Lessons Of War

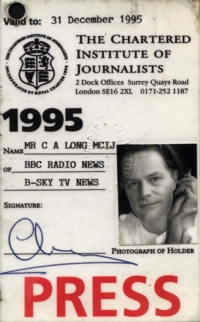

Journal of The Chartered Institute of Journalists – 09-10-1995

a war can go on killing people for a long time after it's all over.'

Nevil Shute — Requiem For A Wren

A personal view of some of the dilemmas facing journalists reporting from Bosnia and similar war zones and disaster areas.

In the Spring of 1989, two years before the Balkan wars supposedly started in Slovenia and Croatia, I was sitting in a cafe in Skopje, Macedonia, chatting with an historian from the local university.

In the Spring of 1989, two years before the Balkan wars supposedly started in Slovenia and Croatia, I was sitting in a cafe in Skopje, Macedonia, chatting with an historian from the local university.

"You know," he said, "we have very difficult times ahead of us – quite soon, I think. And the problem is all to do with maps. People have always wanted the security of ethnic identity, religious identity, cultural identity. It's normal. But when it became possible to mass-produce printed maps in the late 18th and early 19th Centuries we invented a problem. How do you draw a line on a map that allows me to be who I am and lets you, my neighbour, be who you are? Where shall we draw the line?"

A few days later, about 50 miles to the north, troops of the Yugoslav National Army launched a viciously repressive assault on the predominantly Muslim population of Kosovo in its capital Pristina [see Kosovo re the 1998 repeat performance]. The aim was to demolish Kosovo's semi-automonous status within Yugoslavia. The radio and TV station was closed down, telephone lines were cut and, as jets screamed overhead, the population was given a brutal and bloody taste of what Belgrade's long-feared Greater Serbia plan would mean.

A few days later, about 50 miles to the north, troops of the Yugoslav National Army launched a viciously repressive assault on the predominantly Muslim population of Kosovo in its capital Pristina [see Kosovo re the 1998 repeat performance]. The aim was to demolish Kosovo's semi-automonous status within Yugoslavia. The radio and TV station was closed down, telephone lines were cut and, as jets screamed overhead, the population was given a brutal and bloody taste of what Belgrade's long-feared Greater Serbia plan would mean.

Stunned and finding myself the sole foreign correspondent in the region, I rang the BBC's radio newsdesk from Skopje and told them what was happening. They had heard nothing about this from their correspondents based comfortably in Belgrade or from the wire services. I pointed out that since Kosovo's communications had been deliberately cut this was hardly surprising.

It seemed that the BBC was quite unprepared for anything so 'unlikely' after 45 years of Cold War peace in Europe. Hungary in 1956 and Czechoslovakia in 1968 had taught them nothing. The implication was that I was 'mistaken'. My story was not reported and later merited only a paragraph or two in the British press.

Lesson 1: Trust your own judgment even if they don't! Don't assume a newsdesk will appreciate the significance of events on the ground.

Two years later, no-one could have been in any doubt that Europe had a burgeoning war on its hands – no-one except Europe's governments, that is, who from July 1991 stood back and did nothing but observe for almost a year – some would say four years!

Two years later, no-one could have been in any doubt that Europe had a burgeoning war on its hands – no-one except Europe's governments, that is, who from July 1991 stood back and did nothing but observe for almost a year – some would say four years!

This presented journalists with a problem. How could you persuade the print and broadcast news desks that you were witnessing a nightmare of horrors on a daily basis if editors saw their governments were more concerned with Maastricht negotiations and were anyway getting unofficial briefings which referred only to 'local conflicts' and 'ethnic disputes'?

These were editors who had cut their teeth on the Falklands War and the Gulf War with goodies, baddies, plenty of national involvement from the start and regular spoon-fed news briefings from an MOD which positively encouraged the right sort of press coverage. In the end we were reduced to tracking down psychopathic British mercenaries along a 1,000-mile swathe of war zones from Osijek to Dubrovnik in the hunt for a 'British angle'.

