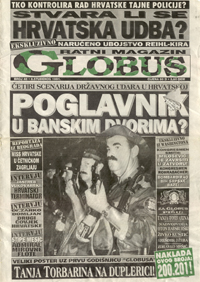

The Slavija Convoy & Besieged Dubrovnik

Globus (Zagreb) – 08-11-1991

One of the most bizarre episodes in the Serbo-Croatian war occurred in November 1991 when a Dalmatian car ferry led a convoy of little boats on a Croat mission to break the Serbian blockade of the besieged port of Dubrovnik.

One of the most bizarre episodes in the Serbo-Croatian war occurred in November 1991 when a Dalmatian car ferry led a convoy of little boats on a Croat mission to break the Serbian blockade of the besieged port of Dubrovnik.

The vessels were stopped and threatened with sinking by JNA armed patrol boats – but achieved their mission nevertheless.

This was a provocative and dangerous escapade that nearly ended in catastrophe. Evening Standard reporter Christopher Long was on board.

By Christopher Long

See end of page for reports to the London Evening Standard

T

he extraordinary convoy which left Rijeka for Dubrovnik last Tuesday contained everything I most love about the Croatian people and many of the things which make me most despair for their future.

The original idea was magnificent, an immediate emotional response. It was organised with passion in just a few days. The plan was for the Slavija and her convoy of 38 small ships to carry the message of solidarity and the practical aid that was so desperately needed in Dubrovnik. It was to be a defiant symbol of the aspirations of a free people to travel freely across its own territory and waters. It was supposed to attract the attention of the world to what is happening in Croatia and, above all, it came from the heart.

The departure from Rijeka on Monday 28 October was, in some ways, the start of Croatia's Dunkirk. But by Friday 1 November, as we were returning exhausted from our very dangerous confrontation with Admiral Brovet's navy and the very emotional meeting with the tragic people of Dubrovnik, the convoy had been high-jacked and sabotaged. Not by the JNA, you must understand. It had been high-jacked by those age-old characteristics of the Croatian people which I love and sometimes hate.

The departure from Rijeka on Monday 28 October was, in some ways, the start of Croatia's Dunkirk. But by Friday 1 November, as we were returning exhausted from our very dangerous confrontation with Admiral Brovet's navy and the very emotional meeting with the tragic people of Dubrovnik, the convoy had been high-jacked and sabotaged. Not by the JNA, you must understand. It had been high-jacked by those age-old characteristics of the Croatian people which I love and sometimes hate.

A journalist from Zagreb asked me on that return trip whether I thought the convoy had been a success.

"A success for whom?" I asked, and he looked a little puzzled. Was this a success for the people of Dubrovnik; or for the organisers; or for the relief workers; for the military and political position of Croatia; for the journalists; or for world opinion; or for the political ambitions of Mr Mesic; or for the publicity value for Theresa; or for the self-satisfaction of writers, artists, poets, intellectuals...?

I joined the convoy at Split on Tuesday after a nightmare 13-hour drive from Zagreb with Tonko Vulic, a Globus photographer. The drive, of course, was via Ljubljana and Rijeka. You know when you are in Slovenia because the Slovenes are becoming very Austrian: they paint the tank barricades a tasteful shade of green and provide unhelpful border-guards to demand passports, press-cards and camera permits. They behave as if Slovenia has been an independent and war-free country for centuries: haute-bourgeousie who find gypsies have moved into the house next door. Was this really the country I worried about in July 1991?

I joined the convoy at Split on Tuesday after a nightmare 13-hour drive from Zagreb with Tonko Vulic, a Globus photographer. The drive, of course, was via Ljubljana and Rijeka. You know when you are in Slovenia because the Slovenes are becoming very Austrian: they paint the tank barricades a tasteful shade of green and provide unhelpful border-guards to demand passports, press-cards and camera permits. They behave as if Slovenia has been an independent and war-free country for centuries: haute-bourgeousie who find gypsies have moved into the house next door. Was this really the country I worried about in July 1991?

Rijeka was a blaze of lights, the last we saw for 500 kms. We drove down the coast to the tiny ferry station which crosses to Pag Island and persuaded the brave but frightened crew to sail through the dark especially for Globus. Ten days before the ferry had been attacked by JNA planes. Now the boat is painted grey and as we stood on the bridge with the captain we all pretended to be looking at the beautiful stars.

Left: The author, Christopher Long, on a long section of mined road just north of Zadar on the Adriatic coast on the night of 28/29 October 1991.

