his point.

On 29-06-2010 The historian and archaeologist Julien Deshayes (Pays d'art et d'histoire du Clos du Cotentin) commented that, in his own Cotentin region, granary barns occupy the ground-floor, needing no stairway access. On the other hand, he says, cider presses (pressoirs) in north Manche have external stairways to an apple store on the first floor. Until more studies can be made and any remaining traces of a pressoir can be found within the principal Le Boquet building, this study holds to the theory of a grain barn as the most likely purpose of the building at Le Boquet, at least until it became a habitation. Julien supplied a fascinating C17th drawing of the manor and farm courtyard layout at Réville (Manche) which supports his point.

External staircases can also be found in habitations. In the Bocage Virois, as in Britain and elsewhere in Europe, the house of a feudal lord (a manor house or seigneurie) was characterised by the presence of an upper private chamber (chambre haute) accessible by a stairway. In larger manors this staircase is internal and in some cases leads up to a first-floor gallery along the lateral wall of the 'hall', thus providing access to the lord's private chamber(s) beyond the end wall(s) of the hall.

In the author's view, the famous 'arras' referred to by Shakespeare was not a tapestry hanging against a vertical side wall but rather a tapestry or woven 'partition' (which the English would naturally have associated with the great weaving city of Arras in northern France, to which they exported wool and which was once their colonial possession) which would have hung between the gallery and the hall floor, thus separating the 'lord's' private space in his hall from a communicating service corridor under the gallery and 'behind the arras'. From behind this 'tapestry or 'arras' the servants might indeed have overheard their lord or king discussing private business. In this respect, Court Lodge (Westerham, Kent, England) provides a perfect example of a C15th or C16th 'seigneurial' layout with a galleried hall that has its exact parallel in Normandy at the same period.

In the author's view, the famous 'arras' referred to by Shakespeare was not a tapestry hanging against a vertical side wall but rather a tapestry or woven 'partition' (which the English would naturally have associated with the great weaving city of Arras in northern France, to which they exported wool and which was once their colonial possession) which would have hung between the gallery and the hall floor, thus separating the 'lord's' private space in his hall from a communicating service corridor under the gallery and 'behind the arras'. From behind this 'tapestry or 'arras' the servants might indeed have overheard their lord or king discussing private business. In this respect, Court Lodge (Westerham, Kent, England) provides a perfect example of a C15th or C16th 'seigneurial' layout with a galleried hall that has its exact parallel in Normandy at the same period.

External staircases, at least in the Bocage Virois, appear in small manor houses (sometimes very small), presumably because there would not have been sufficient space within, given the small volume of the 'hall'. The lord's chamber usually sat over a secure storage room containing the family's most valuable assets, stores and possessions. This ensemble is sometimes known as the principle of the 'hall and chamber block'.

The historian and archaeologist David Nicolas-Méry (Ville d'Avranches) has demonstrated a third application for an external staircase in southern and central Manche (Normandy): a staircase leading to a comfortable chamber above a bake house (four à pain or boulangerie). It is believed that this provided an independent and permanently warm room for an ambulant feudal lord while visiting his estates. It must be stressed, however, that there is no remaining evidence at Le Boquet of any building of manorial status. Hence the external stairway in its principal building must be regarded as having met an agricultural need.

The House at Le Bosquet

- A 5 metre ladder once hung along the west wall of Le Bosquet supported by a pair of timber stubs, one of which was still in place in 2011.

- A hole in the old (lower) masonry north wall, about one metre above the ground and since roughly blocked in by René Hébert, once gave chickens access to the cow shed inside.

- A ventilation hole in the west wall near the entrance into the cow shed has been been blocked but its outline remains visible.

- The interior of the north wall of the cow shed, rendered prior to 2001 by René Hébert, was badly eroded by cows which had rubbed their bottoms against it for many generations.

- Within the cow shed, near the centre of the north wall and about a metre above ground level, was a typical stable 'niche' for a lantern and/or for storage. It was adapted in about 2004 to pass a chimney pipe from a Godin stove through the wall to a vertical stainless steel chimney outside.

