Press Cards: Who Needs Them?

With specific reference to secondary accreditation.

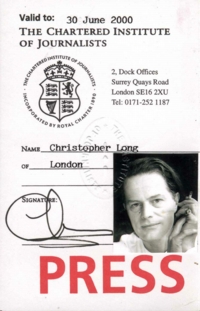

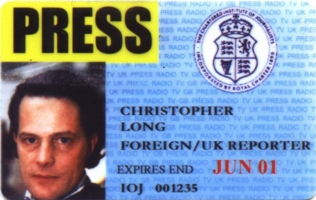

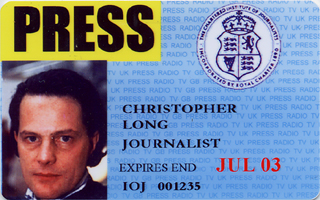

By Christopher Long 10-08-1999

One of the more vexed questions in journalism concerns the use and abuse of press cards. In whose interests are they needed? Who has the authority to issue them, to whom and on what terms? Governments, armies, police forces and countless non-governmental bodies tell us that we need the 'authority' of their own cards before they'll co-operate with us as professional, bona fide journalists. But how do they know that that's what we are? Usually by demanding to see a card issued by another authority or a letter of introduction from a news organisation of which they may never have heard!

One card only...

E

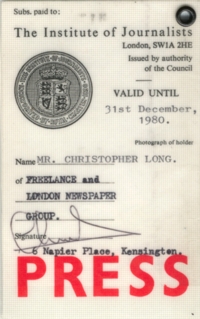

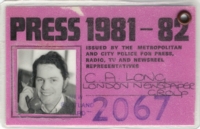

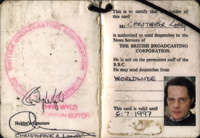

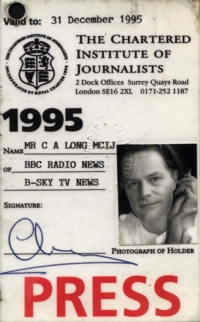

ssentially I've only ever needed one card, issued by the internationally recognised, independent professional body – the CIoJ – of which I'm a member. Among other things it asserts quite simply that I'm a British journalist who should be accorded recognition, access and assistance in conducting my work.

This is all that any journalist should need – anywhere and under any circumstances.

This is all that any journalist should need – anywhere and under any circumstances.

We are not helping ourselves or our profession when we agree to carry spurious cards issued by self-important authorities which have neither the ability nor the right to decide whether we are genuine, competent and professional.

Doctors, lawyers and teachers are not required to prove their original qualifications by carrying around packs of cards issued randomly by organisations which lack the competence to judge their credentials. Journalists are no different.

Paranoia & chaining the beast...

It's important to understand the thinking behind the issuing of 'secondary' press cards and accreditation. Fundamentally this is nearly always a sign that the organisation concerned fears or distrusts the presence of journalists. While they may not be able to deny us access, issuing cards and permission gives them the illusion that they have authority and are in control.

It's important to understand the thinking behind the issuing of 'secondary' press cards and accreditation. Fundamentally this is nearly always a sign that the organisation concerned fears or distrusts the presence of journalists. While they may not be able to deny us access, issuing cards and permission gives them the illusion that they have authority and are in control.

The stated justification for the issuing of secondary cards is usually on the grounds of 'security', weeding out 'impostors' or even in order to 'serve us better', but the fact that they issue them at all should alert us to the fact that they are troubled by our presence – the reasons for which are often in themselves worth investigating.

The 1992 London Conference press card is an example of 'secondary accreditation'. The card could only be issued to those who were already professionally accredited. This served no purpose other than to make life easier for security personnel and to give the issuers the illusion that they had some sort of 'control' over the unreliable forces of 'the media'!

As all journalists know, most governments, authorities and commercial organisations – e.g. the United Nations and Nato, see below – now devote colossal sums of money, personnel and resources to their attempts to influence or control the way the media treats them.