Left: The author, Christopher Long, on a long section of mined road just north of Zadar on the Adriatic coast on the night of 28/29 October 1991.

He had driven at night with Globus photographer Tonko Vulic from Zagreb down the Dalmatian coastal road, some stretches of which were effectively the front line between the warring Croat and Serb forces. Gospic was then in Serb hands and the coast between Karlobag and Sibernik was well within Serb shelling range (some parts parts being fully under Serb control) which effectively cut Dalmatian Croatia into two halves.

This coast road was, before the 1991-92 Serbo-Croat war, the main artery serving the packed tourist resorts full of economy-class German industrial workers. In November 1991, however, the author saw not a single vehicle apart from the burnt-out wrecks destroyed in cross-fire and occasional battered lorries with cross-hair headlights carrying ammunition up to the Croat HVO positions. Much of the road was mined and pot-holes and shrapnel from mortars and shell impacts made driving particularly hazardous, since the journey had to be made without headlights and at high speed in order to reduce the risk of being the target of JNA gunnery.

To avoid driving into the Serb front line, the author persuaded the small car ferry at Prizna to sail for Zigljen on Pag Island. The ferry captain was particularly courageous because his vessel in the moonlight made a perfect target for Serb aircraft. They then crossed the badly damaged Pag bridge back onto the mainland, taking care to avoid mines on the coastal road between Zadar and Sibernik, before arriving in Split in time for the Slavija's departure.

We drove through Pag Island and the first car we saw was a tiny Yugo with four fat, cold policemen trying to sleep. Their job was to freeze to death if necessary in order to stop anyone using the Pag Island bridge back on to the mainland. We wanted to cross. They wanted to close their car window as quickly as possible. OK, they said, and we crossed the bridge driving very carefully round the huge hole the JNA have created by bombing the middle of it.

From there we drove through and around the war-zones of Zadar and Sibernik. This drive is a strange and eerie experience. The roads are deserted and the only sign of life is the soldiers (whose soldiers?) who suddenly emerge from the dark demanding passports and press-cards. Again no lights, no cars, no signs of life. Does anyone live here? They must do because the news tells us that people are dying here.

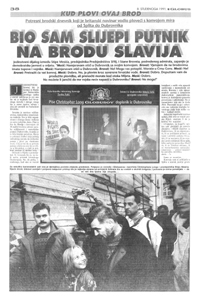

As the M.V. Slavija left the port of Split for Dubrovnik, the author and Susana can just be seen leaning against the rail with the ship's funnel immediately behind them.

As the M.V. Slavija left the port of Split for Dubrovnik, the author and Susana can just be seen leaning against the rail with the ship's funnel immediately behind them.

We wondered if we would be joining the dead as we entered stretches of road marked as mine-fields and I walked slowly ahead of the car with a pocket torch, signalling to my infinitely braver driver where to make snake-like S-bends for hundreds of metres. We were never sure whether the deeper, buried mines were still in position.

In the end journeys like this make you laugh. There is nothing, no-one, to remind you that you are driving through the known world. Every few hundred yards are wrecked cars, the debris, the gun positions, the holes in the road and a total absence of anything human or humane. Here in Croatia I have often felt I was on another planet. On the road to Split we were in another galaxy.

The first thing that worried me as we watched the ship being loaded on Tuesday was how very, very little food and medical aid we were carrying to Dubrovnik. The Slavija's huge car-deck had a couple of trucks and a pathetic collection of oranges, onions, oil-drums, plastic water containers and boxes of food addressed to individual families in Dubrovnik. There was almost enough room for a Hajduk v. GOSK football match in the space that could or should have contained, for example, the water purification and desalination equipment which is so desperately needed in Dubrovnik.

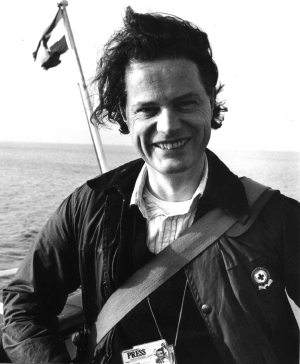

Ed Vuliamy (left), correspondent for The Guardian and the author, Christopher Long for London's Evening Standard, aboard the M. V. Slavija in the Adriatic in October 1991. A few days earlier the vessel had led a convoy of small vessels carrying humanitarian aid to the besieged city of Dubrovnik. Croat organisers described this as an heroic 'human rights' mission. But many foreign correspondents who accompanied the convoy into its confrontation with JNA gunboats regarded the trip as unnecessarily reckless and confrontational. A catastrophe at sea was only narrowly averted.

