Origins Of The Kosovo War

A Personal View – 22-08-1999

In the Balkans they say three people discussing politics represent at least four political parties. Similarly, few people in the Balkans agree on why any of its innumerable wars occurred, what happened or even who won them. This is an personal, outsider's view of what led to the tragic conflict in Kosovo which had its origins in 1987-89 and came to fruition in 1998-99.

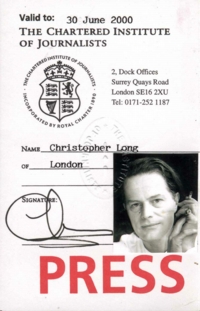

By Christopher Long

See other Balkan Affairs items.

In 1987 the newly elected president of the Republic of Yugoslavia, Slobodan Milosevic, came to power with an uncompromisingly nationalist agenda. He announced that he intended to revoke the semi-autonomous status of the province of Kosovo. In effect this was the first implementation of the 'Greater Serbia' policy, often described as: 'Where there are Serbs, there is Serbia'.

In 1987 the newly elected president of the Republic of Yugoslavia, Slobodan Milosevic, came to power with an uncompromisingly nationalist agenda. He announced that he intended to revoke the semi-autonomous status of the province of Kosovo. In effect this was the first implementation of the 'Greater Serbia' policy, often described as: 'Where there are Serbs, there is Serbia'.

Serbs existed in varying proportions in each of Yugoslavia's six states – Slovenia, Croatia, Bosnia-Hercegovina, Monte Negro, Serbia and Macedonia – as well as in its two semi-autonomous provinces of Vojvodina (predominantly Hungarian) and Kosovo (predominantly Muslims who spoke Albanian).

In Spring 1989 a peaceful protest demonstration in Kosovo's capital, Pristina, was met by brutal police baton charges that left blood-soaked doctors, students and academics in their wake. Phone, TV and radio links with the outside world were cut and the mobilisation of tanks – with jets screaming overhead – was vaguely reminiscent of Hungary in 1956 and Czechoslovakia in 1968. President Milosevic had laid down a marker for his conduct in 'Yugoslavia' during the next ten years. The outside world seemed not to have noticed.

Simultaneously, propaganda encouraged the Serb population to believe that the Serbian nation's soul lay in Kosovo and that a small C13th battlefield at Kosovo Polje, near Pristina's airport, had quasi-religious significance. In this battle, incidentally, 'Serbia' was comprehensively defeated by the Turks and Serbs fought on both sides.

Simultaneously, propaganda encouraged the Serb population to believe that the Serbian nation's soul lay in Kosovo and that a small C13th battlefield at Kosovo Polje, near Pristina's airport, had quasi-religious significance. In this battle, incidentally, 'Serbia' was comprehensively defeated by the Turks and Serbs fought on both sides.

Throughout the 1990s, state-controlled Yugoslav media were largely successful in convincing more gullible Serbs that the ethnically-mixed but predominantly 'Illyrian' Albanians were somehow latter-day Turks. Meanwhile, Serbia embarked on a series of disastrous wars with its neighbours: in Slovenia (1991), Croatia (1991-92) and Bosnia-Hercegovina (1992-95) – in each of which it dismally failed to achieve its objectives.

After 1995, Milosevic and the Serb-dominated rump of former Yugoslavia (incorporating Monte Negro) then pursued a policy of increasing political and cultural repression against Kosovo's ethnic Albanians who, along with gypsies and other minorities, constituted more than ninety per cent of its population. Albanian-language schools and universities were already closed but now a programme of Serb colonialism was introduced.

By 1996-97 Serbia was beginning to recognise that its doomed nationalist and racist doctrines had resulted in an almost total loss of power and influence throughout the former Yugoslav Republic. Reviled by the international community for its state-sponsored genocide and 'ethnic cleansing' in Bosnia, Serbia was also economically bankrupt, suffering the consequences of six years of sanctions and swamped by ethnic Serbs from Croatia and Bosnia-Hercegovina who were themselves now refugees.

By Spring 1998, most Serbs preferred not to blame Belgrade – let alone their own folly – for Serbia's catastrophic predicament, reacting instead, in frustrated rage, with more vehement support for Milosevic's increasingly nationalistic rhetoric. Milosevic's hold on power at this stage was helped by the fact that he faced no realistic opposition. He stood alone between the interminable bickering among flaccid 'democratic' opposition parties on one side and the scarcely credible fascist pronouncements of extreme nationalists such as Vojslav Sesjl on the other.

Kosovo in 1989-99 was a small, impoverished province in the rump state of Yugoslavia, situated at the southernmost tip of Serbia. Bordered by Macedonia (F.Y.R.O.M.) to the south, Albania to the west and Monte Negro (marked with a dotted line) to the north-west, its principal feature is its large central plain almost entirely surrounded by mountain ranges. In 1998/99 this landscape and the Drenica valley did not favour the lightly-armed guerrilla fighters of the KLA who were fairly swiftly driven back to a few principal strongholds up against the Albanian border. The simple road system was easily controlled by Serb transport and troops who then adopted techniques learned in similar terrain in Bosnia. These consisted of isolating towns and villages, bombarding them with artillery and then entering the remains, largely unopposed, to terrorise the local population into flight. The mere prospect of the systematic executions, torture and rape were usually enough to drive women and children into the hills while the looting and destruction of houses and farms were intended to ensure the refugees would not return.