The effect of this largely American-inspired development is that vaguely worried organisations quickly become paranoid as armies of media consultants advise them on how best to accent the positive and limit the potential for damage. The media are soon perceived as a liability, even a cold-war enemy. Before long the organisations' executives can even be persuaded that they are competent to decide who is, or is not, an 'approved' journalist.

Sadly for these governments, authorities and commercial organisations, few are ever told that the best way to antagonise and alienate journalists and the media is to attempt to manage them – or that querying their professional status and freedom can alone almost guarantee negative reporting. Needless to say, however, such an outcome suits the media consultants who can then offer more of their expensive services in attempts to rectify the situation.

Two important issues arise from all this:

On what basis and what authority does an organisation

- decide whether to accredit us?

- deny access and co-operation if we are professionally and internationally accredited but not carrying their particular brand?

Friend or foe...

Unfortunately for us there's a world-wide, unwritten rule that such organisations select only the most blinkered and inflexible men and women to stand in their doorways or at lonely check-points demanding to see our 'passes'. They've usually been instructed to deny access or co-operation to anyone who cannot produce the card they've laboriously learnt to recognise.

Presumably they work on the assumption a 'real' journalist would be deterred from working because he didn't have the magic card and that an 'impostor' wouldn't be clever enough to fake or obtain one fraudulently – and all this pre-supposes that the person who issued them in the first place could unerringly tell the difference between the two!

In other words, if you're a terrorist or a spy, but armed with the right card, your way is open. The stupidest part of the whole process is that the one person who poses the greatest threat to most of these organisations is indeed a thoroughly professional journalist – especially one who has been wrongly denied accreditation.

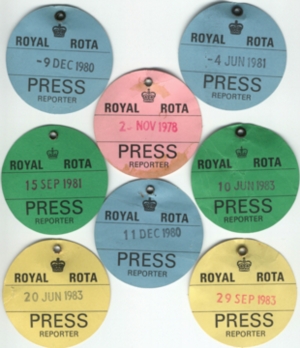

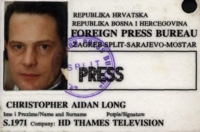

Below is a small sample of the innumerable cards and accreditation I have been persuaded to carry – few of which have ever been respected by anyone other than those who issued them and none of which has been of any significant help to me professionally.

Smoking-gun cards

These cards were first issued by the newly created but unrecognised government of Croatia in October 1991, at a time of intense nationalist fervour during the Serbo-Croatian war.

These cards were first issued by the newly created but unrecognised government of Croatia in October 1991, at a time of intense nationalist fervour during the Serbo-Croatian war.

Right: Issued by the Croat authorities from October 1991

It was never clear whether the card was indeed an official product of Croatia's Ministry of Information – whose name appears on it – and offered no information regarding who was responsible for its issue, when it expired, what rights it purported to offer the bearer or the responsibilities its issuers were accepting. In my case I was not even asked to prove that I was a journalist. I was merely asked to pay a fee at Zagreb's Intercontinental Hotel 'Press Centre'. This became more understandable when it emerged that they were circulating among a large number of the local Croat population, most of whom were not bona fide journalists. The fact that this card (no. 1977) was the 977th card issued within the first few weeks of its issue – and at a time when very few journalists had appeared on the scene – gives some indication of the ease with which so-called journalists were able to acquire them!

The most interesting feature of this card was that in 1992-94 it was universally accepted by ethnic Croats in Bosnia-Hercegovina, which was technically a separate country lying on the other side of an internationally recognised border. In fact it was the only press pass the HVO militias in Hercegovina would officially recognise. This provided ample evidence – if further evidence were needed – of the close proxy status of the HVO to the government of Croatia in Zagreb. This became significant during the subsequent War Crimes Trials in The Hague whenever political and paramilitary leaders attempted to deny or distance themselves from the atrocities committed by the HVO in Bosnia-Hercegovina in 1992-95.

Discredited cards...

This is a rare example of the card issued by the United Nations Protection Force (UNPROFOR) to the tiny handful of journalists working in Sarajevo during the early days of the siege in the Spring and summer of 1992.