Admittedly the car ferry Balkania left Split before us loaded to capacity with Red Cross and other aid, while many of the small convoy boats were packed with supplies as well. Nevertheless, the 50-60 foreign journalists and film crew probably weighed more than the Slavija's freight cargo. Were we what the people of Dubrovnik really needed? And did they really need the dozens of hungry politicians, self-important writers and poets, the ageing singers and cafe politicos?

Perhaps they did. Ten thousand people from Split thought so and packed the quay for a deeply emotional and moving demonstration of solidarity. "Vukovar! Vukovar," they cried. "Theresa! Theresa!" they begged. "Stipe! Stipe Stipe!..."

As the crowds lined one side of the ship, Susana stood alone on the other side looking out to sea. She had told her father in Split that she might not come home tonight. She was surrounded by everything she could possibly carry to her sister in Dubrovnik. I asked her who she was. She didn't reply immediately. She was crying quietly in the dark.

We stood together holding hands. She thanked me for joining the convoy and I felt very small. Thank God there were several hundred Susanas in addition to the travelling circus waving goodbye for the cameras as the ship sailed into the night from Split.

This is one of the three JNA coastal gunboats that stopped and threatened the Slavija.

This is one of the three JNA coastal gunboats that stopped and threatened the Slavija.

For several hours the forward and rear gun-turrets of all three vessels were trained on the bridge as Stipe Mesic – still officially president of Yugoslavia – negotiated by ship-to-shore phone with the JNA's Admiral Brovet in Belgrade.

Seldom can a head of state have found himself bargaining at gun-point for his own life and free passage in his own waters. Still more seldom that the guns threatening to sink him were theoretically his own to command!

The main drama of the voyage, of course, was the confrontation with Admiral Brovet's navy beyond Korcula. Everything about this was bizarre.

When has a captain (who is legally responsible for the safety of his passengers, crew and ship) ever sailed into a war-zone with the unenviable pressure of having his country's President standing beside him and determined to sail forward? When has the President of a non-existent country ever stood on the bridge of a ship and negotiated with an 'enemy' of which he is technically the Supreme Commander? When has a Supreme Commander negotiated with his navy while twin pairs of 40mm guns are aimed at him by what are technically his own patrol boats?

The journalists went mad as the negotiations stretched on. Hours of negotiation between Mesic and Brovet were interpreted and summarised by the international press roughly as follows:

Mesic: I intend to go to Dubrovnik with my convoy.

Mesic: I intend to go to Dubrovnik with my convoy.

Brovet: I believe you have guns and soldiers on board.

Mesic: I intend to go to Dubrovnik.

Brovet: No. I can shoot you out of the water. You may go to Montenegro.

Mesic: No.

Brovet: I shall search your convoy.

Mesic: OK, but I am sailing through sovereign waters of Croatia.

Brovet: OK, I give you permission to proceed but you must spend the night near the island of Mljet.

Mesic: OK, but can you guarantee that the army will not attack me in Dubrovnik?

Brovet: No.

The journalists were desperate to report the news to London, Vienna, Rome, The Hague, etc... This was difficult to achieve. Someone had forgotten to deliver or put onto the ship the satellite communications equipment the organisers had begged the Croatian Ministry of Information to provide. So, dozens of journalists fought for the single ship-to-shore radio telephone – the same phone the captain and Mesic needed for their negotiations between the Slavija, Zagreb and Belgrade.

Each call takes 5-10 minutes to establish – if you are lucky. You are luckier still if your news desk can hear what you're saying.

And please don't think London is perfect. My newspaper's copy-taker seriously asked me to spell 'Dubrovnik'. The word Dubrovnik has never been spelled before the way I gave it to him.

Did the organisers really want the world to know what was happening? Of course they did. But it would have helped if the announcements on the ship had also been made in English or some internationally recognised language the foreign journalists could understand. Several formal requests for translations were made and ignored. Mrs Separovic told me that if I did not speak Croatian then I should not be on the Slavija at all. Mrs Separovic is the wife of the Foreign Minister, of course.

Did the organisers really want the world to know what was happening? Of course they did. But it would have helped if the announcements on the ship had also been made in English or some internationally recognised language the foreign journalists could understand. Several formal requests for translations were made and ignored. Mrs Separovic told me that if I did not speak Croatian then I should not be on the Slavija at all. Mrs Separovic is the wife of the Foreign Minister, of course.

