Bosnia's Aid Heroes

BBC Radio News – 23-07-1992

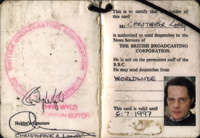

Filed to BBC Radio News, London, by Christopher Long in Split, Croatia.

A new breed of hero is emerging in this constantly evolving Balkan nightmare – the young, enthusiastic and idealistic aid workers. Mostly unemployed graduates from all over Europe, some are veterans of Romanian and Afghan convoys, many are endearingly innocent, but they've all descended on Split to make perilous journeys deep into Bosnia-Hercegovina in trucks and vans sporting the myriad logos of Europe's best-known and least-known aid agencies.

A new breed of hero is emerging in this constantly evolving Balkan nightmare – the young, enthusiastic and idealistic aid workers. Mostly unemployed graduates from all over Europe, some are veterans of Romanian and Afghan convoys, many are endearingly innocent, but they've all descended on Split to make perilous journeys deep into Bosnia-Hercegovina in trucks and vans sporting the myriad logos of Europe's best-known and least-known aid agencies.

Once it was we journalists who bored to death everyone around us with the litany of horror-spots we had worked in – Karlovac, Knin, Vukovar, Vinkovci, Osijek, Dubrovnik, Neum, Zadar and Sibernik. Today, as they constantly load and unload lorries that have travelled down from Paris or Geneva, via Rijeka and Pag Island on the Croatian coast, young doctors from Medecins Sans Frontieres and Medecins Du Monde swap a new litany of nightmare names in Bosnia with volunteers of Pharmaciens Du Monde and the young thrusters of Equilibre and Solidarite.

Where journalists swapped tales of wandering away from Croatian positions for a pee and being asked for an English cigarette by a Serbian militia-man, these young volunteers from UNICEF or the Muslim charity Mehamed swap stories of hair-raising experiences with broken drive-shafts in exposed territory or of meeting, head-on, an armoured personnel carrier 2,000 feet up on a single-track mountain road better designed for the day-to-day needs of a flock of goats.

Where journalists swapped tales of wandering away from Croatian positions for a pee and being asked for an English cigarette by a Serbian militia-man, these young volunteers from UNICEF or the Muslim charity Mehamed swap stories of hair-raising experiences with broken drive-shafts in exposed territory or of meeting, head-on, an armoured personnel carrier 2,000 feet up on a single-track mountain road better designed for the day-to-day needs of a flock of goats.

Just six weeks ago the heroes of Croatia were the tanned, combat-jacketted Croatian guardsmen on leave from the front and swaggering the streets of Split with their Kalashnikovs, earning universal adulation. In those days they held court at cafe tables near the bus terminal with tales of all the atrocities committed by the Serbs and the bloody revenge they would exact as soon as their battered buses delivered them back to Grude and on towards the awe-inspiringly beautiful mountains around Mostar, Cavtat, Neum and Sarajevo. There under the leadership of Mate Boban and Colonel Petkovic, they would soon be let loose alongside their Hercegovinan-Croat colleagues, to avenge the slaughter and atrocities for which the Bosnian Serb 'Chetniks' were alone, they claimed, responsible.

Today such warriors of the HVO are still up in the hills, doing their bloody work, but they seem to be losing their allure. They're harder to find in Split and the Dalmatian coastal resorts where the locals are increasingly peeved at the absence of any tourist trade at all – lamenting the loss of German sun-worshippers and their Deutchmarks – and increasingly resentful of the massive cost and consequences of housing, feeding and supporting almost one million, most Muslim, refugees who are now virtually the only visible evidence of the appalling war across the frontier. Just as Slovenia turned its back on Croatia when the war moved south into Croatia, so those Croats who are now spared the prospect of imminent attack are increasingly resentful of the consequences of the war to the south and east in Bosnia.

Today such warriors of the HVO are still up in the hills, doing their bloody work, but they seem to be losing their allure. They're harder to find in Split and the Dalmatian coastal resorts where the locals are increasingly peeved at the absence of any tourist trade at all – lamenting the loss of German sun-worshippers and their Deutchmarks – and increasingly resentful of the massive cost and consequences of housing, feeding and supporting almost one million, most Muslim, refugees who are now virtually the only visible evidence of the appalling war across the frontier. Just as Slovenia turned its back on Croatia when the war moved south into Croatia, so those Croats who are now spared the prospect of imminent attack are increasingly resentful of the consequences of the war to the south and east in Bosnia.

