'Pat Line' – An Escape & Evasion Line

in France in World War ll

Its History, Personnel, Methods and Achievements

I

n the early 1970s the author was the first to explore the history and achievements of the Allied escape and evasion line, eventually known as 'Pat Line' which was based in Marseilles, operated throughout France during World War ll and in which several members of his family were intimately involved.

It was already known that many hundreds of escaping and evading Allied servicemen were smuggled out of occupied France from 1940-1944, but detailed information was then hard to come by. Most of the surviving members of the team were reluctant to talk or claim credit for their work, while most of the surviving British archive of SOE/MI9 documentation was still classified 'secret'.

However, a clearer picture eventually emerged thanks to accounts from many members of the RAF Escaping Society, from members of the author's own family, and from oblique references in numerous war memoirs where authors referred to their helpers while ignorant of the identity of the organisation that had helped them.

A brief summary of some of this information appeared in a press article Secret Papers in 1984. But by this time the author's mother, Helen Long (née Vlasto), had taken up the subject and in 1985 published the first definitive history of Pat Line in Safe Houses Are Dangerous. By the late 1990s the subject had attracted a number of escape & evasion enthusiasts, some of whom have made significant discoveries and greatly improved our knowledge of what was originally a very secret organisation.

By Christopher Long

Secret Papers (London Portrait Magazine, 1984)

See General Charles de Gaulle 1940-44

See Clandestine Warfare 1939-45

See Escapers, Evaders & Helpers TV Proposal

Escape Lines In Europe In WWll – RAFES 1994

See reactions to this page at Feedback

A Chronological History of Pat Line (1940-44)

1940

Garrow arrives in Marseilles...

Garrow

On 8th June 1940, while Allied Forces were recovering from their defeats in France and mainland Europe, culminating in the Dunkirk and evacuations, Ian Garrow (then a captain with the Glasgow Highlanders, part of the 51st Highland Division) arrived in Cherbourg for reasons still not fully explained.

France in June 1940 must have been a chaotic place, with German forces sweeping west across mainland Europe with astonishing speed. The Allied forces' evacuations from the beaches of Dunkirk saved thousands of men, but many others were captured.

Some of these men managed to escape, and yet others evaded capture and either went into hiding or began to try to make their way back to the UK.

The 51st Highland Division was left to fight on after the evacuation at Dunkirk, successfully distracting German attention away from the main force towards St Valéry-en-Caux until they were ordered to surrender on June 12th, when many thousands of troops were taken prisoner. In the case of the Seaforth Highlanders, their surrender was forced by French troops marching across their front carrying white flags and masking their guns.

The Highland Division comprised, among others, the Seaforth Highlanders, Cameron Highlanders, Gordon Highlanders, Argyll & Sutherland Highlanders and the Black Watch. This may perhaps explain why there are photographs of Garrow dressed in the uniform of the Seaforth Highlanders rather than Glasgow Highlanders (was Garrow seconded to the Seaforths from the Glasgow Highlanders?).

It seems probable that Garrow's battalion was connected with this action and tasked to work with the French 10th Army, and thus he must have been one of the last Allied soldiers fighting on French soil before the Normandy landings of June 1944.

The next we know is that some 7 or 8 days later (around 15-17 June) Garrow and the rest of the 140-strong Transport section became separated from the division near Mortagne in Normandy. Colonel Carnegie wrote to Garrow's parents in late June 1940 describing how this happened. Surrounded by German forces, Garrow and a Major McClure were among those who began to make for the coast at St Malo but again were overtaken by events (notably the German occupation of Normandy by 19 June and the signing of the French armistice 22 June).

Garrow and McClure seem to have decided to split into smaller groups and by around 25 July Garrow's group reached Tours in unoccupied France, where they surrendered to the French and were duly interned.

Capt. Garrow, Capt. Bradford, Sgt Wyatt and Fl. Off. Lewis Hodges were all at the Ile Jourdain camp by 1 October 1940 and transferred to Fort St Jean on 18 October 1940 where they were relatively free to come and go on parole. Capt. Frederick Fitch was Senior British Officer (SBO) at Fort St Jean and already appears to have been organising escapes via Spain. By this early date, Donald Darling was in Lisbon in order to assist the escape process from neutral territory. [See an excellent account of Captain B.C. Bradford's escapes in "Escape from Saint-Valéry-en-Caux by his son, Andrew Bradford.]

In Marseilles Garrow must have quickly met up with other members of the Transport section including Cpl W. West (Highland Light Infantry) who, with Capt. Fitch made a successful escape attempt across the Pyrenees in late December 1940 (possibly even with Garrow's help).

Many of the evaders and escapers from Dunkirk and St Valéry found their way down to Marseilles and the city must have been churning with Allied servicemen desperate to get back to the UK. Already in these early days escapes were being organised and Garrow rapidly seems to have become involved — certainly by the end of 1940.

An early figure in helping escapers was the Reverend Donald Caskie, who made his way to Marseilles after the fall of Paris in June 1940 where he had spent several years as Presbyterian Minister of the Scottish church. By mid-July, Caskie had re-opened the Seamen's Mission at 46 Rue de Forbin, a place which became well-known as a venue for Allied servicemen in need until he was ordered by the French to close it early in 1942.

Caskie also gave regular church services for the men interned at St Hippolyte gaol, taking the opportunity to smuggle in escape equipment. Eventually arrested in April 1942, he ended the war working for the Allies as officiating Chaplain to the Forces.

Presumably at an early stage it was realised that escapes would be difficult without local and civilian assistance. By the 14th February 1941 Garrow is recorded by Lt. Richard Broad, Seaforth Highlanders, as liaising between the prison and the consul (presumably American, though it is possible that it refers to Dr Rodocanachi) while several other useful civilians are providing help — many of them presumably introduced via the Rev. Caskie and his Seamen's Mission.