At least Mr Mesic and Admiral Brovet understood each other. We journalists didn't quite know which of them was the winner. Mesic had shown admirable determination and courage and seemed to have got what he wanted. But Admiral Brovet appeared to have 'granted permission' for the convoy to proceed. A brief and purely technical search took place on the Slavija though, according to captains of some of the smaller ships, the 'Cetniks' who searched their boats were much less technical and far more brutal.

There was an atmosphere of jubilation on board among the organisers, the celebrities and the cafe-politicos as we sailed south for Mljet. I was pleased that there were dozens of quiet, thoughtful and deeply worried Susanas on board. They reminded me that this was not a holiday cruise through the Dalmatian islands. They were not worried for themselves, of course, but only about what they would find in Dubrovnik as we steamed steadily south.

But perhaps they should have been a little bit worried for themselves. An attempt was made on Wednesday to test one of the life-boats – the one on the starboard side nearest the bridge. Unfortunately it didn't work and the crew, sparing themselves any more disappointment, decided not to test any others.

The life-rafts had a 'Last Checked...' label on each one, but someone had forgotten to mark the date. Personally I didn't mind: if we were sinking while we slept in our cabins the announcements would probably have continued to have been made in Croatian only.

Left: This badge dates from Spring 1992, six months after the Slavija convoy. These badges were hand-made by nuns for the naval militia of Dubrovnik who were responsible for coastal defence and resistance against the Serb/JNA navy.

Left: This badge dates from Spring 1992, six months after the Slavija convoy. These badges were hand-made by nuns for the naval militia of Dubrovnik who were responsible for coastal defence and resistance against the Serb/JNA navy.

The author was presented with this one when he spent four days visiting the city's coastal defences around Colorino Bay, its front line defences at the former Belvedere Hotel and particularly the fiercely defended trench positions behind the old Imperial Fortress on the mountain top.

We sailed into Dubrovnik at dawn on Thursday. It was one of the most extraordinary arrivals imaginable. We looked for the damage in and around Babin Kuk as the town slept. We slid up to the quay where about 25 dazed civilians and another 30 police and armed militia watched us quietly.

The reception was at first restrained. Mr Mesic decided not to leave the ship immediately and ten minutes later, sure enough, the crowds gathered. It was true! The convoy had arrived. The truth dawned slowly but with a heart-felt, almost heart-breaking, gratitude.

The Susanas wept in the arms of loved-one. At this moment everything had been worth the risks. I admired Mesic for his leadership. I admired the organisers for their faith. I admired the Croatian people for their compassion and most of all I admired the captain for his courage in taking responsibility for the whole venture.

I also admired, as ever, the speed with which my colleagues found telephones and the precious few lines that worked, getting the news to the world in minutes. [In my case, the one working phone I managed to find was quickly commandeered by Alan Little who was a stringer for the BBC, who no doubt thought that the Evening Standard took second place!]

Dubrovnik is a diamond lying in shit. The shit is surrounded by vultures on the hills. The diamond still sparkles. I wondered what the vultures were thinking. Perhaps the people of Dubrovnik looked like rats from under the JNA flags on the two hills that command the east and west of the city. It's hard to remain journalistically objective in these circumstances.

Well, you know the situation: the city is under siege. They have no drinking-water, no electricity and most people now have no way of heating food or boiling water. The windows are all taped. There are Croatian Guards behind sand-bags everywhere. The people have been offered weapons to defend themselves but many have given them back. What good would they do? Wouldn't they be tempting providence?

The town is full of families who have been forced back from towns and villages around Dubrovnik. The mayor told me he has records of about 40 deaths and 400 wounded in the region. It takes time for the statistics to be collated. Maybe it is 50 dead by now (last week), he said. About half the deaths were civilian. A Croatian Guard doctor said most of the deaths resulted from car accidents and shrapnel. In 30 days he had seen no one killed directly by a bullet. Reporters who visited a hospital were appalled by the conditions. Why has no one brought the desperately needed water purification equipment, I was asked. Don't they know about the dangers of cholera, typhus fever, etc...

Spiralling inflation was one of the immediate effects of the outbreak of war in Slovenia and Croatia in the summer and autumn of 1991. This 10 Dinar bank note has been 'over-stamped' to read 100,000 dinars. Although this note was a 1992 Bosnian concoction, cities such as Dubrovnik also found that barter or foreign cuurencies were the only valid currencies. Under old Yugoslav law it was a serious offence for ordinary civilians to trade in foreign currencies. Nevertheless, everyone was desperately converting increasingly valueless dinars into German deutschmarks or US dollars. The deutschmark soon became the staple currency throughout the old republic.