Lesson 2: It's far harder for a war-reporter to sell the truth of his story of catastrophe down a crackly phone line (if he can find one) than it is for a Whitehall mandarin to sell an editor fictional reassurances from the comfort of a leather arm-chair in the Reform Club.

From early on the general course of the war was quite predictable. The Serbo-Croatian element of the war in 1991 had been primed by the provocative, nationalist arrogance and racial intolerance of Croats in places such as Knin. This had given Belgrade just the excuse it had been itching for to pull the trigger – to use its massive military power to 'defend' Serbs on Croatian soil and 'acquire' large parts of Croatia in the process – involving widespread ethnic cleansing, the slaughter of civilians, the wholesale destruction of towns and villages and routine war crimes of every sort.

From early on the general course of the war was quite predictable. The Serbo-Croatian element of the war in 1991 had been primed by the provocative, nationalist arrogance and racial intolerance of Croats in places such as Knin. This had given Belgrade just the excuse it had been itching for to pull the trigger – to use its massive military power to 'defend' Serbs on Croatian soil and 'acquire' large parts of Croatia in the process – involving widespread ethnic cleansing, the slaughter of civilians, the wholesale destruction of towns and villages and routine war crimes of every sort.

But it was quite clear to some of us that when winter was over the process would extend into Bosnia-Hercegovina with Serbia and Croatia splitting the proceeds. Yet no-one wanted to know. Who then had heard of Bosnia? So what? Well, it hasn't happened yet!

In Britain, only Channel 4 News (ITN) seemed to see the significance of Bosnia. On 17 December, 1991, I was due to appear to discuss the general situation I had been witnessing in Croatia but asked if I could raise my fears for Bosnia. After some deliberation, and much to ITN's credit, I was allowed to do so – the journalistic significance of this being that a well-reasoned prediction can indeed have its place in the news and analysis of current affairs.

Five months later, in the Spring of 1992, just after Britain and the rest of the world had been bull-dozed by Germany into recognising Bosnia-Hercegovina's independent sovereignty, that country was being torn apart. The world was duly amazed!

Lesson 3: There are, occasionally, times when a prediction based on a news reporter's informed judgment is as valid in news terms as the bald facts he is generally expected to provide.

The Balkan wars have provided a unique training ground for young reporters – staff and freelance alike. While more than seventy of my colleagues have been murdered there, hundreds more have had the opportunity of a lifetime to cut their teeth and make their names, roving freely up and down the front lines – more like Vietnam or Afghanistan and quite unlike the news-managed Falklands and Gulf wars.

The Balkan wars have provided a unique training ground for young reporters – staff and freelance alike. While more than seventy of my colleagues have been murdered there, hundreds more have had the opportunity of a lifetime to cut their teeth and make their names, roving freely up and down the front lines – more like Vietnam or Afghanistan and quite unlike the news-managed Falklands and Gulf wars.

Our duty was to report what we observed, the Who, the When, the What, the Where, and the How – and far too seldom among even the best-trained, to answer that most important question: Why?

But our training often hadn't prepared us for what we found. As if this were a ferry disaster, we applied the 'even-handed', 'fair's-fair' school of journalism. We reported the massacre of ten people in a village and listened to the horrifying testimony of their families and friends. Then we trekked into the hills and politely asked for a rational explanation from the gunners who had mown them down. In Auschwitz, I suppose, we would have asked the man shoving the bodies into the ovens to tell us his side of the story.

Most of us, I think, felt confused by this. On the one hand news desks wanted goodies and baddies to make the story simple for an audience 1,000 miles and 50 years away. On the other hand the same editors were being strangled by the mealy-mouthed, politically-correct dogma which refuses to accept that brutal, old-fashioned, unreasoning and inexcusable evil can and does exist, however much they wish it didn't. By the time this was recognised, in the case of the Tutsis and the Hutus in Ruanda, it was too late for Bosnia.