We will probably never know who recruited whom to help with escape activities, but many of the names which feature in Pat Line history begin to appear in witness accounts of the events of late 1940. For example, there is evidence that by mid December Garrow was working with Capt LA Wilkins, Capt Murchie, Harry Clayton and Tom Kenny.

1941

Garrow sets up his line...

Garrow

In mid February 1941 Murchie is remembered by Richard Broad and James Langley as acting "as their chief" and as working with Caskie until his own escape in April 1941 (when, according to Varian Fry, he "appointed Garrow as his successor"). It seems that Nancy Fiocca (née Wake), Louis Nouveau and Jimmy Langley all met Ian Garrow around this time, and that Elisabeth Haden-Guest (later Furse) first consulted Dr Rodocanachi with her sick son Anthony, although he seems to have been involved with Caskie and Garrow considerably earlier.

Haden-Guest seems to have convinced Rodocananchi to allow his apartment, at 21 rue Roux de Brignoles (close to the Gestapo headquarters), to be used as a safe house, which he did from June 1941 until his arrest in February 1943, and indeed the apartment served as the headquarters of the escape line for a considerable period.

Dr George Rodocanachi could already be credited with the saving of hundreds of Jewish lives, providing the necessary urgently needed medical certificates to enable them to board the last remaining immigration ships bound for the USA. He also helped healthy escapers to obtain repatriation permission by coaching and preparing them before their appearance before the Medical Board on which he was one of the examining doctors until his replacement by a German doctor in August 1942.

Bruce Dowding (aka André Mason, an Australian executed in June 1943 at Dortmund) was "associating with the members of the escape organisation" by Christmas 1940. In February 1941 he seems to have been actively engaged in assisting the escape route and was a friend of Donald Caskie. He was responsible for taking prisoners towards the Spanish boarder by train, via Toulouse and Perpignan.

On the 8th January 1941 Allied servicemen from Fort St Jean were transferred to St Hippolyte. Presumably Garrow, Wilkins, Murchie and others chose this opportunity to go to ground in Marseilles — many probably at Caskie's Seamen's Mission, although Murchie at least is known to have had a separate flat. Murchie apparently had frequent meetings with Allied servicemen there and many reported him as having organised their escape.

Meanwhile London had been interested in Garrow's progress ever since 18th June 1940 and, by the 19th Jan 1941, appeared uncommonly informed about his situation and to have some form of contact with him. Was Fitch's earlier escape planned so that he and Darling could establish communication and plan larger scale escaping and did Garrow take over the role of chief escape co-ordinator?

Certainly, Jimmy Langley claims that by the end of January 1941 Garrow has "established contact" with Barcelona and Madrid. This is also the time when London first hinted to Garrow's father that they are in contact with him. It seems clear that London continued to maintain secret wireless contact with those working with the escape line, at great personal risk to the wireless operators.

In 1942, two such wireless operators were Jean Nitelet, the one-eyed man known as Jean le Nerveu ('Jean the Restless'), and Tom Groome. Tom was aged 20, an Australian with a French mother. He was captured in early 1943 but managed to send a warning to London before throwing himself from a window. His runner, a young French girl called Edith Reddé, was able to escape and spent time in hiding in the Martin house at Endoume, near Marseilles. William Sparks, who was there at the same time, says in The Cockleshell Heroes, " We were also joined [February 1943] by Edit[h], who had been working with a British radio operator when they were both captured by the Gestapo and taken away to be interrogated. Upon arriving at Gestapo headquarters, the Britisher made a dive for the window, plunging to the street below. Edit[h] had no idea if he had survived the fall or not, but when all the Germans raced out to get him, she quickly followed them and slipped away. She now hoped to escape to Britain to join up with the Free French."

By 7th March 1941 Louis Nouveau's son Jean-Pierre succesfully escaped across the Pyrenees, at which point Garrow seems to have recruited Nouveau into the organisation. It appears he had already been helping Garrow financially for some time without knowing about the escape organisation. The Nouveau flat was used as a safe house for over a year from May 1941, offering shelter to over 150 escapers and evaders. As an example of how tightly security was maintained, Nouveau did not know until much later that the Rodocanahi flat was also used as a safe house, although Nouveau was a long-standing and close friend of the family.

A week later Garrow is reported as being in Perpignan, presumably assessing routes, guides and communications. Eventually the mountain routes with guides were found to be best, allowing escapers and evaders to make their way to neutral Spain. Once in Spain most men spent a period of time in the Miranda del Ebro internment camp.

At some point in 1941 Garrow went into hiding at the apartment of Fanny and George Rodocanachi, used as a safe house for escapers and evaders until George's arrest in February 1943. Soon after the end of the war Fanny recalled this to have happened in July, but Pat O'Leary, writing in 1985, remembered Garrow as having been at the apartment 'several months' before he himself took the same move in August 1941.

By mid 1941 there was a firmly established escape line, guiding escapers and evaders from northern France to the safety of Spain.

In Marseilles, the Rodocanachi and Nouveau flats were the most important of the safe houses, but escapers and evaders were also hidden by the Martin family of Endoume and Olga Baudot de Rouville, who was known as Thérése Martin, as well as, occasionally, Jean Fourcade.