A year later, besieged towns such as Mostar, in Bosnia-Hercegovina, were reduced to printing their own siege currency – see example above – again in deutschmarks.

The hospital made a stark contrast with the Town Hall where I interviewed the mayor. It's as clean, as organised and as civilised, as a hospital in London. In the reception rooms there were smart receptions for the VIPs. I left.

Outside, the streets were in carnival mood but I walked away to the old port. There the atmosphere was different. Am I right in thinking that the mass of the poorer people were less impressed by our arrival? For them the daily effort of queuing at the water-carts and finding food for the day leaves little time for visiting celebrities. They were polite but restrained.

[Little did I know that the following year I would be sheltering alongside the same people in undergound wine cellars near the old port as the Serb/JNA postions on the nearby cliffs attacked the southern end of the town. Mostly women and children, the crying of children and the fetid smell of urine and fear was greatly relieved by young children clinging to their precious bicycles as they peered into the darkness and the source of shooting while enthusiastically asking whether I knew about this or that famous rock band or if I had ever been to the Hard Rock Café in London]

Everywhere I went people were asking, with great dignity, for help:

Everywhere I went people were asking, with great dignity, for help:

"Please tell the world about Mihovil Ercegovic and his son Marko. They were arrested in mid-October in Slano. They were taken to Trebinje and then to Bileca. He owned the Sesame Gallery. Please tell the world."

"Please help me! Our friends Marin Gozze and Vesna Delic were taken from the Argos Restaurant on October 28 in Mali Zaton. We don't know where they are. Please, can you help?"

The author, Christopher Long, on the outward journey to Dubrovnik aboard the MV Slavija. The Globus photographer, Tonko Vulic, remained behind in Split.

Later, during lunch with Vesna and Jadran Gamulin, at Kolorina-4, their friend Pinki rang. I spoke with him for half an hour. He was desperate to talk – starved of conversation. Pinki, an actor, lives in Mokosica, just a couple of kilometres from Dubrovnik. The town had a population of 10,000 in July. Today there are about 500 mixed Serbs and Croats.

"I have friends I never knew I had," he explains. "You see, I can't move from here. The JNA controls the bridge. We are cut off from Dubrovnik and Dubrovnik is cut off from Croatia and Croatia is cut off from the world. Please, ask my friends to ring me. My number is 50-451071. Tell Nono Seculic to ring me too."

Pinki, if you are still there, your message has been delivered.

After speaking to Pinki, Vesna and Jadran made lunch for me and a Dutch colleague. It was the most difficult meal I've ever had. They used almost the last of their bottle of gas to cook the last meat they had. Normally they eat rice and the surprisingly large quantities of frozen chicken which is expensive but easy to find. We drank wine because there's no water. We admired the view of the sea (where they wash) from the windows which we noticed were directly in line with the JNA hill-top positions across the city. Vesna & Jadran, I'll never forget that lunch.

Before lunch we had witnessed a remarkable development. It had seemed, as we travelled south to Dubrovnik, that Stipe Mesic was becoming more and more the centre of events and attention. His speeches and interviews became increasingly assertive. It seemed to me that he had recognised that this was a moment of destiny. By the time he had finished speaking in Dubrovnik I wondered if I was watching the beginning of the end of Tudjman and the beginning of the beginning of Mesic. Perhaps I was just carried away by the spirit of the moment. We'll see.

Before lunch we had witnessed a remarkable development. It had seemed, as we travelled south to Dubrovnik, that Stipe Mesic was becoming more and more the centre of events and attention. His speeches and interviews became increasingly assertive. It seemed to me that he had recognised that this was a moment of destiny. By the time he had finished speaking in Dubrovnik I wondered if I was watching the beginning of the end of Tudjman and the beginning of the beginning of Mesic. Perhaps I was just carried away by the spirit of the moment. We'll see.

The author, Christopher Long, on the return journey from Dubrovnik aboard the MV Slavija. At Split he picked up his Globus photographer Tonko Vulic for the final leg of the journey to Rijeka.

I had found him a charismatic, immediately attractive man. But I cannot understand Croatian – let alone the subtleties of his speeches. I know nothing about him apart from a shared preference of particular brands of cigarettes (he consumed a large number of my Silk Cut), his relaxed and easy manner with me (whenever his Rambo body-guards would allow) and our shared affection for a little girl aged about six who attached herself to us during the thanksgiving mass in the cathedral of Dubrovnik. Sometimes she held his hand and kissed him. Sometimes she held my microphone and cuddled me. She proudly told me she hadn't bathed for two weeks. She didn't need to tell us that. She was dirty and she was beautiful.