- Among the 'improvements' made by René Hébert was the destruction of the grange and of its four timber bays. Cows standing in the cow shed, passed their heads through the bays to feed on hay dropped onto the floor of the raised grange from a hayloft above.

- Originally the floor of the grange, invariably with a beaten earth floor, would have been at or above the level of the adjacent main living-room (maison) while the floor of the cow shed would have been about 50 cms below this.

- There were two ways accessing the grange: either from within the house via a small door immediately behind the front door into the maison (by 2001 this had long converted into a cupboard), or alternatively via a raised external doorway adjacent to the same main doorway (transformed and widened before 2001 to create a French window).

- The name grange derives form the centuries during which grain was the principal farm product in this area and teams of men, armed with flails, beat the freshly cut wheat, barley, etc., to separate the grain from the straw. With the arrival of a widespread dairy industry in nearly every local farm in the mid-C19th, the grange served both as a granary in summer and as a manger for cows in winter (as well as a place for storing valuable hand tools and equipment).

- The cow shed has had two entrances for allowing cows in and out as well as for removing manure and slurry. At Le Bosquet a low doorway at the northern end of the east facade is still visible although it was blocked up a long time ago. Inset timbers remain visible on either side of the doorway to allow for 'barring' of the doorway. According to René Hébert in 2011, an identical doorway existed on the opposite (western) wall which he enlarged to form a French window. Given the slope of the land, it is likely that the former doorway was used for evacuating manure and slurry.

- Prior to 2001 René Hébert created a single living room from the former grange and étable, at the low level of the former étable but water-proofed it and entirely lined it with white tiles. In 2011, C & S Long raised the level of the floor of this room by about 25 cms with timber joists and a timber floor.

- In the living room, on the south wall, can still be seen two of the timber corbels that once supported the ceiling of the grange and étable and the hayloft above. At the same level as these two corbels, on the east wall, can be seen the bottom of the original external doorway into the hayloft. This recess survived the rebuilding of the exterior masonry on the eastern facade of the former grange and étable. This rebuilding occurred when the single story building was raised to create living space above. In the last decade of the C20th René Hébert himself replaced a clay (argile) upper wall on the north and west sides with badly laid stone that he had transported from the post-WWll salle des fête from Vaudry. Still visible in the fine quality external western wall stone-work (C16th?) of the grange & étable is a blocked up ventilation hole and one of a pair of timber 'pegs' set high in the same wall on which a long ladder was once hung. Meanwhile a niche for a lantern in the north wall within the étable was used in 2002 to provide an exit through the wall for the flue of a wood-burning stove.

Le Boquet Study Slide Show (2011)

Pont-Farcy – Some notes on its history

Traditional methods used in the building & restoration of rural structures in the Bocage Virois (2011)

Patois & The Norman Bocage Today First steps in understanding patois and Norman habits (2002)

Normandy: The Search For Sidney Bates, VC A story of outstanding courage in the Battle of Normandy (2003)

Les Frères Duval et Leurs Aviateurs Americains American airmen hidden in Pont-Farcy in WWll (2003)

Tales of The Magic Wardrobe Explaining histry through strip cartoons (2007)

Mont Saint Michel in Normandy and St Michael's Mount in Cornwall Linking two St Michael's Mounts (2007)

Tonsures, Tin, Bronze and Bells A study of Norman links to the Cornish tin trade (2009)

St Michel, l'Étain et l'Âge des Cloches Talk given at the Archives Départementales, St Lô (2009)

L'Horlogerie Vernaculaire Bas-Normande par David Nicolas-Méry with references to Pont-Farcy (2012)

© (2010) Christopher A. Long. Copyright, Syndication & All Rights Reserved Worldwide.

The text and graphical content of this and linked documents are the copyright of their author and or creator and site designer, Christopher Long, unless otherwise stated. No publication, reproduction or exploitation of this material may be made in any form prior to clear written agreement of terms with the author or his agents.