Of the Martin family, William Sparks, in The Last of the Cockleshell Heroes, says "[February 1943] Our escorts led us to a high block of flats, where we caught the lift. We arrived at the top floor, and approached a door. One of the men knocked and the door was opened by a slim, dark woman. We were introduced: her name was Madame Martin. Inside we met her two little daughters, one aged about eleven and the other seven. Her husband worked at the docks: we would meet him that evening when he came home... Monsieur and Madame Martin were lovely people, doing all they could to make us comfortable. Their younger girl took a shine to me and decided to try and teach me French, mainly because she thought my pathetic attempts were hilarious. She would carefully shape her mouth to show me how to pronounce a word, getting me to copy her. But each time she'd roll up with laughter as I came out with the wrong sounds, and that set the others off laughing too. I knew she was sending me up but she was adorable. The girls must have been experienced in the task of assisting escapees for they never spoke a word at school about it: to do so would have been our undoing, as well as well as their parents'.. It became quite crowded in the flat, but there were plenty of beds or mattresses for us all to sleep on, and no-one went hungry. Sometimes friends arrived with a whole sheep, which they dumped in the bath and cut up."

Of Olga Baudot de Rouville, Louis Nouveau, in Des Capitaines Par Milliers, says " Jean de la Olla had sent us from the north a woman who was completely 'blown' near Lille and who worked for us under the name Thérése Martin, in reality Miss Olga Baudot de Rouville. Pat rented a small flat near Jarret for her and, especially after we left Marseille, she hid several pilots in this flat. She was very dedicated but had an extraordinarily difficult character: for example, she forbade the pilots to smoke in case the smell gave them away during her absence."

The involvement of several prominent Marseilles Greeks (including the Rodocanachis) seems to have led the Germans to refer to the line as 'Acropolis' (O'Leary recalls having noticed a file with this name while he was temporarily under arrest in July 1941), but it is known to history as 'Pat Line'.

The reason for this is the two-year leadership of Belgian-born Albert-Marie Guérisse, known as Pat O'Leary, alias Adolphe or Joseph.

O'Leary had been evacuated from Dunkirk on the last day of May 1940, three days after the capitulation of the Belgian army. A year later, 26th April 1941, he was on an undercover mission to France on board HMS Fidelity. The capsizing of his motor launch led to his arrest by French coastguards and his imprisonment at St Hippolyte for the next two months.

The date on which Garrow and O'Leary first met is equally unclear, but Helen Long, in Safe Houses Are Dangerous, claims that the two men had a rendez-vous in June 1941, shortly before the latter's escape from St Hippolyte prison. Was this meeting to arrange the details of the escape plans?

We can only speculate as to how much control London assumed over the activities of Garrow and others: were they, for example, encouraged to 'spring' O'Leary from St Hippolyte? In any event, O'Leary was already at the Rodocanachi's apartment by 2nd July 1941, when London sent one of countless seemingly insignificant radio messages ("Adolphe doit rester") instructing or allowing him to stay in Marseilles and work with the escape line.

Throughout the summer and autumn 1941 both Garrow and O'Leary were based at the Rodocanachi's apartment, which also housed a constant stream of escapers and evaders, until Garrow's arrest in October, after which O'Leary took charge of the escape line.

Once arrested, Garrow was eventually tried and sentenced in May 1942 to ten years' imprisonment. His parents continued to receive occasional news of their son, including a letter from Nancy Fiocca (Wake) written in March 1942 describing her visit to Garrow in prison.

Garrow's capture coincided with a crisis for the escape line. In the autumn of 1941 various members of the line, including Garrow himself (as he descibed in a letter to Donald Darling written in 1965), became suspicious of the colleague they knew as Paul Cole, mainly for theft of funds intended for reimbursing helpers. Cole was in fact a traitor, later killed by the French police in Paris in January 1946, and can be held directly responsible for the betrayal of over a dozen of the key members of the line.

At the beginning of November 1941 Cole was confronted in the Rodocanachi apartment by O'Leary, Bruce Dowding and others but managed to escape. The priority then was to warn endangered line members in the north of the country, and Bruce Dowding was arrested while he was attempting this.

Cole notwithstanding, Pat Line continued throughout 1942 to enable Allied servicemen to find their way through France and eventually back to Britain, where they were welcomed as much for their morale-boosting effect as for the actual manpower they represented.

1942

Garrow heads for Marseilles...

Garrow

In November 1942 the Germans occupied all France, so Marseilles was no longer technically under Vichy France control. The resultant threat to Garrow, then imprisoned at Mauzac, of deportation to one of the concentration camps, seems to have prompted O'Leary to organise a daring but successful escape plan to rescue him. After the rescue, of which Garrow's father was informed by letter from London in December 1942, Garrow used his own escape line to Spain, reaching his native Scotland by mid February 1943.

1943

Garrow heads for Marseilles...

Garrow

1943 was the year which saw the disastrous collapse of the escape line, with most of the members arrested or forced to flee. Louis Nouveau and George Rodocanachi were both arrested in February 1943 and later sent to Buchenwald, where Dr Rodocanachi died in February 1944. Pat O'Leary was arrested in March and later sent to Dachau, but survived the war and died in 1989.

1944

Garrow heads for Marseilles...

Garrow

1945

Garrow heads for Marseilles...

Garrow

Conclusion

Garrow heads for Marseilles...

Garrow

Little or no mention has been made of many, if not the majority, of the escape line helpers: for example, the wireless operators and those men and women who worked further in the north of France, concealing escapers and evaders and providing them with food, clothing and false identity papers at enormous personal risk and in the full knowledge of the likely consequences of their highly probable discovery or betrayal.

Their story has not been told here, but they can assuredly be said to be heroes of almost unbelievable courage, risking death and worse for no personal or financial gain but merely doing what they believed to be right. How many of us, two or more generations on, could honestly say that in their position we could be counted on to act as honourably?

Bibliography

For a detailed and authoritative account of all events on the 'Pat Line', see: Safe Houses Are Dangerousby Helen Long (1st Ed. 1985, hardback, William Kimber & Co., UK; 2nd Ed. 1989, paperback, Abson Books, UK) Forward by: General Sir Albert-Marie Guérisse (aka. Pat O'Leary).