That night, Thursday, the JNA decided to shoot at us near the Slavija and succeeded in injuring a five year-old child. The following morning, two hours after we left Dubrovnik at dawn, they attacked again. This time they killed four small children and the adult who was driving then. Pray God that my dirty little friend was not one of them.

The return trip was reasonably uneventful. Mrs Separovic objected very strongly when other organisers allowed a few mothers with tiny babies to return with us. This was contrary to the spirit of the convoy, she said. Apparently she left the convoy at Korcula and so was not able to witness the even greater crowds which came to welcome the convoy at Split and Rijeka.

The return trip was reasonably uneventful. Mrs Separovic objected very strongly when other organisers allowed a few mothers with tiny babies to return with us. This was contrary to the spirit of the convoy, she said. Apparently she left the convoy at Korcula and so was not able to witness the even greater crowds which came to welcome the convoy at Split and Rijeka.

On board the MV Slavija, returning to Rijeka, are: left Christopher Long, right photographer Tonko Vulic, and between them Tomoslav Skalamera, a shell-shocked doctor, being evacuated after spending too long on the Dubrovnik/Cavtat front line south of the besieged city.

The welcomes were truly magnificent. Dozens of tugs and fire boats escorted the Slavija into Rijeka on Saturday morning. The Mothers of Croatia were there with the town band and the mayor and a crowd of about 8,000. "Vukovar! Vukovar!" they shouted. "Stipe! Stipe! Stipe!..."

We stayed to watch for a while and then drove back to Zagreb.

I felt confused. Croatia had achieved a small miracle – a Balkan Dunkirk. And yet... why was there just something about the whole thing that made me feel uneasy?

The Dubrovnik Blockade – The Evening Standard – 29-10-91 – 13-11-91

The Evening Standard 29-10-1991

By Christopher Long aboard the MV Slavija in Dubrovnik

An extraordinary cargo of Red Cross relief workers, food aid and journalists was this morning sailing from the free Croatian port of Split to the Serbian-besieged city of Dubrovnik.

An extraordinary cargo of Red Cross relief workers, food aid and journalists was this morning sailing from the free Croatian port of Split to the Serbian-besieged city of Dubrovnik.

The vessel, Slavija, has received instructions to join a convoy before midnight tonight. If it does not do so there is no guarantee of its safety. A similar relief vessel was attacked last week.

Evening Standard reporter Christopher Long on board the ship said: "If the vessels do not get into Dubrovnik soon there is a greater chance they will be attacked. We're not that confident to tell the truth."

He dodged mines and talked his way past nervous, untrained soldiers on an 800 km overnight drive through abandoned villages to join the ship.

"The roads are littered with the debris of heavy fighting and many warnings of mines. I walked in front of the car at various stages to guide us away from the mine craters in the road."

"You get stopped by young soldiers aged 17 or so who are trying to look controlled but are very nervous."

"There were no cars at all on the road except for many, many hulks crushed by tanks. There are horrendous pile-ups. All the villages on the coast appear deserted, the houses have their windows taped up and there are no animals around at all."

His midnight dash with a Croatian photographer took them from Zagreb via Rijeka, Zadar and through the Sibernik area in order to reach the vessel and skirt around the Serbian and Croat forces which are still in an armed stand-off around Sibernik and Zadar.

The Croatians were so keen for journalists to reach Dubrovnik to witness what they describe as a human disaster that a 750-ton ferry made a special sailing for the Evening Standard team between the coast of Croatia and the island of Pag to avoid further fighting which is imminent at any time around the northern sector of Zadar.

The relief vessel is receiving reports from the Croatian government – which is very anxious to persuade the Dubrovnik population to remain in the city and not to desert it – that Serbian naval commander Admiral Brovet is threatening to sink the ship...

The Evening Standard – 30-10-1991

... Tension on the Slavija continues although a search for weapons on board by Yugoslav (JNA) national navy officers was completed without incident.

Other ships in the 38-strong convoy are now being searched.

A small gunboat at one stage threatened the Slavija and her 1,400-1,800 civilian passengers – its forward gun aimed at the bridge where Yugoslav President Stipe Mesic, the wife of Croatia's foreign minister and the Croatian minister of justice were standing.

The attempt to enter Dubrovnik appears to be a deliberately provocative, symbolic act which has potentially disastrous consequences.