Lesson 4: Occasionally a time may come when a journalist has to make it clear that even-handed reporting is only obscuring an ugly truth.

But truth is a rare commodity in the Balkans.

But truth is a rare commodity in the Balkans.

Few regions have had, down the centuries, so little to be proud of, so much to regret, so much guilt to live with and so much innocent blood on its hands – all its hands, regardless of race, religion or culture. It's far easier to adjust the record, blame the others and get together with ethically 'pure' neighbours to purge the uncomfortable evidence of the past with ethnic 'cleansing'.

It was this fundamental dishonesty, as much as anything else, which made the war so hard to explain.

"We're liars," a Bosnian colleague told me in November 1992 as we drove out of Sarajevo, up the front line and through the devastated Croat-Muslim war zones. "We lie to each other, we lie to ourselves. Why? Because we don't like the truth, of course!" But I had to believe him when he said he knew the safest route to Split!

It's hard to establish the truth in a land where everyone has their own opposing versions of simple events or even of historical facts (from which, incidentally, they appear to have learnt very little) and where people can look you in the eye and lie through their teeth about anything and everything from most trivial to the most significant. It was for this reason as much as any other that Lord Carrington resigned from his peace-making role at the London Conference in 1993.

Wearily we reported the umpteenth solemnly sworn ceasefire agreement in Geneva – while adding that it would mean nothing on the ground because local commanders had told us so. And time after time our news desks would only report the Geneva end of the story, as if it were the word of God, because for 50 years power-broking was associated in newsroom minds with plush hotels in capital cities – not with rubbish-strewn gun batteries on dismal hillsides with barrels aimed at market squares. Thus we appeared to be the naive reporters of yet another false promise!

Time after time we risked life and limb to visit alleged scenes of horror only to discover that it was a set-up or self-inflicted in order to win sympathy. But if we hadn't continued to investigate such reports, camps like Omarska and the discoveries of the mass slaughter of civilians and mass-graves would never have been made either.

Lesson 5: Be very, very sceptical – but the moment a reporter becomes cynical it's time to go home.

As always there are two major elements in the job: getting the story and then delivering it. In the UK delivery is usually the easy bit. One of the paradoxes of the Balkan wars is that just when we were equipped with the full might of electronic information technology, it ran straight into the buffers of a primitive and usually non-existent telephone system.

As always there are two major elements in the job: getting the story and then delivering it. In the UK delivery is usually the easy bit. One of the paradoxes of the Balkan wars is that just when we were equipped with the full might of electronic information technology, it ran straight into the buffers of a primitive and usually non-existent telephone system.

I chose not to be virtually pinned down in one place by a cumbersome satphone and took my chances with sound-recording equipment and a Mac laptop making sure I could charge it from a car battery and had learnt the dirty arts of hot-wiring comms equipment to other peoples' phone lines.

My single biggest problem has been finding working phone lines for radio reports, live two-ways, copytakers or data-transfer to newsroom systems. After driving 50 hairy miles to reach a phone-line, it's hardly ever capable of supporting fax, data or e-mail. Furthermore, there's often little understanding in UK newsrooms of the immense difficulties reporters face in just getting a call through.

In October 1991, colleagues and I aboard the M.V. Slavija, were trying to reach the besieged city of Dubrovnik, when we were faced with the all-too-real threat that we would be sunk with all hands by Admiral Brovet's gunboats. Having battled for two hours to get to the one ship-to-shore phone and spent 20 minutes patching a call through to the Evening Standard via Brindisi and Rome, the copytaker went off for lunch in the middle and his successor wanted to know how I spelt 'Dubrovnik'.

In June this year, three attempts to get the Reuters' London News radio newsdesk to call me back, while the Rapid Reaction Forces made their historic landing before my eyes at Ploce, were fielded and ignored by a girl on 'work experience'!