For a detailed and authoritative account of escape and evasion on several lines, including Pat, Comet, Burgundy and Shelburn, see: 'My Brother's Keeper – Aid Rendered To Allied Airmen In France During The Second World War' a thesis by Sherri Ottis for Mississippi College, Clinton, Mississippi (1999).

Soon after 1946, Fanny Rodocanachi wrote a private account of her husband's wartime work for Pat Line. Entitled simply 'Dr George Rodocanachi' it was not intended for publication. Forty years after her death in 1958, it seemed appropriate to publish it on this site.

See also 'General de Gaulle & The Free French, London 1942-43' by his aide-de-camp François Charles-Roux.

Recommended Reading on SOE/M19, etc

General

(N.B. For reasons of 'national security' few books published prior to the 1980s reveal much of significance in terms of an operational or clandestine nature.)

- Paul BrickhillThe Great Escape (Faber, 1946)

- Paul BrickhillReach For The Sky (Collins, 1954)

- Peter Calvocoressi et alTotal War (Harmondsworth, 1989)

- François Charles-RouxLondon 1942-43, de Gaulle & the Forces Françaises Libres (On this site 1984)

- A. CrawleyEscape From Germany (Collins, 1956)

- Cyril CunninghamBeaulieu: The Finishing School For Secret Agents (Leo Cooper, Pen & Sword, 1956)

- Donald Darling Secret Sunday (Kimber, 1975)

- Donald Darling Sunday At Large (Kimber, 1977)

- Ian DearEscape and Evasion: Prisoner of War Breakouts and the Routes to Safety in World War ll (Arms and Armour 1997)

- J. Dominy The Sergeant Escapers (Ian Allen, 1974)

- Sir B. Embry Mission Completed (Methuen, 1957)

- M. R. D. Foot Resistance (Paladin, 1979)

- M. R. D. Foot SOE (London, 1984)

- M. R. D. Foot Resistance (Paladin, 1978)

- S. E. Hanson Underground Out Of Holland (Ian Allen, 1977)

- S. Hawes and R. White Resistance in Europe, 1939-1945 (Harmondsworth, 1976)

- C. Clayton Hutton Official Secret (Max Parrish, 1960)

- J. M. Langley Fight Another Day (Collins, 1974)

- Christopher Long Charles de Gaulle 1940-44 – The Man Who Stood Alone (On this site)

- Leo Marks Between Silk and Cyanide: The Story of SOE's Code War (HarperCollins 1998)

- R. Pape Boldness Be My Friend (Pan)

- R. Pape Sequel To Boldness (Odhams, 1959)

- Pat Reid Colditz (Hodder & Stoughton, 1962)

- Pat Reid The Latter Days At Colditz (Pan, 1955)

- A. Richardson Wingless Victory – The Story of Sir Basil Embry's Escape from France in the Summer of 1940 (Odhams, 1950)

- D. Teare Evader (Air Data Publications, 1996)

- Eric Williams The Wooden Horse (Collins, 1949)

France

- R. Austin and R. Kedward Vichy France and the Resistance (Croom Helm, 1985)

- J.-P. Azema From Munich to the Liberation, 1938-1944 (Cambridge, 1984)

- R. Cobb French and Germans. Germans and French (Brandeis, New England, 1983)

- M. R. D. Foot SOE In France (HMSO, London, 1966)

- B. Gordon Collaboration in France During World War Two (Cornell University Press, 1980)

- H. R. Kedward Occupied France (Blackwell, 1985)

- H. R. Kedward Resistance in Vichy France (Oxford, 1978)

- R. O. Paxton Vichy France: Old Guard and New Order (Columbia University Press, 1972)

- J. Sweets Choices in Vichy France (Oxford, 1986)

Germany

- M. Balfour Withstanding Hitler (Routledge, 1988)

- I. Kershaw Popular Opinion and Political Dissent in the Third Reich (Oxford, 1983)

- D. Peukert Inside Nazi Germany (Harmondsworth 1989)

- Hirschfeld & Marsh Collaboration in France: Politics and Culture during the Occupation (Oxford, 1989).

- Higgonet, Margaret Randolph et al Behind the Lines: Gender and the Two World Wars (New Haven, 1987)

The Netherlands

- M. R. D. Foot, (ed) Holland at War Against Hitler (London, 1990).

- G. Hirschfeld Nazi Rule and Dutch Collaboration: The Netherlands Under German Occupation (Oxford, 1988).

Pat Line

The Rodocanachi/Caskie/Garrow/O'Leary/Dowding story has appeared in numerous books and biographies. Among these are:

- Vincent Brome The Way Back (Cassell)

- Donald Caskie The Tartan Pimpernel (Fontana & Oldbourne Press, 1960)

- Alan Cooper Free to Fight Again – RAF Escapes & Evasions 1940-45 (Airlife Publishing. William Kimber, 1988)

- Ian DearEscape and Evasion: Prisoner of War Breakouts and the Routes to Safety in World War ll (Arms and Armour 1997)

- Peter Dowding Bruce Dowding (Unpublished account – 1988) (On this site)

- M. R. D. Foot & J. M. Langley MI9 Escape & Evasion 1939-45 (Book Club)

- Elizabeth Furse Dream Weaver [Haydon-Guest] (Chapmans, 1993) references to these events

- Helen Long Safe Houses are Dangerous (1st Ed. hardback: William Kimber & Co, UK, 1985; 2nd Ed. paperback: Abson Books, UK, 1989)

- Bruce MarshallThe White Rabbit (Pan)