A very small consignment of food and medical aid is stored below decks but the passenger list is a 'Who's Who' of Croatian celebrities, intellectuals and journalists.

There is now a stalemate while we await the JNA's next actions.

This is dangerous and can bring no great benefit to Dubrovnik...

The Evening Standard – 31-10-1991

... Yugoslav president Stipe Mesic, under threat of a hail of shells, today successfully negotiated free passage for the first ferry to break the naval blockade of the besieged city of Dubrovnik, delivering vital aid to its people.

... Yugoslav president Stipe Mesic, under threat of a hail of shells, today successfully negotiated free passage for the first ferry to break the naval blockade of the besieged city of Dubrovnik, delivering vital aid to its people.

I was aboard the small ship Slavija carrying Mr Mesic, a Croat, and the wife of the Croatian Foreign Minister as it led other vessels into the Adriatic port to deliver food and medical supplies.

As the ships sailed through the blockade, President Mesic told me: "We have to break the blockade and it must remain broken".

"We want to demonstrate to the world the situation in Dubrovnik today. The aim of the convoy is to return the city of Dubrovnik to its citizens."

Originally our flotilla had been refused permission to land amid claims that it was carrying weapons.

Heavy shelling of Dubrovnik preceded tense negotiations between Admiral Brovet, in charge of the Yugoslav naval forces, and President Mesic. But finally we were allowed to pass.

The navy boarded the vessels which set out from the Adriatic port of Split and searched them for weapons 50 miles from our destination.

While heavily-armed Croatian forces mass on the outskirts of the city and gunfire echoes through the narrow alleyways, there are 50,000 citizen trapped in the centre where electricity has been cut off and water supplies are running low.

We docked at 6.25 am local time and were met by 50 military police and local militia. But as news of the blockade-runners spread throughout the town, crowds gathered at the docks.

They looked surprised to see us and many became emotional. The plan is to take back to Split those who are sick and suffering and otherwise unable to leave. The flotilla has taken more than a day to cover what would normally have been a three-hour journey. Up to the last moment when we moored up, we feared we might be shot out of the water.

We had been forced to wait until first light before going in for fear the army would attack. The ferry's captain, Damir Jovanovic, warned the other vessels over the radio: "We don't want some lunatic with a mortar getting any ideas".

"The small boats are in danger. The small boats will anchor either here or tie on to us."

The Serb-led army and navy have blockaded Dubrovnik for four weeks and food, water and medicine are running low.

The siege has become a focus of the conflict that began when Croatia declared independence from Yugoslavia on 25 June and its Serb minority staged an armed uprising.

Croatian leaders estimate that anything between 1,000 and 5,000 people have been killed in the fighting.

President Mesic was welcomed fervently by the Mayor of Dubrovnik and other city dignitaries. But they will certainly want to know who is in charge of the Croatian defence forces and why European support for Dubrovnik has failed to materialise.

The success of the convoy is a political triumph for Mr Mesic on the eve of another round of negotiations in The Hague.

There, Serbia has its back to the wall as the EC points an economic gun to its head. If Serbia does not agree to the EC peace plan, in line with the other five republics, then it faces severe sanctions. It has four days to decide...

The Evening Standard – 13-11-1991

... With the Adriatic city of Dubrovnik trapped in a mediaeval nightmare, Lord Carrington was flying to Yugoslavia today in a last desperate attempt to stop the inferno of violence engulfing the country.

... With the Adriatic city of Dubrovnik trapped in a mediaeval nightmare, Lord Carrington was flying to Yugoslavia today in a last desperate attempt to stop the inferno of violence engulfing the country.

The photograph accompanying this story was taken from the Hotel Argentina on the southern outskirts of Dubrovnik, as rockets were launched on the old harbour where a vessel belonging to monitors of the European Union was the prime target. The once luxurious Hotel Argentina provided many journalists with simple and spartan facilities and an excellent view of the city during the weeks when JNA bombardments of the surrounding suburbs and of the old port itself were commonplace. Although the hotel was only a few hundred metres or so from the JNA hill-top gun positions and about one hundred metres from the Croat/JNA front line, it lay relatively safely just out of sight on the sea-front cliffs.

What many journalists did not find in Dubrovnik was the widespread and deliberate destruction of the city as described by Croat propagandists. Certainly there was widespread destruction of houses in the suburbs and some collateral damage within the old city, but it was evident that the JNA had no intention of destroying a World Heritage site, as they easily could have done, when they hoped to acquire the lucrative tourist trap for themselves. However, Croat nationalists, well-schooled during World War ll in the fine art of propaganda, elaborately listed even the smallest damage to a few roof-tiles and played up every opportunity to demonise their enemy by greatly exaggerating the extent of the damage to Dubrovnik. Meanwhile nothing was said of their own wholesale destruction of Muslim historic monuments in Bosnia-Hercegovina!