Sometimes there's nobody at all capable of receiving a news story or you can drive 70 miles across the front lines to meet a live two-way booking with B-Sky, and then not get their call – only to discover the next day that they changed the schedule without bothering to tell you.

Interestingly, I have never had these sorts of experiences with any North American or other European news organisations.

Lesson 6: Don't risk one hair of your head unless you're sure you can get the story back and never let a news organisation's 'disorganisation' put you at any further risk.

After a while, the effects of stress in war-zones get serious. You are probably the last to know this, however. Your 'fear and flight' autonomic system is on alert all the time, even when you're sleeping. In normal circumstances you might use its massive chemical charge of adrenalin, noradrenalin, cortisols and endorphins for a few seconds once or twice a month. In war zones this self-protective 'Rapid Reaction' response floods the system continuously with the equivalent of mixed doses of heroin, cocaine, marijuana, alcohol, uppers, downers, etc.

After a while, the effects of stress in war-zones get serious. You are probably the last to know this, however. Your 'fear and flight' autonomic system is on alert all the time, even when you're sleeping. In normal circumstances you might use its massive chemical charge of adrenalin, noradrenalin, cortisols and endorphins for a few seconds once or twice a month. In war zones this self-protective 'Rapid Reaction' response floods the system continuously with the equivalent of mixed doses of heroin, cocaine, marijuana, alcohol, uppers, downers, etc.

Among the side effects are paranoia, irrationality and alternating moods of aggression and lethargy – all coupled with an inability to recognise the syndrome. In fact they are all quite normal reactions to quite abnormal circumstances.

However, a war zone, with all its dangers and horrors, can soon become familiar and so appear 'normal'. Journalists who, above all others, choose to think that they are the guardians of cool, rational assessment in the midst of insanity are particularly vulnerable to this self-delusion.

Compounding the illusion are local people who are similarly or often worse affected and go about their lives with a deceptive appearance of normality – chatting with friends on a street corner. What else should they do when they might not see each other again and can in any case be hit any time, anywhere?

Compounding the illusion are local people who are similarly or often worse affected and go about their lives with a deceptive appearance of normality – chatting with friends on a street corner. What else should they do when they might not see each other again and can in any case be hit any time, anywhere?

The first time you see red-hot shards of shrapnel spinning at the speed of sound and slicing the gossiping group into butcher's meat, you might think it an obscene aberration. It is, of course. But it's quite 'normal' in the Balkans today. It's easy to begin to accept that is not 'abnormal' either.

British troops with all their weapons, armoured vehicles, communications, training and back-up are expected to face only six months before they're withdrawn. But some journalists spend years exposed to this institutional insanity – and no, I'm not talking about newsrooms!

I find that the periods of time I can stay there get progressively shorter as the tours and the years go by. Of the many who have been killed there, I suspect a lot stayed too long.

Lesson 7: Don't underestimate the sickness of war. It's insidious and it'll sicken you in more ways than you think. The day a friend suggests you need a break and you snap back saying he's wrong is the day you should go home for a good long break.

The piece above was kindly posted on the Tribunal Watch newsgroup on 10-02-98 by Nalini Lasiewicz with the following encouraging remarks:

"...journalism is a major component in all our lives and the lessons that many journalists have learned from this conflict will, I believe, work to our benefit in future conflicts. Here is another article from Christopher Long which explains some of the challenges and problems in the field, from one writer's perspective. As people berate the journalists who reported under such horrible circumstances, in this and other war zones, I hope that they will realize that maybe some of them do a better job than we've given them credit for. We ought to remember those who died covering this war as well. It's so easy to criticize, it's harder to understand the difficulties of this work. – Regards, Nalini Lasiewicz"

© (1995) Christopher Long. Copyright, Syndication & All Rights Reserved Worldwide.

The text and graphical content of this and linked documents are the copyright of their author and or creator and site designer, Christopher Long, unless otherwise stated. No publication, reproduction or exploitation of this material may be made in any form prior to clear written agreement of terms with the author or his agents.