Bosnia's Tide Of Human Misery

The Observer News Service 25-05-1992

From Christopher Long, in Split, the first foreign correspondent to visit the last vital Bosnian refugee escape route in Hercegovina.

N

ot since World War 11 has Europe seen a trail of terrified human misery on the scale of that now pouring out of the mountains and valleys of war-ravaged Bosnia-Hercegovina to the relative safety of Croatia.

An estimated 1.3 million refugees are on the move, a number that the UN High Commission for Refugees thinks could soon reach almost two million. They are mostly Muslim and almost exclusively women and children who now find themselves homeless, helpless and with little hope for the future – victims of what has now become the most vicious, ruthless and hate-fuelled war anyone can remember.

Thousands arrive daily to the sweltering heat of the harbour bus depot in the Mediterranean Croatian port of Split in battered buses – many riddled with machine-gun bullets – and disgorge their cargo of often dehydrated children and gaunt exhausted mothers who have already learnt to cover their mouths with their hands in a reflex action better known to relief workers in Ethiopia or Somalia.

But these people are not starving, not economic refugees. They are the normally successful teachers, civil servants, farmers or nurses that make up any south European community – people who only want to stop running and go home.

But how much longer they can continue to escape the intimidation of war in Bosnia-Hercegovina and the torching and looting of houses and whole villages is now in some doubt. After a long and often very dangerous detour north and then south through Hercegovina, the single escape route to Split from Sarajevo via the now devastated city of Mostar depends on a 15-mile stretch of mountain track. This road, leading out of northern Mostar, by-passes the now impassable main road and leads eventually to the Croat-Hercegovinan military headquarters at the small front-line town of Grude.

But how much longer they can continue to escape the intimidation of war in Bosnia-Hercegovina and the torching and looting of houses and whole villages is now in some doubt. After a long and often very dangerous detour north and then south through Hercegovina, the single escape route to Split from Sarajevo via the now devastated city of Mostar depends on a 15-mile stretch of mountain track. This road, leading out of northern Mostar, by-passes the now impassable main road and leads eventually to the Croat-Hercegovinan military headquarters at the small front-line town of Grude.