This is a rare example of the card issued by the United Nations Protection Force (UNPROFOR) to the tiny handful of journalists working in Sarajevo during the early days of the siege in the Spring and summer of 1992.

Right: A rare card, issued in Sarajevo in the summer of 1992. Under the circumstances it was extraordinary that the UN had the impertinence to issue it all.

It still amazes me that the UN had the nerve and arrogance to issue any card of this sort. In Spring 1992 the first members of a UN monitor group had arrived in Sarajevo to 'observe' the shelling and besieging of the city. As can be seen above, this card was prepared for issue in 03-92. By July 1992, when conditions became 'too dangerous', the monitors withdrew to safety, while a skeleton force sheltered in bunkers at the PTT building and at the airport – leaving the defenceless population of Sarajevo to its fate.

When the situation became a little safer, later that summer, the UN returned to Sarajevo in larger numbers, but offered no more protection than before to either the local population or the handful of foreign journalists who had remained in the city throughout. The UN seemed quite unaware that many of us had managed to work and survive despite their absence and without their little plastic cards – and that many of us had been operating alone throughout the region for almost a year and long before the deployment of the first UN 'forces'.

This card had only one benefit. For a few months that summer (and thanks to admirable people such as Mike Aitcheson and Jeremy Brade of UNHCR) it was possible to cadge lifts in French and British C160 air-freighters whose aid operations linked Sarajevo with Zagreb, Split and Ancona. Although the runway was frequently closed when Serb and BiH forces were firing across it, anyone prepared to risk the nightmare journey via Ilidza and Dobrinje to the shattered airport terminal usually found a helpful and frequent taxi service waiting for them on the tarmac – which did more than anything else to improve UN/Press relationships.

This and later UN press cards made a mockery of the organisation that issued them. They were not necessary to us since, with or without them, journalists continued to roam the front lines – usually in areas the UN itself dared not enter. They offered us no additional protection or assistance, becoming a liability at check-points where they symbolised all the arrogance of a bloated and ineffectual bureaucracy supporting forces more concerned for their own safety than for the people they were deployed to protect. Furthermore, so many of the later versions of these cards came into the hands of non-journalists that they became the universally recognised passport for civilians trying to escape the city via Mount Igman or towards Kiseljac. Sarajevo girls in particular found that a night spent with a UN official could quickly get them a reputation... as a journalist...

The card that changed its mind...

By 1994, two years later, the notion of the UN providing any sort of 'Protection Force' had become farcical. Struggling to protect even itself, the multi-national UN force had become an integral part of the war 'industry' that was tearing Bosnia apart.

By 1994, two years later, the notion of the UN providing any sort of 'Protection Force' had become farcical. Struggling to protect even itself, the multi-national UN force had become an integral part of the war 'industry' that was tearing Bosnia apart.

Usually the UN was a passive observer of institutionalised genocide, terrorism, forced migration and extortion. But often it became an enabling factor in these activities and occasionally it even participated in them.

The UN's 1994 version left ostensibly offered a 'PROtection FORce' to the peoples of former Yugoslavia. When the UN lamentably failed to achieve this mission it crudely stuck a bit of paper over the old slogan and right magically changed its mission to that of 'Peace Forces'. Interestingly the original word 'force' had now become 'forces' – no doubt in the hope that if/when the new assignment failed too, blame could be put on some of the component national 'forces' taking part.

This press card reveals the truth! When even UNPROFOR came round to recognising that it had failed to achieve its mandated objectives, it simply changed its name with breath-taking cynicism to accommodate this unfortunate turn of events. On the card above it can clearly be seen (right) that a sticker has been applied over the old 'UNPROFOR' title and that the organisation now rejoices in its re-birth as the 'United Nations Peace Forces'. As a colleague commented at the time: "Sorry guys, we're clean out of protection... But hey, if you're a lucky survivor, we'll do you peace in a bun with lettuce and mayonnaise".