Kosovo in 1989-99 was a small, impoverished province in the rump state of Yugoslavia, situated at the southernmost tip of Serbia. Bordered by Macedonia (F.Y.R.O.M.) to the south, Albania to the west and Monte Negro (marked with a dotted line) to the north-west, its principal feature is its large central plain almost entirely surrounded by mountain ranges. In 1998/99 this landscape and the Drenica valley did not favour the lightly-armed guerrilla fighters of the KLA who were fairly swiftly driven back to a few principal strongholds up against the Albanian border. The simple road system was easily controlled by Serb transport and troops who then adopted techniques learned in similar terrain in Bosnia. These consisted of isolating towns and villages, bombarding them with artillery and then entering the remains, largely unopposed, to terrorise the local population into flight. The mere prospect of the systematic executions, torture and rape were usually enough to drive women and children into the hills while the looting and destruction of houses and farms were intended to ensure the refugees would not return.

Milosevic, meanwhile was facing indictment for war crimes at the International Criminal Tribunal (Yugoslavia) in The Hague and well aware that his political and personal survival depended upon maintaining nationalist fervour at home while remaining an 'indispensable' key-player on the world stage.

Consequently he saw conflict in Kosovo (an internal province within Yugoslavia) as the perfect vehicle for gaining time – 'popular' at home and apparently beyond the legal powers of the West to intervene. To achieve this conflict he used the same strategy he had applied in Krajina, Eastern Slavonia and much of Bosnia in 1991-1995: rallying support at home for 'victimised' Serbs elsewhere.

Serbia was easily persuaded that fellow Serbs and their Orthodox monasteries in Kosovo were the innocent victims of 'terrorist separatists'. The so-called terrorists were in fact small and largely disorganised bands of peasant farmers – later known as the Kosovo Liberation Army (KLA) – who provided local defence against aggression from Serb 'police' units.

As the summer of 1998 progressed, Milosevic's machinations began to pay off. Provoked by increasing 'police' assaults on civilians and the murders of community leaders, the rural-based KLA grew in numbers and organisational ability, attracting financial, political and logistical support from ex-patriate Kosovars abroad. They were also almost certainly infiltrated by Serbian agents-provocateurs who encouraged the KLA to adopt a more aggressive approach that would in turn further justify intervention from Belgrade.

Under growing provocation the KLA also developed uncompromising political aspirations, playing into Milosevic's hand by calling for unconditional independence from Yugoslavia – to the point that it could indeed now be identified as an 'enemy' of Serbia, justifying the introduction of troops to preserve Yugoslavia's internal security.

The second part of Milosevic's plan also began to deliver: a rift had developed between the KLA and the 'recognised' Kosovar leader in Pristina, Ibrahim Rugova, who had always favoured a peaceful, negotiated settlement with Milosevic and Belgrade.

Less encouragingly from Belgrade's point of view, Serbia was now politically isolated. Its 'Yugoslav' partner, Monte Negro, showed increasing signs of distancing itself from Serb political and military ambitions, while its former ally Macedonia had been bribed by Western powers to play host to Nato forces hovering in the wings. Its third friend, Greece, was shackled by its membership of both Nato and the EU.

For about nine months Belgrade unleashed its well-organised military campaign of terror aimed at destroying the Kosovars' means of survival and either exterminating them or driving them out of Kosovo altogether. During the summer of 1998 the KLA was forced back to remote strongholds far from Pristina and thousands of unprotected civilians driven into the mountains and across the border into Albania.

For a year the West followed the same doomed policy that it had applied in Bosnia: it hoped to negotiate some sort of peace with proven liars and indicted war criminals whose political and personal survival depended on their continued use of military repression and violence. As in Bosnia, the Western powers refused to arm the local 'self-defence' forces who responded by becoming ever less amenable to compromise.

By late Spring 1999 huge numbers of 'Albanian' Kosovars had been exterminated and the vast majority of the population driven out of Kosovo into neighbouring Macedonia, Albania or further abroad, either temporarily or permanently. This became the largest forced migration of a population in Europe since World War ll.

Too late, Nato finally launched a sustained air bombardment on Serb military and strategic 'assets' which paved the way for the entry of Nato ground forces, KFOR, with the task of stabilising the region and supervising the safe return of Kosovar refugees.

Again failing to learn from previous Balkan experience, Western governments were astonished to find that, in turn, the returning Kosovar refugees promptly set about exacting murderous revenge on the now very vulnerable and much smaller Serb community still living in Kosovo. An age-old cycle of Balkan violence was repeating itself, just as it had in Croatia and Bosnia a few years earlier.

Not until large street demonstrations took place in Belgrade in August 1999 did the Serb population finally show the first signs of serious opposition to twelve years of adventure under the Milosevic régime.

Eight years earlier, in 1991, almost everyone in former Yugoslavia could recite the old cliché: "The war began in Kosovo and will end in Kosovo". Every one of Europe's specialist government advisers must have heard it too. No one listened.

The author was, by chance, a witness to the events in Kosovo in 1989. From 1991-1995 he was a reporter of the wars in Slovenia, Croatia and Bosnia-Hercegovina. In 1999 he was reporting events in Kosovo again from the Macedonian border.

© Christopher Long (1999). Copyright, Syndication & All Rights Reserved Worldwide.

The text and graphical content of this and linked documents are the copyright of their author and or creator and site designer, Christopher Long, unless otherwise stated. No publication, reproduction or exploitation of this material may be made in any form prior to clear written agreement of terms with the author or his agents.