- Brendan Murphy Turncoat

- Airey NeaveThey Have Their Exits (Hodder & Stoughton, 1953)

- Airey NeaveLittle Cyclone (Hodder & Stoughton, 1954)

- Airey NeaveSaturday At MI9 (Hodder & Stoughton, 1969)

- Fanny Rodocanchi Dr George Rodocanachi (Unpublished account – c. 1946) (On this site)

- André Rougeyron Agents for Escape (Louisiana University Press)

- Gordon Young In Trust & Treason (Edward Hulton)

- Nancy Wake The White Mouse (Pan)

NOTES:

George & Fanny Rodocanachi

The building containing the Rodocanachi apartment and 'safe house' still stands near Boulevard du Docteur Rodocanachi, Marseilles, France. Forty years later it was a tax office. The street had long been known as Boulevard Rodocanachi because it stood on a portion of the city which had been Rodocanachi family property. After the war it was renamed specifically in the doctor's honour. His first interrogation in 1943 took place at Gestapo Headquarters at 425 Rue Paradis which stood at the junction with Boulevard Rodocanachi. A plaque on the building's facade today reads:

Remember / behind the walls of this building the Gestapo / between 1942 and 1944 / tortured hundreds of Resistants / those who did not die under torture / were deported to Nazi extermination camps / they did not all return from these / we never forget them, for they gave their lives / to preserve the honour of France.

A ward at the Hôtel Dieu hospital behind the Hôtel de Ville on the Vieux Port was named 'Dr Georges Rodocanachi'.

After some reluctance on her part, Fanny Rodocanachi (née Vlasto) was eventually persuaded by the War Office in London to accept the OBE (Civil Division). On behalf of her husband, she received Britain's Commendation for Brave Conduct, the highest honour that could be awarded to a foreign national for work of this kind.

On behalf of the President of the United States, Dwight D. Eisenhower formally expressed the gratitude of the American people to Georges Rodocanachi for 'gallant service in assisting the escape of Allied soldiers from the enemy'.

Fanny was uncomfortable in post-war, post-collaborationist France and settled at 16 Sussex Gardens, Westminster, London, to be close to her brother's family and with his help adopted British nationality.

SOE & MI9

SOE was a part of MI9 which had distant origins in a WWl organisation devoted to obtaining intelligence by interrogating German prisoners of war and debriefing British ex-prisoners of war.

In WWll MI9, along with MI6, was at the heart of Britain's clandestine war effort. Although intelligence-gathering from enemy POWs and British POWs or servicemen on the run continued – handled by MI9(a) and MI9(b) respectively – MI9's activities went far beyond this. Created on 23 December 1939, it was headed by Col. Norman Richard Crockatt DSO MC who, along with MI6, ran a secret army of agents, informers, saboteurs, radio operators, couriers and escape line organisers, etc., all operating behind enemy lines.

MI9 prepared and equipped 600,000 British servicemen (particularly airmen) at risk of falling into enemy hands and, by using ingenious coding systems, was even able to communicate with British prisoners of war in German camps. It maintained communications with agents abroad through messages hidden among normal BBC radio programmes and through the BBC's special coded 'personal' messages. Escape equipment was ingeniously hidden in around 1,642 special parcels sent to prisoner of war camps.

It was first based at the Metropole Hotel, Northumberland Avenue, London and then moved to a country house, Wilton Park, near Beaconsfield (Camp 20). MI9 spawned a large number of specialist units such as its Intelligence School (IS9) which handled all the training requirements of agents operating behind enemy lines, including escape & evasion, interrogation, escape planning, maps, codes, the distribution of escape & evasion equipment, etc. Agents customarily attended SOE's training school at Beaulieu in the New Forest [see: Beaulieu: Finishing School For Secret Agents by Cyril Cunningham, above], its parachute schools on Salisbury Plain and specialist survival training centres in Scotland. Under the inspired genius of Christopher Clayton 'Clutty' Hutton it developed gadgetry of all sorts for the use of agents, escapers and evaders, while also collaborating with a reluctant and obstructive MI6 (the Secret Intelligence Service), to train agents to establish escape lines throughout Europe.

Under the aegis of MI9, but later virtually autonomous, was SOE (the Special Operation's Executive, formerly MIR), founded in July 1940. SOE's prime duty was to fulfil Winston Churchill's command to 'Set Europe ablaze'. To this end SOE's 'F' (France) section was particularly concerned with causing confusion, disseminating disinformation, organising and synchronising sabotage and generally disrupting the facilities and communications of the occupying Axis powers. Importantly it made strenuous efforts to rally, co-ordinate, equip and train French Resistance groups to harrass the enemy during and after the 1944 'D-Day' invasion on France. Most of this work was done directly by SOE agents (e.g. Yeo-Thomas) and the cells they established throughout France.

Violette Szabo (shot at Ravensbruck), Peter Churchill and Odette Hallowes (Sansom) are only the best known of hundreds of such agents operating in France and throughout the world during 1940-45. However, the introduction of SOE agents and their all-important radio operators into France often led them into the same channels ('lines' or réseaux) which harboured and assisted Allied escapers and evaders.

These lines and their personnel were frequently adopted and used by SOE which found it was able to harness the facilities, skills and courage that these well-established volunteers could offer. As the war progressed, the value of the work done by escape lines such as 'Pat', 'Comet' (Comète), 'Burgundy' and 'Shelburne' was increasingly appreciated at SOE's Baker Street (London) headquarters – and not just for the numbers of men who were saved to fight again. In France, prior to the D-Day invasion of Europe, SOE agents based among these escape lines and safe houses were able to train and supply the pathetically small and often unreliable French Resistance groups such as those of the maquis.