In time the 'Peace Forces' too became casualties of wishful thinking – peace and protection being the last things it brought to Srebrenica, Mostar, Sarajevo, Bihac or hell-holes of north-eastern Bosnia. It was Nato, infuriated by persistent UN failures, that finally brought about peace of a sort in the summer of 1995 with ground forces led by Britain and France, supported by US air attacks.

For many of us this card recalls one over-riding impression: the arrogance and obstruction many of us faced at the UN press office in Zagreb. Presumably, the principal duty of this office was to inform and assist us in explaining the mission, activities and achievements of the UN in Croatia and Bosnia. But even here the UN shot itself in the foot. Its increasingly tarnished 'image' wasn't improved when the first official contact many visiting journalists encountered in the region was being severely irritated and inconvenienced by UN officialdom.

Hundreds of journalists had often travelled thousands of miles to reach the Balkans and, as a matter of professional courtesy and good policy, headed first for the UN headquarters in Ilica – 207, Zagreb. Seasoned veterans of conflicts around the world often found themselves confronted by a young press officer named Simo Vaatainen, who could delay them for hours or days by querying their paperwork, their professional status or the nature of their relationship with news organisations deemed to be 'recognised'. Worst of all, independent freelancers were almost always turned away.

Perhaps Mr Vaatainen was unaware that some of the best reporting and photography from the Balkans during 1991-95 came from young reporters making their names as independent freelancers, with or without UN accreditation. It was naive to believe that such people would be deterred from reaching their front line destinations just because the UN had refused them a card with a botched sticker on it, all wrapped in a bit of plastic! Having their status disputed seldom warmed such journalists to UNPROFOR.

The UN might have made better use of Mr Vaatainen's formidable talents if they had promoted him to a front line infantry position. Unarmed and single-handed, this Finnish hero of bureaucracy could have stopped whole armies of advancing Serb and Croat forces in their tracks. There he would have discovered that two hundred miles from the safety of Zagreb, UN accreditation proved virtually worthless and could even be a serious liability.

As this picture shows, even British troops in Bosnia, in c.1995, were under UN orders to stop their formidable Warriors politely at check-points and produce their identity cards for any bunch of local lay-abouts who chose to block their path (in this case to a BiH militiaman). Such orders did nothing but damage to the credibility of the UN's peace-keeping forces.

As this picture shows, even British troops in Bosnia, in c.1995, were under UN orders to stop their formidable Warriors politely at check-points and produce their identity cards for any bunch of local lay-abouts who chose to block their path (in this case to a BiH militiaman). Such orders did nothing but damage to the credibility of the UN's peace-keeping forces.

The UN's craven willingness to recognise illegal check-points and de facto internal frontiers – officially out-lawed by the UN itself – lost it any respect in the eyes of Serb, Croat and BiH militias, as well as the civilian population. The troops too were often demoralised by the farce of having to talk their way through, or back away from, bands of armed thugs. All their training and equipment had prepared them to let nothing stand in the way of a military mission.

This was only one example of the many ludicrous consequences of allowing diplomats to dictate the way their armies behave in war. The lesson of this failed policy – as stupid and dangerous as allowing military commanders to dictate to politicians and diplomats – was never learned. It continued throughout the Balkan wars until 1999 and was exported, disastrously, to other trouble-spots around the world. Presumably the UN hoped to disprove the old dictum that 'war is the consequence of failed diplomacy', favouring instead 'war is the continuation of diplomacy by other means'.

The truth is that the UN was never prepared to admit that it had indeed involved itself in a war, preferring to believe that it's forces were deeply engaged in peace!

Unintelligent accreditation...

This accreditation left belongs in a museum of media horrors.

This accreditation left belongs in a museum of media horrors.

It reads:

Mr Chris Long

Freelance for Sky

The above person/s is/are authorised to enter British Forces locations at:

* Krivolak * Prilep * Privolac * Skopje * Veles – * Delete as appropriate

and then, hand-written, it adds:

as and when invited by Unit Press Officer

Valid from: Start Date: 12-iii-99 – To: Finish Date: 22-iii-99

Signed: Paul Sykes (Alan)

Rank: Senior Information Officer

Chief Media Ops, HQ 4 Armd Bde, OP AGRICOLA

The truly ludicrous element about this was that the Press Office at the Skopje headquarters lay inside the base! So how did you get permission or an invitation when you couldn't get inside to request or receive it? Not surprisingly, the staff of seven or so press officers inside the base bemoaned the fact that for weeks at a time they seldom saw a journalist and had little constructive to do.