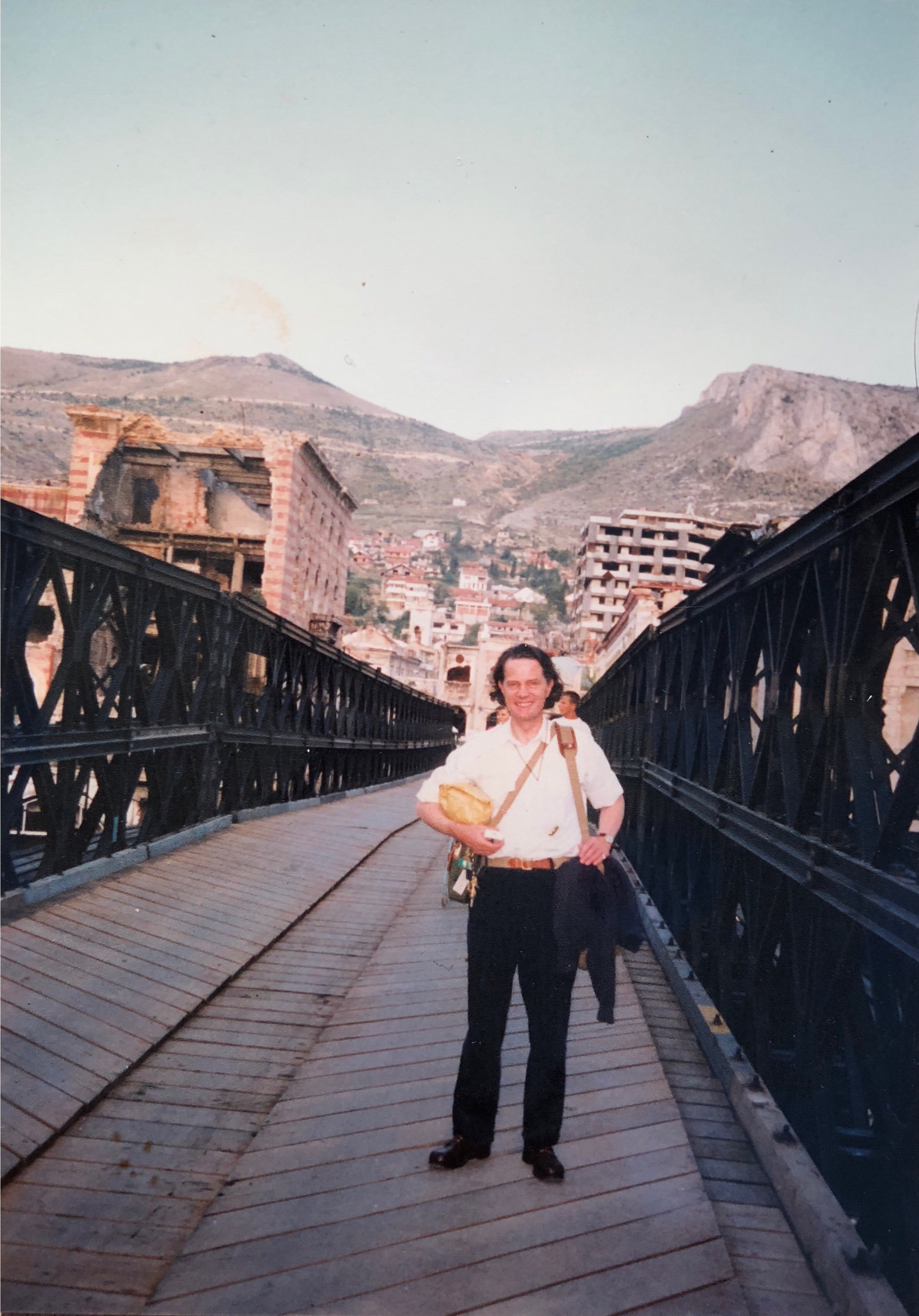

The author in Mostar in October 1994, two years after the events described in the article. In the background can be seen the almost total destruction of the city along the banks of the river Neretva.

At two or three points this road is fully within range of Serbian snipers and heavy machine-guns. It's this road which was taken by evacuating UN, EC and Red Cross officials from Sarajevo and Mostar. It is this road which receives regular air attacks despite being the only hope for the refugees. And it's this road which Col. Petkovic, operational commander of 7,000 HVO troops, is trying to keep open.

Speaking to him in his bunker beneath a hotel in Grude during the fifth air-alert before lunch, he told me he was optimistic of success in the long-run, despite having no air-cover. His men are armed with the same weaponry as his Serbian opponents, an enemy now led by his former brother-officer in the old JNA, General Panic – a man who Petkovic regards as a ruthless hardliner's hardliner. The EC monitors make valiant efforts to achieve temporary ceasefires for humanitarian purposes, but as their leader in Split, Dieter Waltman, admits, with no great confidence that many will be observed.

The majority of the victims of the insanity which has gripped Bosnia-Hercegovina are Europeans, often blonde-haired and blue-eyed, who converted to Islam under pressure from their Turkish rulers hundreds of years ago and who are now being 'cleansed' from their towns and villages as the Serbian minority of ex-Yugoslavia extends its greater Serbia plan – "Where there are Serbs, there is Serbia".

Sadly, by this week there were few if any official reception arrangements for the refugees flooding into Split. Three young Swiss women from the International Red Cross spend their time trying to arrange bulk consignments of food, drugs and other supplies from Western Europe, while Bayisa Wak-Waya of the UNHCR admits that he and his one colleague cannot begin to cope with the individual human needs of so many.

Sadly, by this week there were few if any official reception arrangements for the refugees flooding into Split. Three young Swiss women from the International Red Cross spend their time trying to arrange bulk consignments of food, drugs and other supplies from Western Europe, while Bayisa Wak-Waya of the UNHCR admits that he and his one colleague cannot begin to cope with the individual human needs of so many.