Sixty thousand people from the couple of kilometres around the city walls – or those of them who survived the bombardment of the last five days – have streamed terrified into the beautiful and romantic city centre.

Fishermen, chambermaids, shop-keepers, teachers and a huge population of the retired and elderly have joined hundreds of children in cellars and wine vaults, crammed into an area capable of housing less than one-twentieth of that number.

The winding leafy suburbs and ancient town houses will be deserted as the Croatian Guard attempt, as they always planned they would, to offer a last ditch defence about 100 yards outside the city walls.

Inside the walls, shortages of water, the risk of disease, the distribution of what food remains and preparations for treating casualties will be uppermost in everyone's mind.

Even last week there was concern that there were not enough medical supplies – and that was when there was still access to the hospitals which are now outside the reachable zone.

Hygiene will present problems. Soap and shampoo don't work in sea water and even a week ago at the Thanksgiving Mass for the arrival of the Human Rights Convoy, at a time when people could still strip and wash on the sea-shore, there was a distinct smell of unwashed bodies and the frequent discreet scratching of heads.

Hygiene will present problems. Soap and shampoo don't work in sea water and even a week ago at the Thanksgiving Mass for the arrival of the Human Rights Convoy, at a time when people could still strip and wash on the sea-shore, there was a distinct smell of unwashed bodies and the frequent discreet scratching of heads.

Over the past weeks, thousands of dispossessed refugees from towns and villages up and down the coast have trickled into Dubrovnik with barbaric tales of looting, pillage, mindless destruction and the inevitable burning of anything that fell in the path of the Serbian-controlled federal army.

Fresh water is everything. Epidemics were predicted several weeks ago but, despite urgent requests, no portable water purification or desalination plant had been brought into the city on the last ferry to visit Dubrovnik.

Several young mothers who were unable to breast-feed their babies and could not trust the water to mix with milk powder were evacuated last week but other new-born babies are known to be trapped within the city walls and in the western suburbs.

The public swimming pool, surrounded by plastic sheeting to catch spasmodic rainfall, has been the only public source of drinking water. But the pool is outside the city walls.

Many in Dubrovnik have made discreet plans for escape. Small fishing boats and the luxury yachts of German owners, already loaded with water and food, have been prepared for a last, desperate bid for survival.

But desperate it would be. The federal navy has already fired at small ships sailing further than one mile from the Dubrovnik coast.

Jadran Gamulan, the skipper of a 90ft yacht, said he would risk running for it to one of the many deserted islands, having already brought the vessel up the coast from Cavtat under federal army fire to the 'safety' of Dubrovnik.

But would he risk the life of his beautiful wife, Vesna, too? It was the only question he could not, or would not, answer as we drank wine (water is in short supply) and gazed up at the federal army flags on the hill-tops. Lord Carrington's mission is in response to calls from both sides for a peace-keeping force. But nobody is optimistic that it will have any more success than the EC peace efforts which preceded it.

Where are they now? This picture, taken at the time of the extraordinary events described above (November 1991), shows two Dubrovnik children who lived through a dramatic period in Croatia's history. On the right is the girl – referred to in this article – who became a faithful acolyte of the author and of Yugoslavia's then president, Stipe Mesic. As the war came to a close, Mesic became the first freely elected president of the newly recognised republic of Croatia. In 2011, twenty years after the events described above, the author hoped that one day he might hear from either or both of these 'children'!

Where are they now? This picture, taken at the time of the extraordinary events described above (November 1991), shows two Dubrovnik children who lived through a dramatic period in Croatia's history. On the right is the girl – referred to in this article – who became a faithful acolyte of the author and of Yugoslavia's then president, Stipe Mesic. As the war came to a close, Mesic became the first freely elected president of the newly recognised republic of Croatia. In 2011, twenty years after the events described above, the author hoped that one day he might hear from either or both of these 'children'!

© (1991) Christopher A. Long. Copyright, Syndication & All Rights Reserved Worldwide.

The text and graphical content of this and linked documents are the copyright of their author and or creator and site designer, Christopher Long, unless otherwise stated. No publication, reproduction or exploitation of this material may be made in any form prior to clear written agreement of terms with the author or his agents.