Amazingly the British Army appeared to think that journalists meekly restrict their enquiries into British military activities for precise periods at precise locations and only when invited! Was there perhaps another pre-printed form somewhere that authorised Serb and KLA fighters to start and finish their attacks on pre-defined military targets, on set dates – but only if 4th Armoured Brigade said it was ready!

In this instance 'Media Ops' was unconcerned that it might insult the intelligence and estrange one its very few British clients. Such documents nearly always reveal a culture of weakness and fear – based on the paranoid presumption that the Press is as dangerous as the opposing forces.

In addition to excluding and alienating the very people dozens of press officers are expensively employed to cultivate, 'media management' of this sort denies an organisation valuable feed-back from journalists who have their noses close to the ground and in places the military cannot reach. It was a great pity that Britain's Ministry of Defence press advisers didn't apply the same excellent approach applied in the vastly more dangerous and sensitive garrison at Vitez, Bosnia, in 1992-95 (see below).

The British army was not a unique case. A few weeks later, in May 1999, Nato unleashed massive air attacks on Serb 'assets' and earned itself world-wide derision when it repeatedly miscalculated the intelligence of the press which reacted with extreme irritation when it found itself being corralled and misled over Nato 'errors' in Macedonia/Kosovo.

In Macedonia, in March 1999, a number of European countries, led by Britain and France, were assembling the multi-national forces that were soon to become Nato's 'Kfor' mission.

In Macedonia, in March 1999, a number of European countries, led by Britain and France, were assembling the multi-national forces that were soon to become Nato's 'Kfor' mission.

Britain's lV Armoured Brigade was technically a 'guest' of the Macedonian government, on exercise under the code-name Operation Agricola. [In truth, as we increasingly suspected, they were only waiting for an air bombardment to soften Serb resistance before they moved north into Kosovo as a formal Nato force.]

A few miles to the north war was raging in Kosovo and the British government and lV Armoured Brigade found themselves in the delicate position of trying to win public approval for what would eventually amount to an expensive, dangerous and long-term commitment to yet another Balkan disaster zone. Good press relations and good press coverage were essential to both Britain's and Nato's causes.

But apart from a handful of local 'stringers' there were, at this early stage, only two or three foreign reporters in Skopje and the surrounding multinational garrisons (for two weeks I was, I think, quite alone!). These correspondents included Christian Millet for Agence France Presse and myself, ostensibly for Sky TV.

We found ourselves in an all too familiar and unhealthy position: vastly outnumbered by hordes of bored Nato press officers who were supposed to be nannying us but who in fact had little to do but hang around the bar and buy us drinks at Skopje's Continental Hotel.

"... Seldom in the field of human conflict has so much alcohol been bought by so many for so few..." – pace Winston Churchill.

Across town at the Panorama Hotel the decision to place the press office inside a military base was proving ludicrous. Journalists had to negotiate tight security with 'secondary accreditation' merely to get a press briefing and then found they couldn't communicate with the outside world because no phone or internet facilities were available to them. Accordingly they had to leave the base and drive two miles into town to report to their news desks from a pay-phone!

Since military commanders seldom trust their press officers much more than journalists, ours were kept largely in the dark and confined to their bases. Inevitably they grew tired of being asked questions they couldn't answer and increasingly tried to give the impression that they knew more than they really did – which only resulted in the increasingly well-informed journalists trading as little information as possible in return. This didn't serve the press officers very well because half their job is to find out what journalists have discovered and to relay this information to their commanders and political masters.