Local aid agencies such as Caritas (which reserves its help for Roman Catholics) are equally swamped by the sheer volume of people who have left and lost everything behind them.

Split, it is said, is full and so families find their own way to car ferries which drop consignments of refugees on islands such as Hvar, Brac and Korcula where the pressure of thousands of hungry, unemployed and unemployable people could well spark trouble before long among such small, intimate communities.

All along the coast near Split refugees fill the hotels so well known to tourists – refugees relieved to be safe, heart-broken to be homeless and hopeless, and mildly alarmed by the increasingly visible spectre of Croat nationalist extremism. The cohorts of intolerant Croatian HOS 'Rambos', the sinister black uniforms of freelance paramilitary fascists and walls daubed with Swastikas and Deutchland Uber Alles are unforgiving and ominous signs for those Muslims whose presence in increasing tens of thousands may one day be resented by their Croatian 'hosts'.

Zenaida, aged 16, is typical of thousands. She arrived in Split on April 24 from her home town of Donovac in Bosnia-Hercegovina, after a hair-raising 24-hour journey in which the bus ahead of hers was shot up by Serbian snipers and machine-guns. In Split she was immediately sent – with her mother, brother, sister and grandmother – to one of the two large city sports stadiums where she has lived for four weeks with dozens of other families in a squash court.

Zenaida, aged 16, is typical of thousands. She arrived in Split on April 24 from her home town of Donovac in Bosnia-Hercegovina, after a hair-raising 24-hour journey in which the bus ahead of hers was shot up by Serbian snipers and machine-guns. In Split she was immediately sent – with her mother, brother, sister and grandmother – to one of the two large city sports stadiums where she has lived for four weeks with dozens of other families in a squash court.

The food is monotonous but adequate. The lavatories and washing facilities are quite inadequate for the unexpected thousands who sleep cheek-by-jowl amid screaming babies and quietly weeping grandmothers. Her father, an illegal worker in Germany, cannot come to the aid of his family without being called up to fight – which would help no-one, she says. No-one from the aid agencies has visited them in four weeks or asked them what they need, or told them when or where they will go next.

At the plush Hotel Split, a semi-permanent home to more than 1,000 refugees, two little girls arrived at reception. Hana Kafedzic, 12, and her sister Nadija, 15, said they had no money, no food, no water and knew no-one. They had arrived the night before on a Children's Embassy bus from Sarajevo, evacuated by their father, a mathematics professor, who stayed behind. Their mother was trapped abroad and they had walked four miles to the hotel.

The hotel at first refused them baths, food or any assistance because "they haven't got the proper documentation" – until furious foreign journalists shamed the manager [Tonci Pejkovic] into action, demanding to know how a 12 year-old was supposed to know how to jump the hoops of bureaucracy after two sleepless nights, a machine-gun attack on their convoy and no idea whether their father and the rest of their family were alive or dead. Did he have children of his own, the journalists asked. How would he react if a hotel in London or Paris had turned them out onto the streets at night, homeless, unfed and unprotected. Clearly shocked, the manager instructed staff that these girls at least were taken in while the journalists themselves adopted them, making arrangements to escort them to safety.

The hotel at first refused them baths, food or any assistance because "they haven't got the proper documentation" – until furious foreign journalists shamed the manager [Tonci Pejkovic] into action, demanding to know how a 12 year-old was supposed to know how to jump the hoops of bureaucracy after two sleepless nights, a machine-gun attack on their convoy and no idea whether their father and the rest of their family were alive or dead. Did he have children of his own, the journalists asked. How would he react if a hotel in London or Paris had turned them out onto the streets at night, homeless, unfed and unprotected. Clearly shocked, the manager instructed staff that these girls at least were taken in while the journalists themselves adopted them, making arrangements to escort them to safety.

Hana and Nadija are now safely in the hands of friends in Rijeka. But they are among the lucky few. [Subsequently, after months in refugee camps and a year or more in limbo in Zagreb, the entire Kafedzic family was reunited and offered a home in New Zealand]

Today the UN, the Red Cross, the High Commission for Refugees and most journalists are targets for snipers and artillery throughout most of Bosnia-Hercegovina. The whole region is in the grip of anarchic insanity on a scale which needs to be seen to be believed. Sadly there are now very few people who dare to go and see and the Balkan tragedy will continue to unfold – perhaps spreading further south – with few to witness its appalling reality.