SOE was initially regarded by MI6 as a competitive threat. But a month after its foundation, with a staff of only 140, it scored a major triumph when it rescued £1.25 million worth of industrial diamonds from under the noses of the Germans occupying Amsterdam. Soon SOE was granted independence and became answerable first to Hugh Dalton, the Minister of Economic Warfare and then to Lord Selborne (assisted for a time by Sir Charles Hambro).

SOE's own chief, for most of its significant work and until it was disbanded in 1946, was Major-General Colin Gubbins. Gubbins, a gifted leader, lost his elder son in an SOE operation at Anzio in February 1944. Gubbins brought R. H. Barry back into SOE as his Chief of Staff, responsible for all operations and sections covering the Americas, Scandinavia, North-West Europe, South-West Europe, South-East Europe and South-East Asia.

By the summer of 1944, at its height, SOE is estimated to have consisted of just under 10,000 men and 3,200 women. Some 5,000 of them (mostly men) were agents – either on, or awaiting, operations. The rest were headquarters and support staff. Significantly, however, SOE used large numbers of young women as highly effective agents behind enemy lines, most of them recruited from the FANY (First Aid Nursing Yeomanry) because, uniquely, they were permitted to carry arms.

A memorial plaque to those who served with the Special Operations Executive was unveiled at Beaulieu, Hampshire, by Major-General Sir Colin Gubbins, former head of SOE, on 27th April 1969. It reads:

'Remember before God the men and women of the European Resistance Movement who were secretly trained in Beaulieu to fight their lonely battle against Hitler's Germany and who before going into Nazi-occupied territory here found some measure of the peace for which they fought.'

Escapers, Evaders & Helpers

See notes made in 1983 and 1984 concerning Escapers & Evaders from information supplied by Elizabeth Harrison of the Royal Air Forces Escaping Society. In 1984 Christopher Long submitted a formal proposal, based on these notes and others, for a TV documentary about Escapers, Evaders and their Helpers in wartime Europe, 1940-45. The idea of marking the 40th Anniversary of the RAFES was not accepted, despite the fact that the escapers, evaders and helpers were already vanishing fast. Fifteen years later, in 2000, a number of TV documentaries on this and related subjects appeared, but by this time there were very few witnesses still alive to tell their tales.

See notes made in 1983 and 1984 concerning Escapers & Evaders from information supplied by Elizabeth Harrison of the Royal Air Forces Escaping Society. In 1984 Christopher Long submitted a formal proposal, based on these notes and others, for a TV documentary about Escapers, Evaders and their Helpers in wartime Europe, 1940-45. The idea of marking the 40th Anniversary of the RAFES was not accepted, despite the fact that the escapers, evaders and helpers were already vanishing fast. Fifteen years later, in 2000, a number of TV documentaries on this and related subjects appeared, but by this time there were very few witnesses still alive to tell their tales.

In a statement, the Royal Air Forces Escaping Society says:

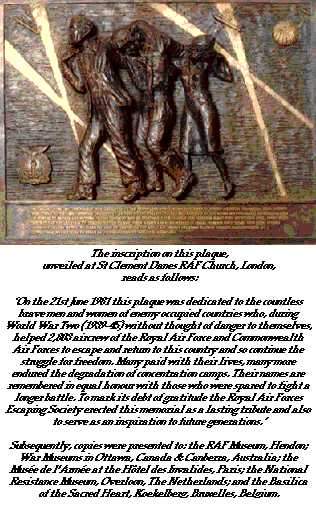

"... 2,803 members of the Royal and Commonwealth Air Forces aircrew who were shot down during WWII managed either to escape from captivity or, in the majority of cases, to evade capture. In many cases their eventual return to Allied territory was by clandestine means.

In escaping or evading they forced the enemy to devote scarce resources to stopping them. They also gave heart to the Allied Forces operating over enemy territory – aircrew knew it was possible to get back.

MI9 was set up to provide training in escape and evasion, co-ordinate escape lines and provide and devise materials – such as escape kits – to help valuable aircrew to get back.

Escapers and evaders were almost always reliant on the goodwill of ordinary people – extraordinarily brave people – in the countries under Fascist control. These helpers risked torture and death for the help they gave and their families faced deportation to concentration camps. Many thousands suffered because they aided Allied aircrew.

A number of organisations operated to guide and shelter evaders and escapers on their journeys to freedom, the best known of which were the Pat O'Leary Line from the North of France to Marseilles and the Comète Line from Belgium to the Pyrenees..."

Clandestine Activity

It's important to distinguish between five broad categories of clandestine activity in France during World War ll:

The Escape & Evasion lines

These grew spontaneously to assist Allied servicemen and agents who had escaped from German arrest, prisons and camps or who were evading capture. These lines were usually founded by civilians in France (les passeurs) and then adopted and supported by MI9. They included: 'Pat', 'Comet', 'Shelburne', 'Burgundy', etc. and were normally led by trained MI9 officers, couriers, radio operators, etc.

Their instructions came from London via the very vulnerable WT operators attached to each agent and often via coded messages in BBC radio transmissions and in the BBC's 'personal messages' – e.g. the 'Adolphe doit rester' message (received around 2-4 July 1941) indicating to Pat O'Leary that he should stay to develop the Acropolis [Pat] line. [I'm grateful to Keith Janes for identifying the origin of the 'Adolphe' code-name: Adolphe Lecomte was the name O'Leary had on the false identity card made for him in St Hippolyte just before his escape]

The first intelligence officer sent to develop such freelance lines was Donald Darling, an MI6 officer 'loaned' to MI9 and based in Portugal (a ploy by MI6 which regarded the later as a threat to its own operations.