Since military commanders seldom trust their press officers much more than journalists, ours were kept largely in the dark and confined to their bases. Inevitably they grew tired of being asked questions they couldn't answer and increasingly tried to give the impression that they knew more than they really did – which only resulted in the increasingly well-informed journalists trading as little information as possible in return. This didn't serve the press officers very well because half their job is to find out what journalists have discovered and to relay this information to their commanders and political masters.

For a tense month or so we all waited for something to happen – well aware that we would have ring-side seats when Nato celebrated its 50th birthday by going to war for the first time in its history.

We used the time making forays into the snow-bound mountain passes on the Kosovo frontier where, at places like Blasic, we met the first trickle of pathetic Kosovo refugees as they struggled over the twitchy frontier. Little did we imagine that within a couple of weeks these would be followed by many hundred thousand other survivors of Serbian brutality and genocide.

We observed Nato's warm-up and live-firing exercises, establishing good relations with hundreds of young servicemen and made our estimates of how well Nato's multi-national forces might perform together.

Nevertheless, during this 'lull before the storm', Nato's British press officers in Macedonia were so imbued with press paranoia that they sadly lost a valuable opportunity to forge relationships of mutual respect that would have served everyone well later on.

This was surprising because, just five or six years earlier, British forces achieved an excellent rapport with journalists under far worse circumstances at its off-base Press Centre at Vitez in Bosnia. The Vitez base, straddling a front line and frequently under bombardment, never imposed 'secondary accreditation' on visiting journalists who were warmly welcomed in an atmosphere which resulted in copious and generally very positive coverage of British military activities.

Soon after the above appeared I received the following from Diane Paul, a Human Rights monitor in Bosnia in 1995. Her observations are entirely typical of many in her position:

"As a human rights researcher for Human Rights Watch/Helsinki, I (and all my colleagues) were denied any and all accreditation. UNHCR wouldn't give us blue cards because they worried about our tarnishing their image of neutrality – never mind that we reported on abuses by all three sides consistently throughout the war.

We weren't permitted press passes because we weren't bona fide journalists, and that was it. I couldn't get one from IFOR or SFOR either. While I know that the blue cards and UNPROFOR press passes were on the one hand a joke, on the other we were denied access to areas by the UN or the parties to the conflict because we didn't have any passes! Hard to get into Bosnia also because we weren't allowed on the flights. It was unbelievable how the UN actively obstructed freedom of movement – getting through checkpoints, etc. Imagine that the only thing we had were our American passports, which I sure as hell didn't want to pull out – especially in Bosnian Serb controlled territory. For obvious reasons, we didn't want to reveal who we were working for either. So we were sort of stuck, but somehow managed to get in most places. My Maryland driver's license sufficed most times and a number of totally bogus cards with a picture on them worked. I also used documents from friends – in the Catholic and Orthodox church, for example. Some of us did ultimately manage to get blue cards through creative means, which did help in getting into certain areas. The only really positive thing about them, though, was that a lot of Bosnians managed to escape Sarajevo through the international NGOs, which were issuing hundreds of them to help people get out.

After the war, I was really angry when the Croats denied us access to Bosnia over the Sava at several crossing points, claiming that the bridge (built with US money and by Nato forces) were for military use only. Even some Americans with an APC, who tried to get me across, failed. The Hungarian engineer who built one bridge told me they wouldn't even let him across unless he had his ID – even if he was in full uniform – and of course they knew him well. I told him I would be sorely tempted, were I he, to blow the damn thing up. I couldn't believe that the Croat police were given total control over the bridges by Nato. I argued up and down the river with all the Civil Affairs and other people I could find, to no avail. Finally, I drove another two hours and crossed by ferry – for a fee, of course.

My colleague and I had bought some really good Cuban cigars to use as bribes to get through checkpoints, and she wanted to give them to the Croats at the bridge, but there was no way I was going to give them cigars!"

© (1999) Christopher Long. Copyright, Syndication & All Rights Reserved Worldwide.

The text and graphical content of this and linked documents are the copyright of their author and or creator and site designer, Christopher Long, unless otherwise stated. No publication, reproduction or exploitation of this material may be made in any form prior to clear written agreement of terms with the author or his agents.