Pictured left: is the author and Hana Kafedzic on a ferry heading north from Split to Rijeka in May 1992.

Pictured left: is the author and Hana Kafedzic on a ferry heading north from Split to Rijeka in May 1992.

Much of the Dalmatian coast surrounding the port of Zadar was then in the hands of JNA/Serb forces which put ferries at risk and required shipping to make wide detours to avoid coastal batteries and possible air attacks.

Hana and Nadija were safely handed over to an elderly couple in Rijeka before spending months in a refugee camp in Croatia. But they were among the lucky few who were able to escape the appalling conditions in Sarajevo during the siege.

The large Kafedzic family, like thousands of others, escaped Sarajevo in ones and twos and eventually found themselves scattered throughout Europe.

The large Kafedzic family, like thousands of others, escaped Sarajevo in ones and twos and eventually found themselves scattered throughout Europe.

After meeting the author in Split and travelling together to Rijeka, Hana (12) and Nadja (15) spent months alone in refugee camps in Croatia. Some weeks later the author took a train to Smethwick, near Birmingham, to meet, interview but mostly to reassure their mother Fatima who was then staying there in a refugee centre for women.

In October 1992 he was based in Zagreb while making front line tours in and around Sarajevo. It was in Zagreb that he frequently met Fatima, Nadja, Hana and their 17 year-old sister Ekrima.

Eventually, following the relentless efforts of their elder sister, Atka (greatly helped by her war-photographer husband Andrew), the entire family was slowly reunited and offered a home in New Zealand. Each of them reacted to the traumas of the Bosnian war in their own way – none of them easy.

Left: The Kafedzic family on the day they were granted New Zealand citizenship – five years after being scattered throughout Europe.

I have remained in contact with the Kafedzic family and particularly with Nadja, Ekrima, Hana and (since 2018) Romana.

I have remained in contact with the Kafedzic family and particularly with Nadja, Ekrima, Hana and (since 2018) Romana.

Left: Nadja Kafedzic with her son Luca.

In July 2009 I was happily reunited with Hana who visited me in France, 17 years after we had last met.

Newly married and accompanied by her husband James, Hana and I found it much easier than we had feared to re-live painful memories as she prepared a book, co-authored with her sister Atka Reid, on their family's Bosnian war experiences (see below).

Left: The author with Hana Kafedzic, reunited in July 2009 in Normandy. Between them is James Schofield, Hana's husband since their marriage in New Zealand in January 2009.

In 2016, Ekrima's son Alen came to stay with us in Normandy and kindly helped us re-paint our Bailey Bridge.

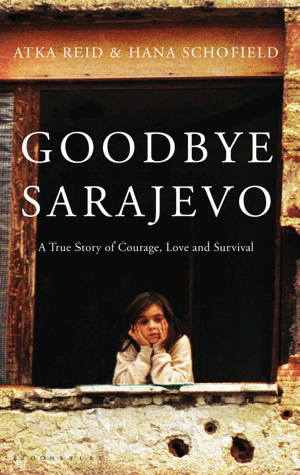

In May 2011, Hana Schofield and her sister Atka Reid published Goodbye Sararajevo (Bloomsbury Publishing), an excellent and touching personal account of the Balkan wars and in particular the consequences, for them and the rest of their large family, of the war in Bosnia. Their Goodbye Sarajevo web site says:

In May 2011, Hana Schofield and her sister Atka Reid published Goodbye Sararajevo (Bloomsbury Publishing), an excellent and touching personal account of the Balkan wars and in particular the consequences, for them and the rest of their large family, of the war in Bosnia. Their Goodbye Sarajevo web site says:

"May, 1992. Hana is twelve years old when she is put on one of the last UN evacuation buses fleeing the besieged city of Sarajevo. Her twenty-one-year-old sister, Atka staying behind to look after their five younger siblings, is there to say goodbye. Thinking that they will be apart for only a few weeks, they make a promise to each other to be brave.