The Special Operations Executive (SOE)

This was Britain's secret professional army of thousands of agents and saboteurs, operating world-wide in all theatres of the war. In France they were dropped behind enemy lines to disrupt and damage Germany's war effort and to supply, train and co-ordinate local resistance groups. Communications with London relied on WT radio operators, couriers and the coded 'personal messages' broadcast by the BBC.

SOE ran its own escape lines for its agents, parallel to those used by escaping and evading servicemen. These operations sometimes overlapped. SOE was at the heart of the 'code war' which is described in fascinating detail by the organisations code-master, Leo Marks, in Between Silk And Cyanide. Marks claims that he intercepted and decoded signals traffic between the Forces Françaises Libres in London and its agents in France.

The Secret Intelligence Service (MI6/SIS)

This was only the best known of several British intelligence-gathering services, largely reliant (as it still is) on British deep-cover agents, the interception and decoding of enemy signals ['sigint'], and the running of agents/informers who had been 'turned' within enemy organisations ['humint']. MI6 (also known as SIS or 'C') resented and distrusted SOE which it regarded as a threat to its own interests. It made strenuous and often devious efforts to curtail SOE's existance and hamper its operations.

Other Clandestine Operations

Some were run by conventional Armed Services which sometimes worked in collaboration with any or all of the other categories. The most important necessarily involved other intelligence organisations such as the Government Code and Cypher School, at Bletchley Park (known as BP or Station X) which continuously intercepted and attempted to code-break German signals traffic – notably 'Ultra' traffic on Enigma machines (see Alexis Vlasto who led the team breaking Japanese ciphers at Bletchley Park)

It should also be noted that a number of other secret services operated within Britain. In addition to the well-known MI5, were organisations whose identities and activities are still obscure. They were largely responsible for the vetting and surveillance of British and Allied personnel. Their routine attentions extended as far as cabinet ministers, military leaders, senior industrialists, newspaper proprietors and editors – indeed anyone in a position of power or influence who, had they been working against British interests, might have hindered or damaged British war aims. They probably also monitored their sister organisations such as SOE, MI5, MI6, MI8, MI9, etc., as well as foreign and Allied diplomatic missions in London.

Some of these groups may have had tangential links with overseas operations from time to time. Also monitoring signals traffic were the Air Ministry/RAF's 'Y' organisation, its Royal Navy equivalent and the Army's MI8. The GPO, the state-run monopoly which then operated all post, telephone and telegraphy services in the UK, was another key facility in clandestine signals interception. These functions are today the work of GCHQ, based at Cheltenham.

Equally, clandestine operations in France would never have been possible without special facilities provided by the RAF, Royal Navy and SBS who ferried individuals to and from enemy occupied territory.

The French Resistance (FFL)

This encompassed a wide range of partisan groups (often politically motivated) which sprang up spontaneously throughout France. The number of active résistants was in fact extraordinarily small (perhaps fewer than 1 in 10,000 of the total French population).

Unlike the SOE operations (above) the activities of these groups were to some extent monitored by the Forces Françaises Libres (FFL) which in 1940-43 was based at General de Gaulle's Headquarters in London.

French Attitudes to Allied War Activity

It was because the French résistants were so few and surrounded by so many collaborators and informers that their courage and sacrifice was so great. After the war, however, French governments actively colluded in propagating the myth that resistance was widespread. Consequently large numbers of very dubious 'résistants' suddenly emerged, were duly honoured and then allowed to occupy the highest positions in French society as presidents, cabinet ministers, heads of major institutions and senior industrialists, etc.

Sixty years after the war, the rôle of the French Escape & Evasion 'passeurs' was still studiously ignored in France – along with any mention of the parallel operations, efforts and sacrifices of MI9 and SOE personnel. Indeed the French are still encouraged to believe that the liberation of France was largely the result of the Résistance.

More ludicrous still is the widely held belief that General Leclerc and his 'French army' liberated Paris – an 'event' that is still officially celebrated each year! In fact French troops did not land in Normandy until August 1944 (at Ste-Mère-Eglise, more than two months after D-Day). However Britain and the USA invited Leclerc to march his forces into Paris at the head of the Allied armies as a diplomatic 'gesture' aimed at encouraging the French to accept de Gaulle as their national leader and the Leclerc army as a recognised authority. This gesture was important because while de Gaulle had been languishing in London (1940-43), later based in Dacca (Senegal) and in Algeria, he had, in his absence, been sentenced to death as a traitor by France's war-time 'Vichy' government.

The subsequent 're-writing' of French history was regarded by de Gaulle as a political necessity in order to inject national pride and unity into a deeply demoralised and divided nation. There were considerable fears that civil war might break out in France in the immediate post-war years. But ignorance of the contributions of the French passeurs is shameful. So is the lack of recognition of Britain's SOE and MI9 contributions. There can surely be no excuse for the fact that 60 years after the Liberation of France, French school children were still being taught a very distorted version of their country's wartime history and that film and television productions colluded in the sanitisation process. According to this re-interpreted version of events, France liberated itself, with a little help from its allies, after the people of France had generally resisted the occupation of their country. Conveniently forgotten is the fact that, of all the countries occupied by the Germany, France was the most assiduous in actively implementing Nazi ideology (e.g. the deporting Jews to death camps). And it was French authorities, supported by the vast majority of the French population, who were responsible for the deportation, torture and death of anyone who opposed French government policy in 1940-44. So, it was paradoxical and particularly sad that the British needed to install their own RAFES plaque in the Palais des Invalides in Paris in order that the heroism of genuine French 'passeurs' might be recognised in their own country by their own people.