No such ennui troubles the young, eager and penniless aid agency volunteers. Though no substitute for German tourists and their Deutchmarks, the new warriors of peace fight for the sun-loungers while taking well-earned rests from loading medicines, food, baby milk, sanitary towels and disinfectants onto lorries that will, tomorrow, drive through the middle of the most lawless, anarchic, confused, inhumane and hate-filled war-zone that anyone here has ever witnessed.

Like the journalists, the EC Monitors and the Croat soldiers who came home from spells in the war-zones and occupied the very same sun-loungers before them, the aid workers too are developing a litany of horror-spots, returning each time with a little less bravado, a little more subdued, and not entirely sure whether to believe the evidence of their own eyes – the sight of devastated towns and villages, the bodies lying in the streets, the multiple rapes, the cold-blooded assassinations of young and old, the sheer, heartless, pointless cruelty of it all.

Again, like the journalists before them, the conversation is rife with rumour. Someone has heard that four or five thousand terrified Bosnian Muslim refugees have been turned back at the 'pink zone' Croatian border-point at Bosanski Brod by Danish UNPROFOR troops and that they are at an extreme point of desperation. Another is alarmed to hear reports that as much as 50 per cent of the UNHCR aid being flown into Sarajevo is reaching the black market within hours of it negotiating the treacherous Dobrinje gauntlet between the airport and the city centre. Someone else claims to have heard that UNHCR aid is turning up on street markets in Bulgaria. All such reports are, by their very nature, hard to confirm and not at all improbable.

And, less surprisingly, rivalry between the aid agencies is rife. The large organisations such as UNHCR, delivering up to 200 tons on 21 Hercules and C160 flights per day, regard the three or four tons delivered by Solidarite as a "comparatively insignificant" contribution, to quote Tony Land, the UNHCR coordinator from Zagreb.

And, less surprisingly, rivalry between the aid agencies is rife. The large organisations such as UNHCR, delivering up to 200 tons on 21 Hercules and C160 flights per day, regard the three or four tons delivered by Solidarite as a "comparatively insignificant" contribution, to quote Tony Land, the UNHCR coordinator from Zagreb.

The smaller agencies, on the other hand, say they deliver direct to the villages and towns where they know it's needed. Pierre de la Bretesche of Solidarite says: "We go out in our cars first, we establish the need, we load our lorries accordingly and then we arrive – we hope".

Interestingly, since I have drawn comparisons between the old armed warriors and the new aid workers, there's good reason to believe that this whole conflict will be seen to have been a freelancer's paradise. At all its stages it has been fought largely by freelancers, it has been recorded to a large degree by freelance photographers and reporters. Now, it seems, it is the freelance aid-worker who is bringing the most direct relief to victims of the Balkan conflicts.

Interestingly, since I have drawn comparisons between the old armed warriors and the new aid workers, there's good reason to believe that this whole conflict will be seen to have been a freelancer's paradise. At all its stages it has been fought largely by freelancers, it has been recorded to a large degree by freelance photographers and reporters. Now, it seems, it is the freelance aid-worker who is bringing the most direct relief to victims of the Balkan conflicts.

Filed from Split, Croatia, to BBC Radio News after several tours of central Bosnia and the Croat/Serb/Muslim front lines north of Mostar. Large waves of 'ethnically cleansed' refugees were continuing to flood across Hercegovina to safety on the Dalmatian coast. Since this was before the deployment of the UN, or any other peace-keeping forces, aid agencies, observers and reporters travelled across these anarchic and extremely dangerous zones entirely unprotected.

Filed from Split, Croatia, to BBC Radio News after several tours of central Bosnia and the Croat/Serb/Muslim front lines north of Mostar. Large waves of 'ethnically cleansed' refugees were continuing to flood across Hercegovina to safety on the Dalmatian coast. Since this was before the deployment of the UN, or any other peace-keeping forces, aid agencies, observers and reporters travelled across these anarchic and extremely dangerous zones entirely unprotected.

© (1992) Christopher Long. Copyright, Syndication & All Rights Reserved Worldwide.

The text and graphical content of this and linked documents are the copyright of their author and or creator and site designer, Christopher Long, unless otherwise stated. No publication, reproduction or exploitation of this material may be made in any form prior to clear written agreement of terms with the author or his agents.