But as the Bosnian war escalates and months go by without contact; their promise to each other becomes deeply significant. Hana is forced to cope as a refugee in Croatia, far away from home and family, while Atka battles for survival in a city where snipers, mortar attacks and desperate food shortages are a part of everyday life. Their mother, working for a humanitarian organisation, is unable to reach them and their father retreats inside himself, desperately shocked by what is happening to his city. In Sarajevo, death lurks in every corner and shakes the foundation of their existence. One day their beloved uncle is killed while queuing up for bread in the market square, in a massacre similar to the one three months earlier which prompted a cellist to make a lone protest in the deserted street. But when Atka finds work as a translator in an old smoky radio station, and then with Andrew, a photojournalist from New Zealand, life takes an unexpected turn, and the remarkable events that follow change her life, and those of her family forever.

Set in the middle of the bloodiest European conflict since the Second World War, Goodbye Sarajevo is a moving and compelling true story of courage, hope and extraordinary human kindness.

In November 2008 I was delighted to get the following message regarding the 16 year-old refugee, Zenaida/Zinaida/Zina, who appears in this article. I had not had news of her for 16 years and had no idea if or how she had survived the tragic war in former Yugoslavia.

"Christopher, I was with the U.S. IPTF (Police Task Force) in Bosnia 98-03. You wrote an article in 1992 including a refugee Zenaida... I thought you might like to know what happened to her as she shared with me how you were really concerned and had the respect of the refugees. 'Zina' is now in the Atlanta Georgia area working for me... now the manager of the business with a modest salary and bonuses, a beautiful daughter and, of all the bad she went through, she remembers those that care. After leaving Split the journey was still hard ahead for all of them. Thank you for being a reporter that cares. You should know that years later your impact of kindness may never be forgotten. I hope this mail finds you and in good health."

Despite months of warning from those of us on the ground (Nov 1991 – Feb 1992), Western governments were caught off-guard and quite unprepared for the human disaster which swept across Bosnia-Hercegovina in the Spring of 1992. As Serbs and Croats pushed west and east respectively, grabbing territory, destroying houses and villages and slaughtering or driving homeless refugees before them, only popular frustration persuaded European politicians to act as the irrational brutality spread unchecked. Their response was to send EC Monitors to 'observe and mediate where possible'. This policy only reassured the brutal militias that nothing need stop them in their plan to partition Bosnia along ethnic/nationalist lines.

Despite months of warning from those of us on the ground (Nov 1991 – Feb 1992), Western governments were caught off-guard and quite unprepared for the human disaster which swept across Bosnia-Hercegovina in the Spring of 1992. As Serbs and Croats pushed west and east respectively, grabbing territory, destroying houses and villages and slaughtering or driving homeless refugees before them, only popular frustration persuaded European politicians to act as the irrational brutality spread unchecked. Their response was to send EC Monitors to 'observe and mediate where possible'. This policy only reassured the brutal militias that nothing need stop them in their plan to partition Bosnia along ethnic/nationalist lines.

In 1996 The International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (The Hague) asked Christopher Long to supply prosecutors with a copy of his taped interview with Col. Petkovic. He was also asked to make a formal evidential statement. Ten years later Milivoj Petkovic appeared before the Tribunal to face nine counts of crimes against humanity, eight counts of violations of the laws or customs of war and eight counts of grave breaches of the Geneva Conventions. In May 2013 it was announced that Petkovic had been found guilty and sentenced to 20 years in prison.

The Road Out of Bosnia (The Daily Telegraph)

Bosnia's Girl Refugees (The Evening Standard)

© (1992) Christopher A. Long. Copyright, Syndication & All Rights Reserved Worldwide.

The text and graphical content of this and linked documents are the copyright of their author and or creator and site designer, Christopher Long, unless otherwise stated. No publication, reproduction or exploitation of this material may be made in any form prior to clear written agreement of terms with the author or his agents.