Further Information Sources

An excellent source of information on (and from) Allied airman who passed through the escape lines is The Royal Air Forces Escaping Society (RAFES), 206 Brompton Road, London SW3 (+44 207 584 5378). The day-to-day work of this admirable organisation was largely wound up in 1995 when its mission to recognise and support the civilian 'passeurs', or helpers, was deemed to be completed. Another prime source on this and all World War l & ll subjects is The Imperial War Museum (Written Archives), Lambeth Road, London SE1 (+44 207 416 5000). See also Colditz Castle for information on the infamous prison's past and present.

In 1983 Elizabeth Harrison of The RAF Escaping Society in London said: "Altogether 2,803 (of whom only 50 managed to escape from German prison camps) were so helped by about 14,000 Allied civilians in nine countries. Of these helpers, 5,000 are [were in 1983] still alive."

Many of the SOE papers referred to in the article above are now held by me and destined for the Imperial War Museum, though some were passed to Capt. Ian Garrow's son, Alistair Garrow, in 1984. Many MI9 documents are at the Imperial War Museum, held under: WO208/Directorate of Military Intelligence.

Donald Caskie died on 27-12-1983 in Greenock, Scotland, and is buried at The Round Church, Islay. Among his descendants are Jenny & Ian and Nicole Johnston of Brisbane, Australia, to whom I'm indebted for photographs of Caskie and the Tartan Pimpernel press cutting.

'My Brother's Keeper' – Sherri Ottis

In 1998, post graduate historian and WWll Escape & Evasion specialist Sherri Ottis said she would appreciate contact from anyone with useful information on the 'Pat', 'Comet', 'Burgundy' 'Shelburne' or other 'lines', their participants and descendants. Her excellent thesis on the role played by helpers/passeurs on the escape and evasion lines was completed in 1999 published as a book under the title My Brother's Keeper in the USA in 2001.

In 1998, post graduate historian and WWll Escape & Evasion specialist Sherri Ottis said she would appreciate contact from anyone with useful information on the 'Pat', 'Comet', 'Burgundy' 'Shelburne' or other 'lines', their participants and descendants. Her excellent thesis on the role played by helpers/passeurs on the escape and evasion lines was completed in 1999 published as a book under the title My Brother's Keeper in the USA in 2001.

Sherri Ottis and Christopher Long exploring 'escape & evasion' territory in The Cevennes, France, in July 1999.

Bruce Dowding

In 1998 Peter Dowding sent me his account of Bruce Dowding, another of the founding members of the Pat O'Leary escape line who was executed by the Gestapo. He seeks further information.

Garrow & O'Leary on 'This Is Your Life' – 4 Nov 1963

Albert Guérisse (Pat O'Leary) was the subject on the BBC TV programme This Is Your Life, broadcast on 4 November 1963. Remarkably it was the first time he had seen Ian Garrow since Garrow's escape from France in 1942/43. As Garrow stepped onto the set as a surprise guest, Albert Guérisse was seen to mouth the words "I thought you were dead". This was hardly surprising. Ian Garrow's parents had invited Guérisse to visit them in Glasgow, Scotland, in 1945 (from where he was suddenly called away to identify the corpse of Paul Cole) and somehow contrived to lead Guérisse to believe that their son was dead. In fact Garrow was at that time either with the British forces in Berlin or staying in a nearby hotel at Montrose. The circumstances surrounding the Garrow family's sudden estrangement from their son on his return from France remains a mystery. Garrow might have been expected to be a troubled soul after his wartime experiences and his father, a doctor, might have been expected to understand this. Whatever the circumstances, the rift was never healed. (See the secret Garrow/MI9/SOE correspondence).

'Conscript Heroes' – Keith Janes

For the following notes I'm grateful to Keith Janes who has made a speciality of the history of Pat Line (through which his father escaped to freedom) and who has written an authoratative account of the line as experienced by his father. The book is yet to be published.

- 25-07-1940 – Garrow, Macdonald and McLaren surrendered to a French officer at Loches (near Tours) in 'free' France.

- 28-09-1940 – Garrow and 30 'other ranks' were Camp Ile Jourdain where they met Louis Hodges and Sgt. Wyatt.

- 18-10-1940 – Garrow and others were transferred to Fort St Jean in Marseilles.

- October/November 1940 – Parkinson is guided to Marseilles by a Welsh blacksmith from Lille (is this one of the earliest examples of an organised escape along the fledgling Pat Line?).

- December 1940 – Capt. L.A. Wilkins 'withdraws' from Fort St Jean to work with Garrow, Murchie and Tom Kenny (in the early days of the establishment of the escape organisation which became Pat Line).

- Pte J.W. Morris and Sgt Barson were two of the numerous Allied servicemen who were enabled to escape internment in France thanks to the inventive diagnoses of Dr Georges Rodocanachi. In both cases he found they had defective eyesight which assured them repatriation.

Feedback Subject: Secret Papers Date: 31-12-98 0:31am Received: 31-12-98 1:16am From: Webmaster, ppch@[nospam]interact.net.au To: Editor @ JTN, calong@dircon.co.uk "Christopher: The address: [Caskie] does not work – graphic is missing. I have just finished reading The Tartan Pimpernel and was after more information hence a visit to your site [Secret Papers]. Cris McGrath – Australia."

Secret Papers (London Portrait Magazine, 1984)

See General Charles de Gaulle 1940-44

See Clandestine Warfare 1939-45

See Escapers, Evaders & Helpers TV Proposal

Escape Lines In Europe In WWll – RAFES 1994

See reactions to this page at Feedback

© (1984-2002) Christopher A. Long. Copyright, Syndication & All Rights Reserved Worldwide.

The text and graphical content of this and linked documents are the copyright of their author and or creator and site designer, Christopher Long, unless otherwise stated. No publication, reproduction or exploitation of this material may be made in any form prior to clear written agreement of terms with the author or his agents.